Bring Me The Head Of Joaquin Murrieta Part VI: Yo Soy Joaquin!

The notorious winter crime spree of the mysterious Joaquin

“And

All men feared the guns of

Joaquín Murrieta.” - Rodolfo Gonzales

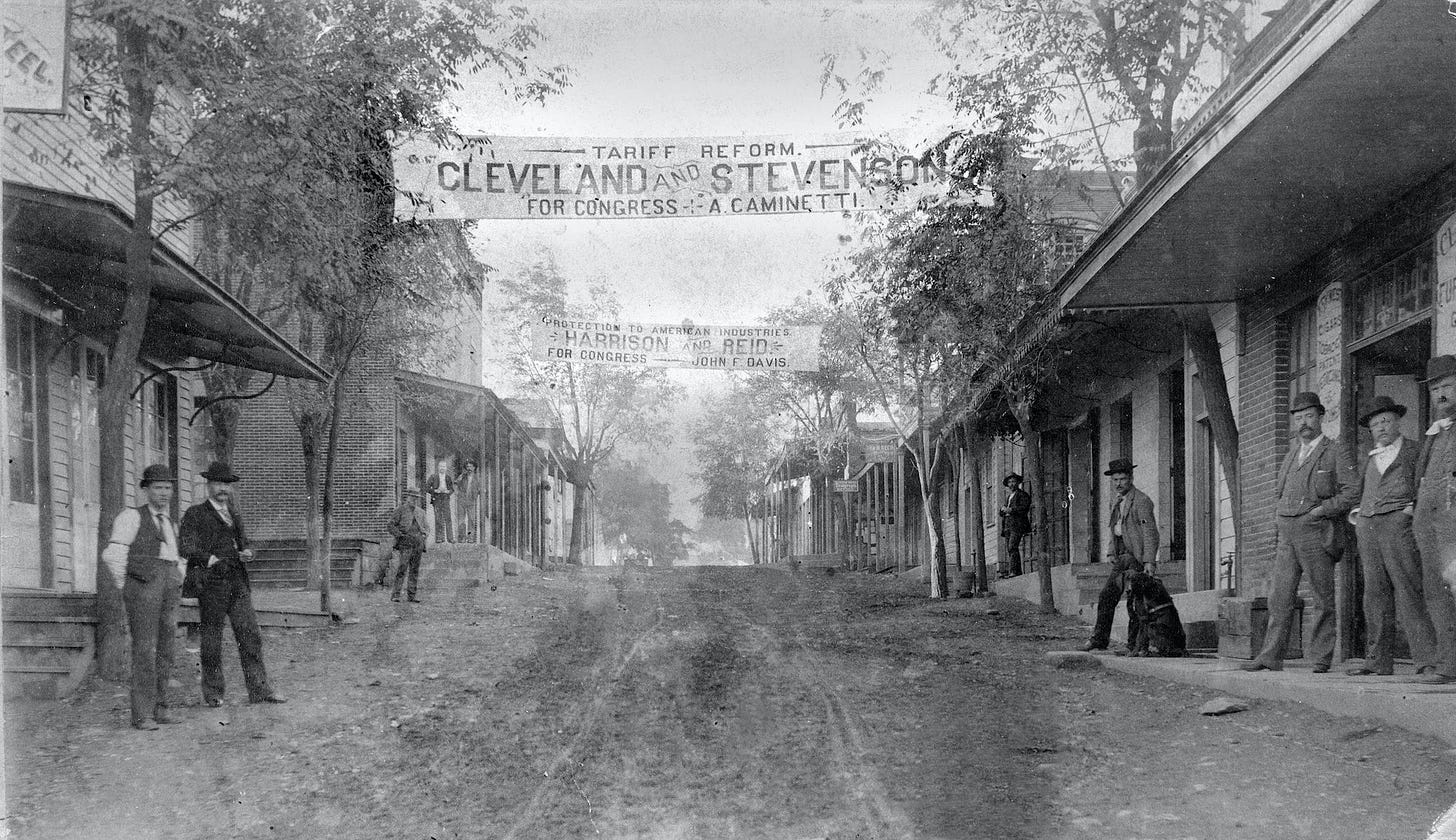

San Andreas was a small settlement founded by Mexican prospectors in what became Calaveras County, California. Its early years were spent as a tent city where even the church was made up of little more than poles and canvas. It almost died an early death as the gold reserves ran low until gold found in the river channel revitalized the town’s fortunes. San Andreas and the surrounding settlements of Calaveras County sat on the richest supply of gold in the state.

Above: San Andreas in 1892, 29 years after Joaquin’s exploits

Among the many camps nestled in the undulating hills of the county was Yaqui Camp. Named for the indigenous tribe of Sonora, Yaqui Camp was ethnically diverse and primarily Chinese in demographics. Little had improved for the situation of Chinese immigrants by the winter of 1853. The xenophobic Foreign Miners Tax earned an addendum in the form of an exclusive tax for Chinese miners that would gradually increase to an exorbitant sum of $50 a month before being declared unconstitutional. By the time the law was struck down, Chinese migrants had been largely pushed from the lucrative gold fields and forced into whatever low-paying labor jobs they could take in order to send money home to their families. But many more remained in the gold fields, determined to reap the rewards of Gam Saan. Those around Yaqui Camp were fortunate when weeks of winter flash flooding separated gold from the quartz deposits in mid-January.

By January 20th, their fortunes shifted for the worst.

The evening of January 20th, a trio of armed Mexican men entered the tent of a Chinese miner who struck rich from the gold separation. The prospectors put up a fight but the thieves made off with $160 of gold dust. Less lucky were a group robbed by a similar trio of Mexican robbers. One of the miners put up a fight and stabbed to death for his resistance. The trio took two large bags of gold dust and left behind a man who would never send gold home to his family in China.

The killing of Chinese miners attracted scant attention from the Americans who couldn’t be bothered with what Judge Roy Bean would later consider a trivial homicide. Seventy stolen horses and two murdered Americans - and a murdered Chinese man - later, the Anglos took notice. The reports of the killers’ Mexican background did little to dampen the already potent poisonous hatred felt by the Anglos towards Hispanics in the gold fields. Any wandering Mexican was suspect in their eyes. A young Mexican man was captured and escaped by slipping out of his boots to avoid alerting his captors with the jingle of his spurs. They chased him to a group of men who fired at them as the youth escaped to safe company and he and the gang disappeared off-trail.

A manhunt ensued, led by Deputy Sheriff Charles Ellis. They discovered twelve men camped uphill near the confluence of the San Antonio and South Fork Calaveras Creeks. The American posse had the advantage of coverage behind the abundant live oak and rocks along the hills and they fired their rifles at the men and struck one of them. Rather than fleeing uphill, the outlaws mounted and charged downhill towards their pursuers. Both parties exchanged enough fire to cover the air in thick smoke until the posse was empty of ammunition and the Mexicans escaped. No Americans had been shot and at least one Mexican had been wounded by the initial volley of gunfire. The otherwise nondescript hill near Pool Station Road south of the town of San Andreas is predictably known today as Joaquin Peak.

Above: Joaquin fleeing his pursuers

The band of outlaws stormed Yaqui Camp that day. They fired their guns at every Anglo they saw, retaliation for the wounding of one of their own. One of their bullets found the body of a man named John Carter and separated his soul from his body.

Evening fell. They descended upon the Phoenix Mine quartz mill near contemporary Jamestown, California. They fired at the millhouse. Two Americans inside woke in a panic and shot back at their unknown assailants. Both Americans were killed, not without mortally wounding one of the Mexicans in the mismatched fight. The outlaws left their wounded compadre to succumb to his wounds and fled into the cold January night.

The murder of the three Americans sparked the predictable outrage that the previous Chinese murders failed to rouse. Posses stationed themselves across every road and corner of Calaveras County. A Mexican man known as “Big Bill” was dragged from Yaqui Camp on suspicion of participation in the murders and was lynched unceremoniously and all other Mexicans were driven away from Yaqui Camp. The posse came across two camping Mexicans who fled in fear of the approaching Anglos. Their flight was as good as an admission of guilt as far as the Americans were concerned and they fired on the fleeing men. One died instantly. The other was wounded, captured, and strung up.

Another posse followed a trail of blood from the mill towards a river where they found the wounded outlaw dying of his wounds. The vengeful Anglos chose to expedite the slow process. A mercy killing it was not.

The situation for Mexicans in Calaveras County became dangerous. Mass meetings of miners called upon Americans to “exterminate the Mexican race from the county.” Those that refused to heed their exile notice were to be shot dead and have their property taken. Most took the warning seriously and by the 27th of January, Calaveras County had been emptied of Mexican settlers. The promise of a warning didn’t stop an enthusiastic mob from charging a Mexican man with “acting in a suspicious manner” and only the intervention of the Justice of the Peace saved him from meeting his end under a tree and surrounded by leering Americans just as Josefa Segovia and Cipriano Sandoval had.

By the end of the week, seven people were dead. Five by the outlaws, three by the posses. The Calaveras Chronicle and San Joaquin Republican reported on and closely monitored the events. In their report, they offered one vague clue to identify the leader of the Mexican gang that had stormed through the county:

“The leader of the gang is a desperate fellow named Joaquin.”

THE CHASE

The following two weeks were silent. The peace would have almost given sick credence to the possibility that the American mob’s draconian cleansing of Calaveras County had positively deterred the outlaws from their activities. But it would be the Americans who would end this silence.

On February 7th, a man was captured under the claim that he was Joaquin’s brother. They tied a noose around him and hoisted him up for a few seconds, a sample of his fate if he didn’t confess. He claimed ignorance. They hoisted him again. He desperately told the crowd he was spying for the gang to feed them the best robbery victims. They hoisted him up a third time and didn’t bring him down until after his legs stopped swinging.

If the man’s confession was true, the timing was perfect. The gang seemingly reappeared from hiding that night but instead of avenging their alleged companion, they killed two Chinese men. The hunt for Joaquin commenced. A Justice of the Peace named Thomas Beatty ordered the ferry at the Mokelumne River to be closed to crossing to entrap the bandits. His orders were promptly forgotten when the sight of revolver barrels aimed at them forced the hands of the ferrymen. Beatty and his posse crossed the river in pursuit of the marching gang.

Well ahead of their pursuers, the gang developed a pattern of robbing any Chinese men they came across. They took $1000 from a group near Dry Creek. They came upon a mining camp at Oppossum Bar and held them at gunpoint. Two men slipped away and ran towards Big Bar to warn the Anglo miners against the robbers. Bill McMullen followed the Chinese to the plundered camp. One of the campers had been shot through the neck and the camp had been stripped of $6000. McMullen gathered eleven men to chase after the gang. Still ahead of the posse, the gang robbed two more Chinese camps and stole three fresh horses to ensure a quicker pace of travel.

The gang’s violence increased as the month pressed on. Between the 11th and the 13th of February, they killed five Chinese men, stabbed an Anglo in the neck to steal his mule, and drove fifty Chinese miners from their camp for an easy theft. McMullen’s pursuit continued with a posse reduced to three others. Each time the gang came into sight of the posse, they slipped away and stole fresh horses to keep their pace quick. McMullen and his reduced posse’s fortune finally turned when they found two Mexicans nestled in the bushes in the distance. Unable to identify them from afar without alerting them, McMullen sought information and backup in the nearby settlement of Fiddletown. He left two men to keep an eye on the unknown Mexicans. One of his men approached him before he reached town with the news that horses belonging to the outlaws had been spotted not far from them. McMullen turned from town towards the horses. The remaining watchman noticed a third Mexican man leaving town with a horse. Rather than keeping his post, he left to alert McMullen of the third man and allowed the strangers to escape.

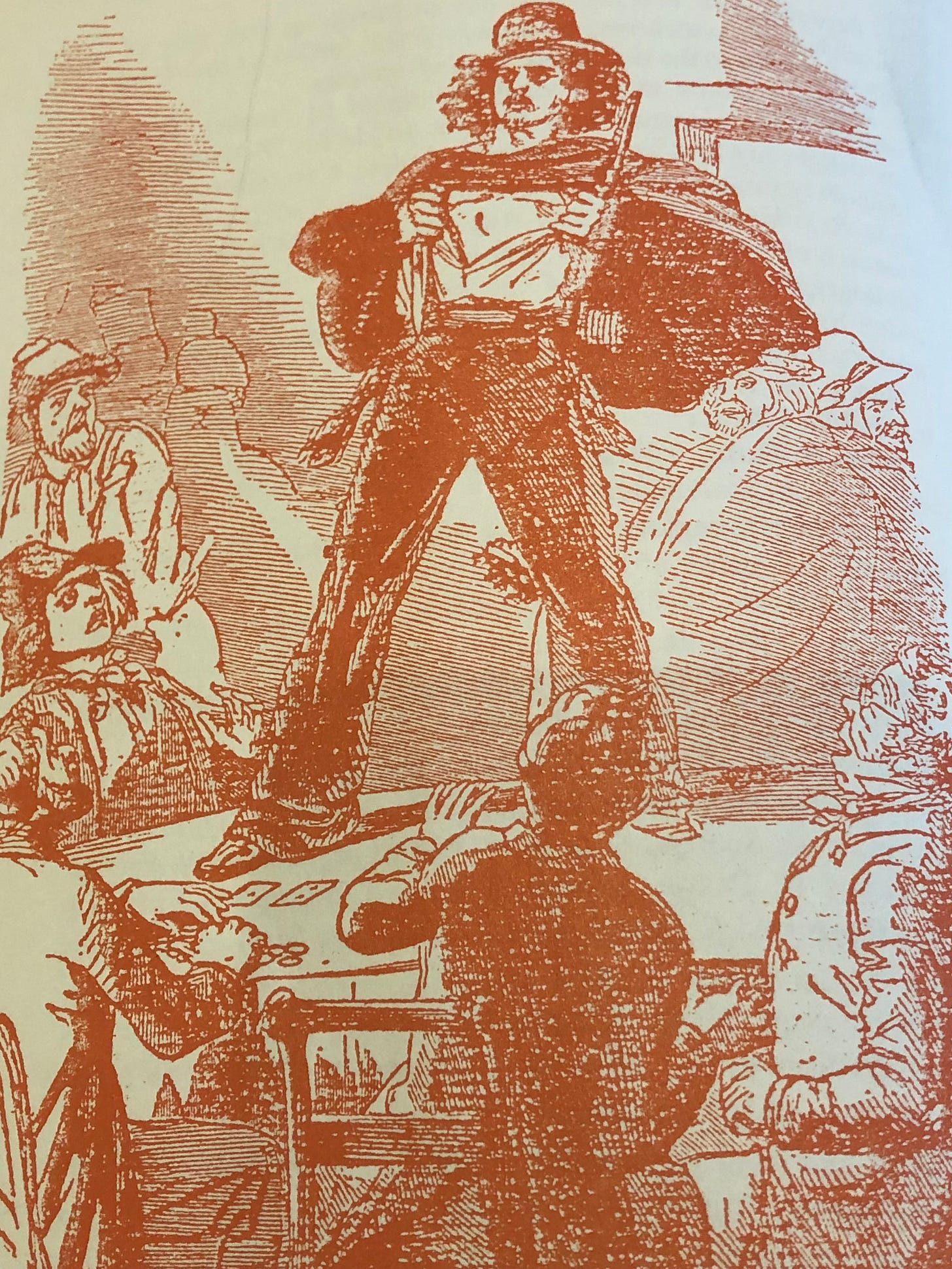

Joaquin’s presence in Fiddletown became a matter of local legend. Joaquin was allegedly spotted in gambling halls and leapt onto the table. He shouted “I am Joaquin!” and challenged anyone to take him alive. His men fled and hopped on their horses, shooting a miner in the face before fleeing. The announcement of Joaquin may be local hokum, but a Fiddletown posse did chase and exchange shots with a group of Mexicans. McMullen joined the posse while the Mexicans fled and despite being on the tail of their targets, five days of constant riding caught up to them and forced them to halt.

Above: “I am Joaquin!”

Joaquin and his gang had become the bugaboo of Calaveras County by mid-February. A false rumor that the gang had killed female stagecoach passengers whipped the population into a frenzy. A private thousand dollar bounty was posted, followed by a second thousand dollar bounty. The private reward wasn’t enough for most citizens. The blitzkrieg speed at which Joaquin and his band attacked and escaped lent them an otherworldly aura that struck fear into the hearts of Calaveras County citizens. Private posses weren’t up to snuff against this super-bandit. The mining camps alone couldn’t bring him in. A dispatch was sent to the new and temporary state capitol at Benicia in the Bay Area to Governor John Bigler to help put an end to Joaquin’s reign of terror.

HELLO GUVNAH

John Bigler became the third governor of American California on the strength of only a thousand votes. It remains the closest race in California history and he knew how lucky he was to even win. Despite the best efforts of his Southern Whig opponent to characterize the Pennsylvanian as an uncouth Yankee, Democratic Party loyalty trumped regional loyalty in the eyes of the largely Southern Democrats who made up an increasing number of California’s Anglo population.

Above: Governor John Bigler, photo taken in 1850

The good will wouldn’t last. Slavery had become a pressing issue to the large swathes of Southerners arriving in the Golden State’s southern half and finding their slaves legally freed. Referring to themselves as the Chivalry faction, they threatened to split the state in two if their demand for legalized chattel slavery wasn’t met. Bigler had managed to monopolize his position in California politics by pandering to nativist sentiments but his anti-Chinese and anti-indigenous sentiments didn’t stop him from forming the Free Soil faction of the California Democratic Party that opposed the spread of slavery into the new state. It was a moral decision and a political miscalculation. Pro-slavery Southerners were prepared to nominate their own candidate for the 1853 gubernatorial election and would rather lose the governorship than see a man of their own party promote abolition.

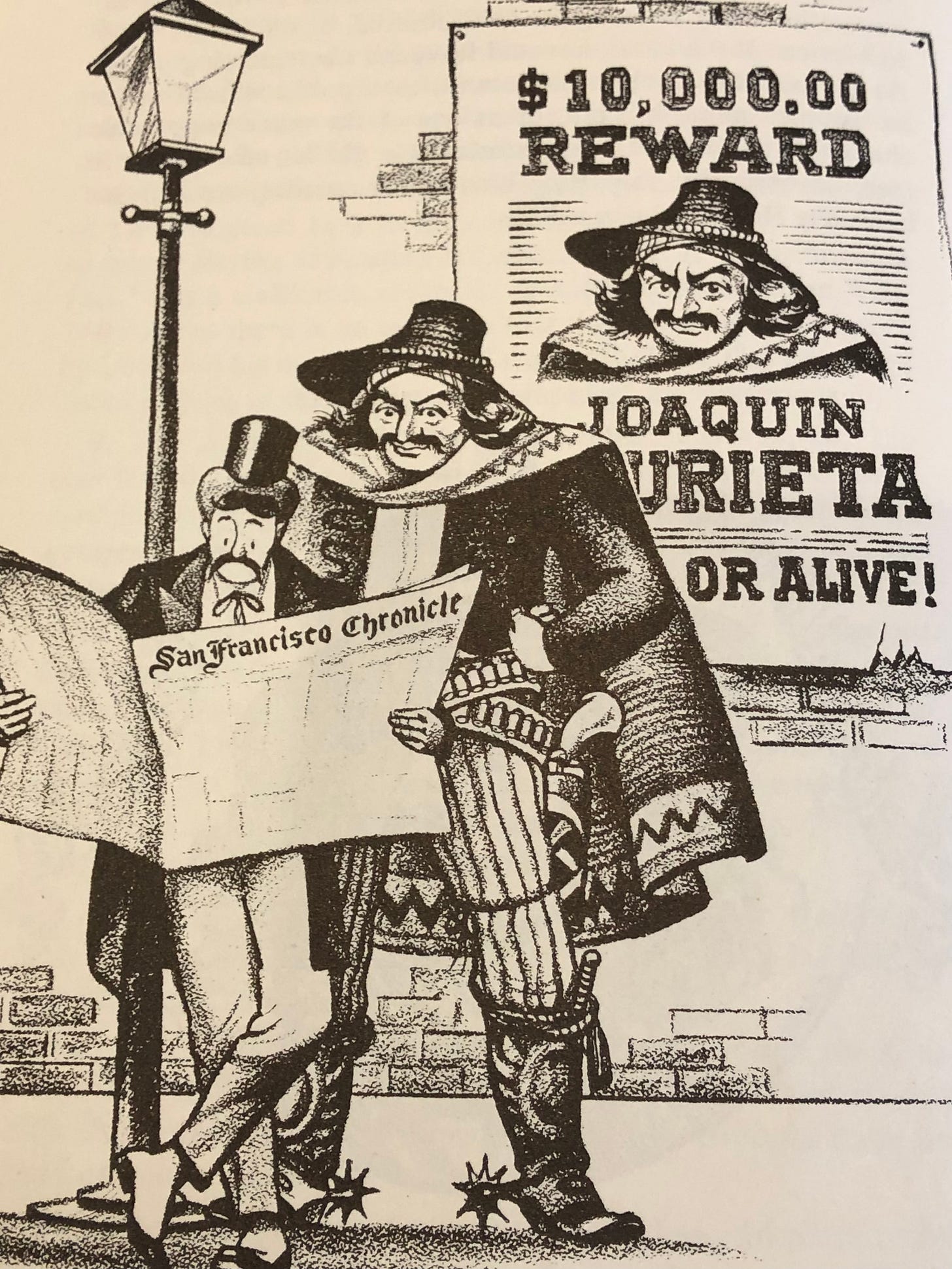

The panic around the robbery spree in Calaveras County did little to improve his chances at a re-election. Citizens demanded action. Bigler posted a reward for Joaquin on Monday, February 21st, for a reward of $1,000. The reward notice provided Joaquin the surname “Carillo” and described him as “a Mexican by birth, 5 feet 10 inches in height, black hair, black eyes, and of good address.” The inclusion of the surname was added with minimal evidence, as was the description. Those who earned their closest look at him were primarily his dead victims. The mention of “good address” squares with the later claim of Bill Byrnes that a teenaged Joaquin Murrieta received an education at a parish institution. But the name “Murrieta” would not be exclusively associated with the Joaquin who stormed through Mother Lode country until after his supposed death. Three months after the initial reward, Bigler would approve an act to muster the California Rangers against the “Five Joaquins.” Murrieta and Carillo were both surnames listed. Were they two men? Five men? One man with many pseudonyms? Were the surnames educated guesses?

The Fiddletown incident was the only situation in which the leader of a group of Mexican bandits announced himself as Joaquin. The name came from newspapers citing witnesses not thoroughly vetted or cross-referenced. While each of the facts stated in the bounty could have been true, no witness claimed enough intimacy with Joaquin for each of the attributes to completely apply to the leader of the gang. Even the possibility that each crime had been committed by the same gang was suspect to some. The Los Angeles-based El Clamor Publico published a piece in June 1853 titled “Quien Es Joaquin?” in which they raised the possibility that a series of random robberies and killings had been lazily attributed to the same man. The charge resembled the tendency for any robbery around Missouri in the 1870s to be associated with Jesse James, regardless of his actual involvement. Always better to have been robbed by a celebrity bandit than a random nobody.

If the robberies and killings had all been the same gang, then it was the work of men whose chief brilliant strategy was to know where to find fresh horses and who wisely abandoned exhausted mounts at every possible point in their flight through the mountains. The speed at which Joaquin appeared and disappeared only fueled the paranoid rumors that he commanded an army of bandits as far south as Mexico City ready to upend the Anglo order at a moment’s notice. But Joaquin never attacked any power centers of American occupation. He never led his men against American politicians or American landowners or American law officers. When Hispanic men supposedly in his employ were lynched, his act of vengeance never focused on the lynch mobs and was always random.

Such was the case when a man named Antonio Valencia was captured and accused of working for Joaquin by a Mexican woman on the 15th of February. Valencia confessed to participation in the robberies but insisted he never murdered anyone. The lynch mob hoisted him up while a Catholic priest failed to procure a confession necessary for last rights. One imagines strangulation provides a barrier against confession. Joaquin and his men robbed a German man of $600 on the road the following day but the lynch mob remained unpunished. Rather than fleeing immediately, the gang loitered around Sutter Creek in a chaparral field and were surrounded by an American posse alerted by the mugged German. One of his men was killed by the gunfire volley. Joaquin himself was struck in the cheek. The men fled and disappeared into the chapparal thickets, shaking their pursuers again. Even after a posse of 50 Americans and 100 Indians were mustered, the gang managed to slip away.

On February 20th, Deputy Sheriff Charles Ellis received information that a member of the gang was shacked up in Los Muertos near San Andreas. It had been the very man struck by a bullet at Joaquin peak, resting to recuperate from his wounds. Ellis arrested him and drug him into San Andreas where he received a lynch mob trial and was unceremoniously hung. As with the previous incidents, the gang struck back immediately. Their target this time was a Chinese mining camp that they robbed of $10,000 and left behind with three dead Chinese men and five wounded. Sloppy luck saw them attempting to steal horses from the same stable that Charles Ellis and his posse were camped in. One of the gang was shot in the hand but they were otherwise unharmed as they fled over a mountain and came upon yet another Chinese camp. They robbed it of $3000 and three men’s lives. The posse pursued them down the mountain, a mere ten minutes behind them. At dawn, a third Chinese camp had been robbed, each robbery occurring within a mere sixteen hours.

Bigler’s reward had been posted prior to this spree. Following it, an additional thousand dollars seemed an inefficient method of spurring the state’s law officers into action against the gang. Calaveras County was in a panic, as were the neighboring counties. Americans considered more distant locations for gold mining like Australia. Chinese miners fled for the safety of settlements occupied by the same whites who tried pushing them out. The Calaveras Chronicle reported that “Joaquin and his party are not to be taken by any ordinary means.” The consistent failure of multiple posses seemed to prove the paper correct.

ESCAPE

Frightened prospectors weren’t the only ones fleeing the gold fields. Calaveras County proved too hot for Joaquin and his men. They fled south, out of the heart of Mother Lode country until they reached the foothills of Mariposa County. Mariposa bordered the San Joaquin Valley and sandwiched Tuolumne County between itself and Calaveras. It was the perfect place to rest away from the angered posses. Their new haunt was Hornitos. Hornitos was a Mexican settlement founded as a refuge for Mexican miners forced from their claims by gringo greed. Demography and the reputation of Hornitos as a gambling town meant that Joaquin fit right in. He may have been too comfortable in town. According the the San Joaquin Republican, Joaquin had imbibed in so much liquor while playing montebank that he might have slipped his identity at the table if not “for the timely entering of three of his band who carried him off by force.” He didn’t stay gone for long. Two Americans recognized him and attempted arrest. He wounded them with the aid of Samuel Colt’s invention and escaped without a scratch.

Above: Artist’s representation of Joaquin Murrieta

The day after the shooting on March 4th, a posse followed the tracks of rustlers who stole livestock from a Quartzburg ranch and found a tent in Hornitos. A posse of eight Americans surrounded the tent. The rancher, named Prescott, entered and the entire posse found themselves under fire from outside the tent almost instantly. Those inside the tent made their break. Americans shot blindly at anything that moved and hit nothing. Prescott and a man named Henry Crowell were both shot and injured while the gang made another daring escape. Six days later, Joaquin attended a dance hall and was spotted. He and his men fired at their attackers and killed two or three before escaping yet again. A night later, five Frenchmen were attacked on Bear Creek, robbed and killed. No evidence pointed to any solid culprit, but newspapers were almost certain that the killers were Joaquin’s gang.

Barring the murdered Frenchmen, the dance hall shootout became the last verifiable incident involving Joaquin and his gang in the Sierra Nevada region. Joaquin and his gang had escaped, but they also vanished. For the first time since storming the news cycle in January, they fled into obscurity where they couldn’t be followed. But the Anglos didn’t forget the crimes committed by the gang. Joaquin became the object of terror for months after he had ceased to be a credible threat.

FOUR REVOLVERS AND A BOWIE KNIFE

Joaquin’s crime spree as a bandit leader was brief and bloody. His wanton murder of Chinese miners bears none of the hallmarks of an avenging Robin Hood so commonly associated with the legend of Joaquin Murrieta. Why the Chinese were singled out specifically can never be fully answered, but the hard truth is that they were unarmed and largely outside Anglo protection, thus easy targets. But the relative brutality inflicted on the Chinese miners and the consistency of the attacks compared to those against Anglos suggests a racial animus common among prospectors and settlers grown envious and paranoid over the presence of Chinese miners as the wealth of the gold fields dwindled.

Joaquin appeared in the papers again the following April. A group of vaqueros visited the rancho of Francisco Pacheco in the Salinas Valley. Pacheco, an elderly landowner who watched California change hands twice in his life, described the leader of the vaqueros as a “tall, handsome man about 21 years old with a long beard” who carried “four revolvers and a Bowie knife.” The men asked for food. Pacheco obliged. Pacheco inquired the leader if he was the very Joaquin who had become notorious in the mining camps. Joaquin didn’t dodge the question. He confessed that he had been driven out of every business endeavor he tried his hands at by the greed of the Americans. He justified his crimes by saying he followed the example taught to him by cheating and stealing others. He never explained why the wrongdoings of the Americans made him so hard on the Chinese. He also claimed that when he came across a reward notice for $5,000 posted by a Chinese businessman that he wrote underneath “I will offer $10,000 myself - Joaquin.”

Pacheco’s story was published in the San Joaquin Republican. Left unmentioned was his relation to Claudio or Reyes Feliz, though the San Joaquin Republican claimed with minimal evidence that the so-called “Joaquin Carillo” was actually named Joaquin Murrieta. Outside of Pacheco’s story, Joaquin’s whereabouts remained the subject of feverish rumor and creative hearsay for the next three months as paranoid Anglos transformed a highway robber into a potential revolutionary set to overthrow the new American order in California. He had become a celebrity bandit too big for the state government to ignore in an election year. A bandit who made as much noise as Joaquin required more than local posses. It required a proper militia. It required men accustomed to hard rides across the precipitous California countryside.

It required what would become the California Rangers.

Coming next: Two men with ties to Joaquin join the California Rangers in the desperate hunt for the desperado in Bring Me The Head of Joaquin Murrieta Part VII: A Man Called Love