“Never bring a knife to a gunfight.”

It’s a phrase you’ve heard before. Maybe you heard it used figuratively to mean “don’t come ill-equipped to a conflict.” Maybe you heard it used literally in action movies like The Untouchables or Glimmer Man. In each meaning, the implication is the same: he who lives by the sword shall be shot by those who have a gun.

What if that isn’t always the case though? What would it take - could it take anything - to bring a knife to a gunfight and win?

In 1983, Salt Lake City Police Lieutenant Dennis Tueller conducted experiments that would create ripples through the world of firearm self-defense and law enforcement training. He wanted to determine the reaction time of an officer drawing a gun and opening fire vs a fast-charging assailant. He selected volunteers to charge twenty-one feet, another group of volunteers to draw, aim, fire, and successfully hit a target (they weren’t aiming at the runners in case you were wondering). He timed the two groups against each other. The fastest runners and the fastest draws both hit their marks at 1.5 seconds.

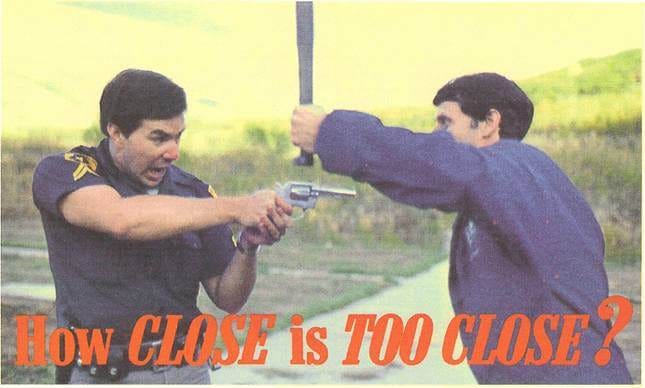

Lieutenant Tueller determined that twenty-one feet was the minimum distance needed to maintain for an officer to successfully draw and fire a charging attacker without them reaching the officer before a shot could be successfully fired. He published his findings in an article titled “How Close Is Too Close” in a 1983 issue of SWAT. Law enforcement agencies embraced the findings. Different departments developed their own version of a “Tueller Drill” to prepare officers for situations where their quick reflexes are needed in a knife attack. The principle was used in the court case Buchanan vs The City of San Jose to determine the police acted within acceptable force and has since been adopted by civilian self-defense circles.

Above: A very dramatic reenacment of the issue Lt. Tueller wrote about.

The Tueller Drill is imperfect. It calculates the reaction time of trained policemen with holsters developed for quickly drawing a weapon, but doesn’t account for the time taken to draw a concealed firearm. It doesn’t take into account the fact that, contrary to movie logic, people don’t always immediately drop when shot - especially if they’re hopped up on drugs and adrenaline. It works well as a way to sharpen a shooter’s draw speed and close the reactive gap between an oncoming attacker and opening fire.

What it doesn’t test - what it can never test - is if the can keep a clear head enough to draw their weapon in the 1.5 seconds needed to squeeze a few rounds off while being attacked. Even the pressure of a high-stress test rarely compares to the real experience of an armed encounter. Even trained cops sometimes flee under fire. Now imagine how an untrained civilian reacts.

Picture the scenario: you’re not militarily trained. You have one handgun. A man charges with a knife. He’s too close for you to draw and you know it. You can’t run. You can’t shoot.

But you also have a knife. En garde it is?

A mystic aura surrounds knife fighting due to the inherent skill involved. It also attracts an industry of bullshido artists preaching the best methods of knife self-defense. Alleged techniques on how to disarm a knife-wielding opponent by bending their wrists or round-kicking the blade from their hand work great in movieland. But they are more likely to result in your legs or arms being cut by even an amateur cuchillero, let alone an expert.

But if you have a knife as well? Many different knife fighting methods exist across the world, from the Sicilian Scherma de Stilleto to Filipino Armis, each with their own distinctive grips and footwork practices like fencing.

Above: Demonstration of knife fighting principles. Looks like it hurts.

Unlike fencing, the short length of even the longest knife blade forces you to lunge farther than with a sword, leaving more of your body vulnerable to attacks. A common way to parry a knife attack is to slash the arm or hand of the attacker. An experienced attacker might keep the underside of their wrist away from the direction of their opponent so that only the backside of their wrist or hand is slashed. Otherwise, you allow your arteries to be cut.

Needless to say, knife fights generally end with the winner in the hospital and the loser in the morgue. There are ways to beat back a knife attacker with a knife, but even an unarmed man, if he grabs hold of you, can potentially turn your own blade against you. Facing an experienced knife fighter is an excellent way to lose blood at best.

So keep all of this in mind when reading the case study of perhaps the most shockingly successful counter to the old warning about never bringing a knife to a gunfight - or for that matter, a knife to a knife fight.

GET THREE SEVEN COFFINS READY

The El Dorado County town of Placerville had only been a real town for five months when the three friends marched into the mountains. The mining settlement’s new God-fearing citizens were a change from the days when two Frenchmen and a Chilean were lynched for the crime of robbing a local gambler. Needless to say, the new churchgoers and temperance types demanded a name change from the town’s old moniker, “Hangtown.”

El Dorado County had undergone a transformation since its incorporation four years prior. It was the center of Gold Country, notorious for its unstable origins, though bloodless compared to the frequent violence of San Francisco and Los Angeles. But the presence of churches and residents more respectable than prospectors and gamblers didn’t remove the element of danger. Anyone wandering the back-country roads of the Sierra Nevada put themselves at potential risk. A year ago, the mountains were aflame with reports and rumors of a gang led by an enigmatic “Joaquin.” Who knew what else crouched between the pines?

Jonathan R. Davis walked the trail along the American River just north of Placerville on December 19th. The intervening years between his arrival to California and that cold winter Tuesday remain obscure, but by then he had followed his fellow 49ers down the path of prospecting for gold. Two fellow Southerners accompanied him: an Alabaman named James C. McDonald, and a Mississippian named Dr. Bolivar Sparks. Both men appeared to be well-acquainted enough to risk the cold together in order to locate gold in a nearby quartz vein before the gold was depleted.

Above: The American River near Ruck-A-Chucky Falls. Not far from where the shootout occurred.

They traveled light. They eschewed mounts, taking the road on foot. They carried only the tools and the bare-minimum supplies needed, but came prepared with revolvers and knives. They had good reason to take caution. Two days prior, six Chinese men had been robbed and murdered. The following day, four Americans (read: Anglos) had been similarly massacred.

The killers were a fourteen-man gang of multicultural marauders: four Mexicans, three French men, two white Americans (no, no turtle doves), and most prominently, five former members of the Sydney Ducks. Having escaped deportation and the wrath of vigilantes, the surviving Sydney Ducks found new followers and a new MO: hit-and-run robberies along the mountains where they could slip away with ease. If it was good enough for “Joaquin”, it was good enough for them.

Maybe they weren’t aware. Maybe they didn’t care. The three men marched towards the deep interior of the Sierra Nevada into Rocky Canyon, traveling along the river near Ruck-a-Chucky Falls, in defiance of the risks that winter weather and wild animals would pose.

Gunsels sprung from the bushes and fired. The first shot killed James McDonald before he had a moment to realize what was happening.

Davis and Dr. Sparks drew their weapons. They stood against the onslaught of bullets. Sparks fired twice before a bullet ripped through his gut and forced him to the ground, leaving Davis as the last defender.

Davis could have fled and left his companions. He didn’t. He could have found cover behind a tree. He didn’t.

He stood his ground like he was back in battle. He fired as rapidly as his two Colt Navies would allow. He fired one gun, then the other at the same target if he thought he missed. Enemy bullets tore through his clothes as he emptied his two guns into seven of the fourteen men.

Above: Jonathan R. Davis holding his own against his attackers. Credit to Bob Boze Bell and True West Magazine.

Both sides had exhausted their ammo. Through the haze of gun smoke, the bandits charged Davis with their blades. Davis had no time to grab James McDonald or Dr. Sparks’ loaded guns. He drew his own Bowie knife to meet the attackers as an equal. He stabbed one man to death. Another lunged at him. Davis knocked the blade from his hand and swiped his Bowie knife towards his face, severing his nose. Two remaining bandits approached. Both had been wounded in the previous raids. Both handled their blades poorly due to the lingering pain of their previous wounds and were swiftly disposed of.

The three surviving bandits didn’t bother to avenge their compatriots. They fled into the woods, leaving Davis standing among the bodies.

MY MISTAKE, FOUR ELEVEN COFFINS

The song of a gun travels far. Isaac Hart, P.S Robertson, and John Webster had been hunting for dinner for their mining camp when they found the sound of the nearby guns too close for comfort. The three miners ran down the hill to investigate.

From a distance, they saw a single man holding his own against fourteen. By the time they reached Jonathan R. Davis, he had torn fabric strips off his shirt and begun bandaging the wounded Dr. Sparks and four wounded bandits.

Dr. Sparks’ condition was poor. Three of the four wounded bandits were on the brink of death. The noseless bandit would survive if his wounds didn’t catch an infection.

Davis saw the three miners rush down the hill. He grabbed James McDonald’s fully loaded pistol. He aimed at the three men, ordered them to stop. Had he been less discriminating with who he fired on, he would have killed the primary witnesses of an unbelievable standoff.

The three men assured him they were friendly. They helped Davis bring Sparks and the bandits to their eighteen-man camp for rest and treatment. Treatment couldn’t save the worst wounded of the three assailants. The two bandits died that night.

The eighteen miners scoured the site of the shootout to pick the pockets of the dead. They recovered $491, four ounces of gold dust, seven gold watches, and two silver watches. The miners didn’t keep the loot long. Davis demanded the goods be handed to Dr. Sparks. The Doctor would need the money for his treatment. Worst case scenario, his family would need it if he passed. None of the miners were willing to fight Davis on the issue.

The noseless bandit felt grateful for being spared and treated by Davis. He confessed his and the gang’s involvement in the previous two homicides. He told the witnesses of the role the surviving Sydney Ducks played in the formation of the gang. According to a report by the Daily Alta California, he allegedly provided written evidence of by-laws for the gang. He didn’t have a chance to testify in court. On December 20th, his health nosedived and he passed away.

An inspection by the miners - mentioned in a letter by John Webster - revealed that Jonathan R. Davis’ clothes had been riddled with twenty-eight bullet holes, eleven through his coat, nineteen through his hat. But he only sustained two wounds that grazed his flesh. Given that there were fourteen bandits armed with six shooters and at least three of these bullets entered the bodies of his friends, that puts it in a total of eight-four shots fired by the gang, fifty-six of which did not riddle Davis’ clothes or any bodies with bullets. It’s a better shooting average than stormtroopers, but still pretty poor aim.

Above: Some obscure space opera from the seventies.

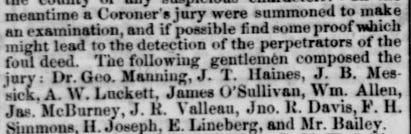

The miners formed an informal coroner jury, recording the statements from the few witnesses. They determined that Davis acted in self-defense, with each witness providing consistent statements that corroborated each other’s testimonies. They signed their report and sent it to Placerville with a miner named John E. Lyles. Webster concurrently wrote a letter to a “Wm. Henderson in Placerville that contained a report of the shootout. He had Lyles deliver the letter to Henderson, which would later be published in the Daily Alta California.

His condition still poor, Dr. Sparks was delivered to his home in Coloma by the remaining miners in order to receive adequate medical treatment. The best doctors couldn’t save the doctor. He died of his wounds on December 26th, 1854, three days after the story of the shootout hit the presses in Northern California.

TRUE DIES

It’s not without cause that “if it bleeds, it leads” is a well known axiom in American life. Turn on any local news report or read any news publication, and the screens and pages will likely be filled with blood. But extraordinary events especially make for excellent newspaper fodder. The news is a business in which every competitive outlet races to break a scoop or editorialize it first. Even reporting on a sensationalized story to call “bullshit” on it or to critique the reporting around it is better business than ignoring it altogether.

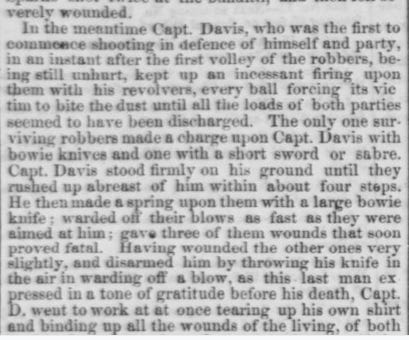

The Placerville Mountain Democrat boasts the claim of being the oldest continuously running newspaper in California. Formed from a merge between The Argus and The El Dorado Republican, the Mountain Democrat was still a relatively new paper only ten months in print when the Davis shootout occurred. The Mountain Democrat broke the story first in a December 23rd, 1854 extra edition. They published the report from the miners alongside Webster’s eyewitness letter to Henderson with the caveat that the story could be “slightly, very slightly, exaggerated, but not impossible.”

The news set Placerville and El Dorado County aflame with excitement. A local shootout was newsworthy enough. A one-man-against-many story was spectacular. The story spread to Sacramento and San Francisco and the Daily Alta California published the story the following day on Christmas Eve of 1854.

Above: A clipping from the Daily Alta California’s reporting of the event (Daily Alta California Issue 355, dated December 24th, 1854

Much of the appeal of the story lay in the improbability of a single man holding his own against fourteen attackers and eliminating all but three of them. The skeptics responded with the same promptness as the believers. Even then, tall tales were common enough for those with keen noses for the smell of bullshit to be on the guard for false reporting. The Sacramento Union derided the story as “bogus” and accused Davis of “Munchausenism.” The San Francisco-based Daily California Chronicle countered with the more generous, if questionable, suggestion that unusual events like a 14 vs 1 shootout was completely in character with the kind of state California was.

The Mountain Democrat was placed in the position of defending their journalistic credibility. For Davis, the skepticism surrounding the reports was far more personal. He had lost two friends and faced down death only to be derided as a liar. Even a seasoned veteran of war as he was doesn’t come out of losing two friends in an ambush mentally unscarred.

Jonathan R. Davis arrived at the offices of the Mountain Democrat in Placerville on December 27th. Perhaps the death of Dr. Sparks the day prior, combined with the skepticism of the press, compelled him to tell his truth. He confirmed the accounts with the editors of the Mountain Democrat. He described the events in a newspaper column. He maintained a degree of humility in his account by saying “I did only what hundreds of others might have done under similar circumstances, and attach no particular credit to myself for it.” He offered to take any who doubted the veracity of the reports to the site of the shootout where they could see the graves of the dead bandits themselves. No one accepted his offer.

Doubt around the circumstances of the shoot-out continued into the following year. A so-called Mr. Williams arrived in El Dorado County, a brother-in-law of Dr. Bolivar Sparks. Seeking information on the death of Dr. Sparks, he located the mining camp deep in the Sierra Nevada where Webster, Hart, and Robertson confirmed the veracity of the accounts he had only read in newspapers of his brother-in-law’s demise.

Disconnected from outside affairs and hoping to continue with their mining ambitions, the three men had been unaware of the controversy surrounding the shootout reports until visited by Williams. Believing the story behind his kinsman’s murder needed official confirmation, he convinced them to return to Placerville to explain their account before a judge.

March 20th, 1855. The three miners and Jonathan R. Davis stood in front of a delegation of Placerville residents. The county Judge R.M. Anderson oversaw the public hearing. Each man retold the events of the December 19th shootout between Davis and the gang. Questioning and cross-referencing the four remaining eyewitnesses, Judge Anderson found the accounts consistent. So too did the Placerville public. The Mountain Democrat published the testimonies and the Judge’s response as an informal exoneration of Jonathan Davis.

BUT WHAT IF WE’RE WRONG?

Was Jonathan R. Davis’ story - to use the Sacramento Union’s phrasing - bogus? Judge Anderson didn’t seem to think so. Neither did the Placerville public, or the San Francisco newspapers.

But people are often willing to believe extraordinary acts of heroics if, for no other reason, the comfort such an account of courage provides. Placerville’s residents were unlikely to disbelieve a story that could inspire others to stand firm against abuse from banditry. Newspapermen certainly wouldn’t want to dispel such a striking image as a lone man defending himself against impossible odds.

We’ll never really know the full truth. Three witnesses saw the middle of the fight. One was a participant. While Dr. Sparks and the noseless bandit confirmed the accounts, both died before they could testify in person to the public under the scrutiny of a judge. The consistency of each of the men’s accounts works in their favor, though there is always the possibility that the men conspired to set their fake stories straight.

But to what end? The miners had nothing to financially benefit from telling the story. Davis never acquired a bounty for killing the bandits. The possibility that they were the true aggressors crossed my mind while trying to compose alternatives to the record. But the bandits’ loot went entirely to Dr. Sparks, and then his widow after he passed. Covering a crime none of them benefited from seems unlikely.

The best argument in favor of the account comes down to the conduct of Jonathan R. Davis in the aftermath of the shootout. It wasn’t Davis who reported the story to the papers, but the miners. He defended himself in print, but did not turn himself into a local celebrity the way men like Harry Love did. There were no paid speaking tours to San Francisco, no books, no leveraging his fame to run for office.

In fact, there wasn’t much of anything from Jonathan R. Davis following the shootout. To this day, there is no officially confirmed date of his death. The rest of his life was lived quietly, fleeing from the fame that killing brings.

OLD GUNS

Riding into the sunset is the classic coda to a western movie. The protagonist redeems the innocent with the blood of the wicked, mounts up, and rides into the horizon like an avenging angel ascending to the Heavens. Never to be seen by the townsfolk again.

Reality tells a different story. The lives of famous old west lawmen continue, often with less glamor than the moments that gave their names fame. Pat Garrett and Harry Love both spent their remaining years struggling with financial setbacks before dying undignified deaths. Wyatt Earp chased financial booms with little success and spent his waning days advising silver-screen cowboys in Hollywood. Such is the reality of history: if you’re remembered at all, it’s often for a brief period of your life. Sometimes little more than a thirty second shootout will overshadow every other aspect of your existence until your name becomes reducible to the single act which you are remembered for.

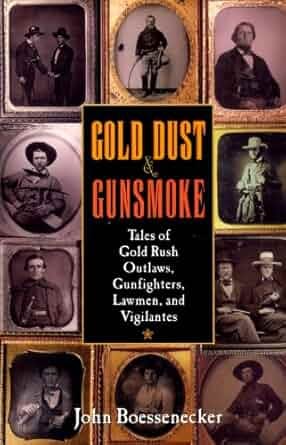

Above: The book that helped revive public knowledge of Jonathan R. Davis, by amateur historian John Boessenecker

Jonathan R. Davis never retained his fame because he never appeared to chase it in his own life. His story never became the source of Hollywood movies. It never earned the same spot in history as the OK Corral shootout. Until the publication of John Boessenecker’s Gold Dust and Gunsmoke: Tales of Gold Rush Outlaws, Gunfighters, Lawmen, and Vigilantes, the story languished in the obscurity of public archives and popular memory. It still remains a little-known anecdote from an often ignored and underwritten period of the American West.

But the middle child of Reverend Jonathan Davis didn’t ride off “into the sunset.” The records are scant, but a brief sketch of what might have become of him can be pieced together.

MARK OF CANE

Edward Cane Griffiths lived an itinerant life typical of the men who landed in Gold Rush California. Liverpudlian by birth, he left England for Ireland at age eleven and lived a life at sea. He arrived in San Francisco from Australia, alongside the men who would become the Sydney Ducks. His path seemed straight and narrow until the evening of January 19th, 1855, a full month after the Jonathan R. Davis shootout.

Griffith entered the Sonora office of Tuolumne County Treasurer Joseph Heslep at 9:00PM. He asked for a loan. Heslep refused. A bag of money was already in a bag carried by Heslep. Griffith reached for the bag. Heslep pushed Griffith back. Griffith responded by picking up an axe in the office and striking Heslep three times in his temples. A bit of an overreaction, needless to say. Griffith then proceeded to stuff paper into the victim’s mouth, stole his key, took money from a safe, and left the office.

Above: Jonathan R. Davis’ name (?) mentioned in a list of coroner jurors, Daily Alta California Volume 6, Issue 20, dated January 21st, 1855.

Investigators quickly nailed Griffith as the last man in Heslep’s office and he wrote out a full confession to the crime that night. Among the men selected as part of the coroner’s jury was a “Jonathan R. Davis.” It is unclear whether this is the same Davis since his middle name “Rutledge” was unprinted. But his participation in the jury would be consistent with the known whereabouts of Davis at this time, since it would have been two full months before his appearance in front of Judge Anderson in Placerville.

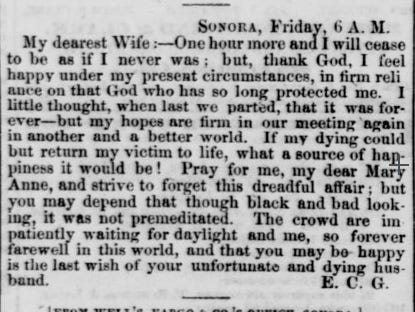

Above: Edward Cane Griffith’s final letter to his wife, published in the aforementioned issue of the Daily Alta California.

Justice proved swift for Griffith. Enraged citizens stole him from the custody of the Sheriff to be hanged the morning of the 20th. Griffith was allowed the chance to write a letter to his wife in his final hour. The letter expresses a resigned acceptance of his fate, an acknowledgement of his guilt, and a final farewell to his beloved before he was hung by the neck until dead at 7 AM.

…WHO LIVED FAITHFULLY A HIDDEN LIFE

Reverend Jonathan Davis died on October 5th, 1855 at the age of sixty-nine. He lived long enough to bury his third son Benjamin Franklin Davis, whose alcohol abuse had finally caught up with him in 1853. It’s unclear whether he was aware that his underachieving middle child known affectionately as “Jona” had become a minor celebrity on the opposite side of the country.

Jonathan R. Davis did not appear to flee California to serve in the Confederate Army as many Southerners did during the Civil War. Two of his younger brothers fought for the South. Nathan Davis was the seventh child of Reverend Davis and volunteered for the Confederate Army at the age of forty-three. West Point graduate and youngest child John Bunyan Davis captained the Monticello Guards, the E Company of the 15th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Nathan would become a newspaper editor in South Carolina. John Bunyon would practice medicine and become Sheriff of Fairfield County, South Carolina. Of the nine children of Jonathan Davis and Rebecca Kincaid, Jona would be the only one to die west of the Mississippi River. Whether he retained any contact with his family is unclear.

Unlike his brothers, the extent of Jona’s military career remained the Mexican-American War. He received a military pension in 1887 for his service with the Palmetto Regiment, and little other reward for serving as a hired gun for Manifest Destiny.

The name “Jonathan Davis” would appear with regularity in California records as the remainder of the Davis clan pursued uncertain futures. His name appears in an 1860 census as the resident of a boarding house, but lists his birthplace as Virginia and his age as fifty, when he was a forty-four year old Carolinian at the time of the census. Another Jonathan Davis appears as a cattle broker in Napa County in the early 1860s. Another shows up in Siskiyou County in 1875, this time with his middle name listed. Two years later, he’s listed as a lawyer in Douglas City.

The 1880 census is the closest record of his whereabouts. It lists him living in two different locations - Shasta County and Trinity County - but correctly states his age as sixty-four and his birthplace as South Carolina. The census lists his occupation as a miner, rather than as a lawyer. Later records throughout the 1880s find him bouncing around California’s far northern counties of Shasta, Butte, and Trinity. His age remains inconsistent on all of them - not uncommon for the time - but his occupation remains listed as a miner until he appears in Napa County in 1888. He is accurately listed as being seventy-two years old and described as a lawyer.

Assuming the records all refer to the same man, the picture they paint of Jona’s middle and senior years are typical of 19th-century California migrants seeking green pastures. When the Sierra Nevada gold fields ran dry, prospectors rushed to Siskiyou County. Men on the frontier frequently pursued avocation with equal if not greater passion than their vocation, as gambler and alleged dentist John “Doc” Holliday demonstrated. Switching his listed career between “miner” and “lawyer” suggests a restless man with a trade in his back pocket in case his prospecting pursuits failed to pay off.

Two years later, his name appears in a San Joaquin County newspaper obituary. This Jonathan Davis passed away on October 16th, 1890. His age is inflated to seventy-seven when Jonathan R. Davis would have been seventy-four, but he is listed as a lawyer who was born in South Carolina. There is no mention of the shootout in his obituary, leaving some doubt to the identity of the deceased. For all intents and purposes, it’s the closest we have to a possible death date for Jonathan Rutledge Davis.

ONE MAN WITH COURAGE

“…All that matters now is that two stood against many. That’s what’s important.”

Men frequently overrate their own grit and tolerance for terror. On Twitter, a hundred men can claim to beat a single gorilla. In the fantasies of every American man under the age of thirty-five, we know just how we’ll react in a fight and we always win. Like Neo in The Matrix, kung-fu will conveniently be downloaded into our brains at the right moment. In reality, most would break down or flee. Those who would fight when attacked usually prove less able than they expected.

Above: Another angle of Michael Trcic’s “One Man With Courage Is A Majority.”

Jonathan R. Davis said in his January 6th column in the Mountain Democrat: “I did only what hundreds of others might have done under similar circumstances, and attach no particular credit to myself for it.” But many men would not have done - or attempted to do - what he did. It’s precisely because many men lack either the fortitude or potency to fight back against an overwhelming threat that Jonathan R. Davis’ example stands out in a record of over glorified and underwhelming armed encounters throughout the old west. Most don’t know his name or story. When they learn it, they usually don’t forget it.

It’s likely not what he wanted. Given the anonymity of his remaining years, Jonathan R. Davis probably didn’t want to be remembered as a gunslinger who mowed down eleven men in a single fight. He may have wanted to be remembered as a lawyer, as a Carolinian, as a soldier, as a miner, and if the subject ever came up, he’d want to be remembered for having tried to save a friend.

Jonathan R. Davis died in obscurity according to how he apparently chose to live. Unfortunately for Jona, the inquisitive living have a bad habit of disrespecting the wishes of the distant dead.