In 1980, 125,000 Cubans arrived in the United States over a series of six months in a program known as the Mariel boatlift. The full background behind the boatlift is far too long to discuss in full detail, but the basics are as follows:

Following a relaxation of both the US embargo of Cuba, a relaxation of Cuban emigration policies, and a diplomatic crisis in which large crowds of Cubans entered the Peruvian embassy seeking asylum, Fidel Castro announced the opening of the Mariel port to anyone seeking to leave Cuba for the United States. What began as a small trickle spiraled into a flood as large numbers of Cubans dissatisfied with the Castro government rushed to the coast. A state of emergency was declared. The US Coast Guard unsuccessfully attempted a blockade of all boats coming in until the program ended in October 1980.

After the first boats landed, the fearful rhetoric began. Initially welcomed as a new crop of patriotic anti-socialist Americans fleeing communism, the boatlift was treated by the press and politicians as a Trojan Horse tactic for Castro to dump Cuba’s criminals and social undesirables onto US soil. A speech by Castro deriding the marielitos as unwanted members of the lumpenproletariat didn’t help the matter. By 1981, Florida Governor Bob Graham testified before congress blaming the refugees for the rising crime rate in Miami. In 1985, it was reported that 25,000 of the 125,000 marielitos were criminals.

The truth was far more nuanced. Most of those with criminal backgrounds were jailed for minor crimes, some of which were not considered criminal to the United States (such as selling US goods on the black market). A large number of homosexuals were granted special privilege to leave the country. Of the 125,000 marielitos, only about 2,700 had been jailed for serious crimes in Cuba.

But the data didn’t matter to many Americans who heard the rumors that Castro was creating a Cuban crime invasion in Miami. By 1980, Miami was already a hotspot for drug trade activity due to its convenient location for drug smuggling across the Caribbean. The already existing crime wave was blamed on those new arrivals who landed in a modern-day Caribbean pirate haven. Not helping the matter was the difference in the racial makeup of the marielitos compared to the pre-existing Floridian Cuban community. The first wave of post-revolution Cuban exiles were largely white Cubans from bourgeois backgrounds. The marielitos were largely working-class Afro-Cubans who were socially shunned by the old arrivals, leaving many without work or the social safety net of the community. Which is to say, leaving them in the perfect position to turn to crime out of desperation.

To this day, the Mariel boatlift is most remembered as the backdrop for the Brian DePalma movie Scarface. The small number of actual hardened criminals among them smeared the image of the 125,000 marielitos hoping for a warm welcome from the US. And Miami, already the Barbary Coast of the new decade, became the face of a new wave of organized crime driven by the American demand for cocaine.

The same happened in 1850s San Francisco when the Australians arriving on California’s coast in the hopes of riches and a new life became associated with the small numbers of hardened criminals among their ranks who took control of vice in the developing city. For two years, Sydney Town became synonymous with the worst that San Francisco had to offer.

IF YOU’RE GOING TO SAN FRANCISCO…

The 550 square-mile San Francisco Bay is the largest estuary on the west coast of the United States, which destined it to be the primary sea port of the 19th century American West. The process by which it became the “Paris of the West” was far from gradual.

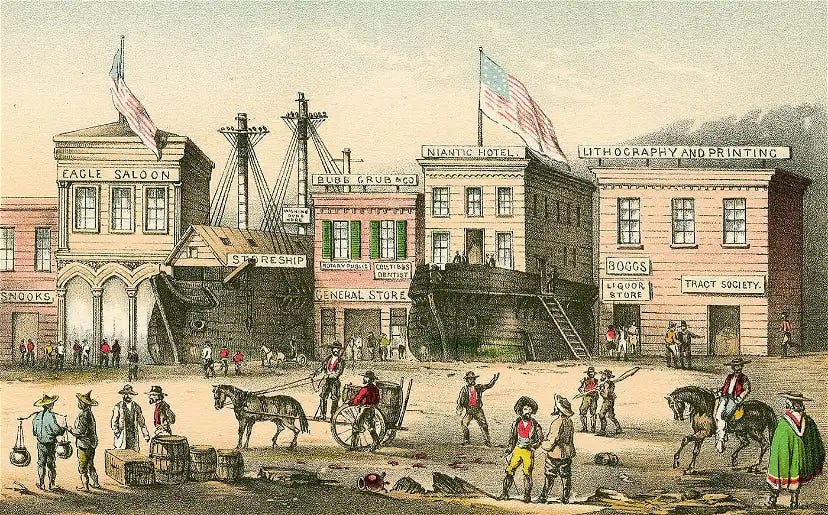

Above: San Francisco in 1949

The flood of migrants that followed the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill caused the population of San Francisco to boom from a mere one thousand in 1848 to around 25,000 people by the end of 1849. The chaotic growth spurt of San Francisco saw men from different corners of country and from across the globe clustered together along the peninsula, many of them having no desire to co-exist with either foreigners or fellow countrymen who could be considered competition to quick riches in the gold fields.

San Francisco soon developed a reputation for vice and violence. The gender disparity created a market for prostitution. Saloons and gambling halls sprang up along the long stretch of Pacific Avenue east of Stockton Street below Telegraph Hill. Ever-flowing booze fueled the fires that burned inside the angry young men who flocked to the Golden State and soon the fires spilled into the streets of San Francisco.

Among those angry young men were a group of discharged fighters from the 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers. Some among the New Yorkers were former members of the Bowery Boys gang, a loose group of anti-Catholic nativists immortalized in the Martin Scorsese film Gangs of New York. The Bowery Boys were the muscle of the xenophobic Know Nothing Party, serving as a plainclothes Brownshirt division devoted to brawling Irish Catholics in the neighboring Five Points ghetto. Their strong opposition to anything neither Anglo nor Protestant made them ideal volunteers against Mexico. For them, the war didn’t end with their discharge. Like many filibusters along the borderlands, the former Bowery Boys in San Francisco continued to wage the war of Manifest Destiny in the streets.

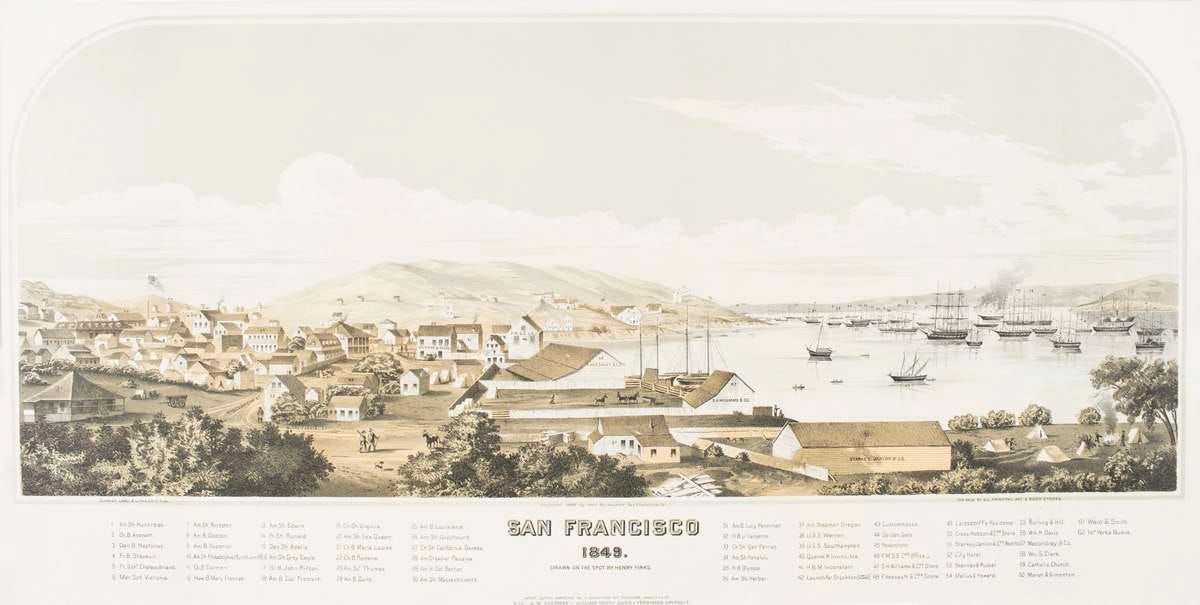

Officially named the San Francisco Society of Regulators, they were more infamously known as the Hounds. Swarming the streets at night, the Hounds targeted Mexicans and Chilean immigrant neighborhoods and encampments. They beat them, robbed them, and tore down their dwellings. Those who didn’t wish to meet that fate paid a hefty protection sum, not always with the guarantee that the Hounds wouldn’t attack them anyway.

Few Anglo residents paid much mind to the activities of the Hounds. Battered Hispanics were low priority victims, even when the Hounds began extorting Anglos. But on July 15th of 1849, Hounds overplayed their hands when they attacked a Chilean encampment in the city and opened fire on multiple unarmed emigres.

Above: Artistic interpretation of the Hounds’ attack on the Chilean encampment

Even those previously apathetic to the Hounds’ activities were outraged by the bloodshed. A group of citizens, including newspaperman and founder of the Daily Alta California Samuel Brannan, lobbied the alcalde to organize a temporary police force - San Francisco lacked any proper standing law enforcement agency at this point - to put down the Hounds. Two-hundred and thirty men were organized and deputized within a day of the Hounds’ massacre of the Chileans.

The Hounds read the writing on the wall. Most fled San Francisco, though not before their most prominent members were arrested. Gang leader Samuel Roberts and nineteen other men were swiftly tried, convicted, and sentenced to ten years of hard labor. None of them served their full sentence. Influential members and sympathizers of the Know Nothings successfully helped overturn the sentences of the convicted men. But the overwhelming show of force against the gang prevented them from reorganizing, their membership scattered across the state.

A month after the Hounds affair, the San Francisco Police Department was officially organized on August 13, 1849. Appointed to oversee the nascent department was a thirty-five year old Irish barkeep from New York named Malachi Fallon. Fallon’s time working at New York City’s Tombs Prison made him an ideal candidate and he mustered a force of thirty officers, three sergeants and a Deputy City Marshal to enforce order in a city with a population reaching almost thirty-thousand.

By all accounts, the first officers of the SFPD were little more than crooks themselves. Writing in a journal about his time spent in San Francisco, Frenchman Albert Bernard de Russailh remarked,

“The police force is largely made up of ex-bandits, and naturally the members are interested above all in saving their old friends from punishment. Policemen here are quite as much to be feared as the robbers; if they know you have money, they will be the first to knock you on the head. You pay them well to watch over your house, and they set it on fire. In short, I think that all the people concerned with justice or the police are in league with the criminals.”

Needless to say, the new police department did little to quell the chaotic crime wave. They were neither particularly respectable nor dependable. California in 1849 was still only a US territory, in the midst of a messy transition from Mexican to US legal codes, with an unreliable judicial system that compelled those less patient with the long process of a criminal trial to turn towards vigilantism. San Franciscans sick of crime and municipal corruption never forgot the example of their neighbors who organized by the hundreds to remove the Hounds from their streets.

It was a lesson they would keep in mind when the Sydney Ducks set the city aflame.

FORGET IT JAKE, IT’S SYDNEY TOWN

The long stretch of Pacific Avenue south of Telegraph Hill - known as Pacific Street at the time - has popularly been known as the Barbary Coast. The name was bestowed upon the red-light district by sailors who borrowed the name from a popular term for the North African coast notorious among European sailors as a haven for Muslim pirates, such as those the US Navy fought during the First Barbary War (the “shores of Tripoli” line in the “Marine’s Hymn” refers to this incident). The comparison to a pirate’s haunt was apt. The San Franciscan Barbary Coast was like a mainland Port Royal, a nest of vice where sailors, miners, and transient souls could indulge themselves with minimal impunity.

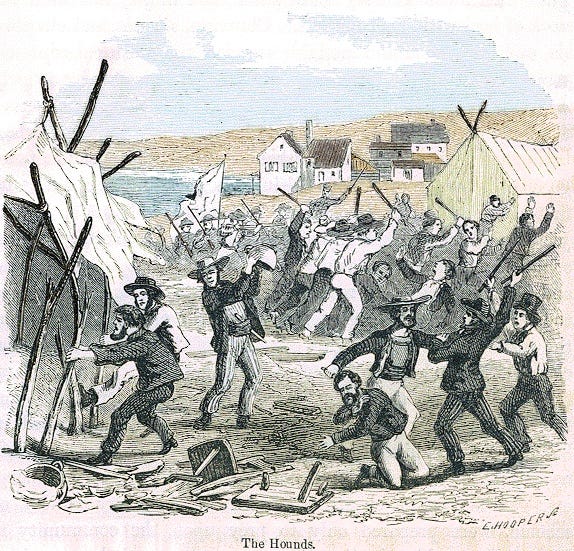

Above: Photograph of Portsmouth Square pointed towards Telegraph Hill, 1851

But the Barbary Coast designation was a later development. During the early years of the Gold Rush, the Pacific Street district was known for a different coastline. One that the majority of its residents had sailed from in the hopes of a new life. In the early 1850s, it was called Sydney Town.

Sydney Town wasn’t strictly a red-light district. Teamsters, barkeeps, wash women, longshoremen, all varieties of working-class professions made up the majority of the poor neighborhood’s Australian population. But the roster of saloons and brothels expanded with the Australians opening their own establishments and coming to dominate much of the vice in the neighborhood. Australia’s reputation as a penal colony was already well known to Americans, and the influx of ex-cons into San Francisco did nothing to improve the reputations of regular Australians who tried distancing themselves from their disreputable brethren.

Entering the vice business was a sensible decision for many of the Australian ex-cons since it provided faster cash than either prospecting or labor, and more than a few Australians in San Francisco had experience in barkeeping. The saloons were built out of whatever materials were available, but many were built out of abandoned ships. The Old Ship Alehouse was nothing more than a hulk in the waterfront, its entrance consisting of a gangplank that led into a crudely cut hole in the side of the hull. Old Ship Alehouse owner Joseph Anthony was an Australian ex-con who advertised his establishment with a sign promising “Gud, bad and indif’rent spirits sold here! At 25 cents each.” Aussie humor at its finest.

Above: A model of the Old Ship Alehouse as it would have looked in the Gold Rush days

The Sydney Town saloons had the colorful names typical of waterfront dives and countryside pubs such as the “Jolly Waterman” or “the Magpie.” They were all dives that developed dangerous reputations for being flytraps where unsuspecting drunks would be robbed and assaulted by the local gang members who extorted residents and visitors alike. Rumors spread that many of these saloons contained trapdoors to capture men and sell them into forced labor at sea. The trapdoor story is likely hokum - there are far easier ways to entrap someone than a Looney Tunes gag - but the Sydney Town saloons were indisputably dangerous places to wet one’s whistle.

A few of the saloons offered unique attractions beyond food, drink, and prostitutes. The Fierce Grizzly featured a grizzly bear chained outside to presumably greet guests with a big bear hug. The Goat and Compass was the haunt of a local named “Dirty Tom” McAlear, a man who ate anything offered and claimed to have not bathed for a decade and a half. Some of the saloons were exceptionally perverse. The Boar’s Head boasted a live show involving a woman and a wild boar. I’ll leave the lurid details of such a show to the imaginations of the readers.

The loose association of criminals who operated in the saloons and made money off vice, theft, and extortion became known as the Sydney Ducks. The exact origin of this moniker is unclear. Records show the Sydney Ducks also being referred to as the Sydney Coves. Possibly a reference to their migratory status, possibly a reference to the waddling gait many ex-cons developed from years spent their legs shackled, the Sydney Ducks became the catch-all name for the Australian-based criminals who ran the neighborhood. Ironically, few of them were from Sydney. Most of the ex-cons came from Van Diemen’s Land, now known as Tasmania. Presumably few Americans had heard of Tasmania and fewer still had the foresight to name the gang the Tasmanian Devils.

The Sydney Ducks and Sydney Town became synonymous with everything wrong with San Francisco. But the reach of the Ducks extended beyond their enclave and began to infect the rest of the city. Eventually, like the Hounds before them, the Sydney Ducks would overplay their hands while expanding their operations to a new specialty.

Arson.

WE BURNED THIS CITY

Dennison’s Exchange was the polar opposite of the Boar’s Head in atmosphere. It was an upscale joint on Portsmouth Square, a popular spot for gamblers who preferred losing their money to losing an eye or their teeth.

Above: Artistic rendering of Portsmouth Square during the Gold Rush. Note the businesses made from ships.

It was also in operation for less than a year.

Christmas Eve, 1849. A fire breaks out at Dennison’s Exchange that soon spreads across Portsmouth Square. By the time the fire is extinguished, much of the district is destroyed in the figure of millions of dollars worth of damage.

Curiously, the fire never spread to Sydney Town. The winds blew southwest, away from the red-light district. Rumors spread that Dennison’s Exchange had denied demands for protection money from the Sydney Ducks, that the fire was a punishment and a message to any who would refuse to pay up in the future. Whatever the case, Sydney Town remained unscorched. It wouldn’t be the last time that a fire would conveniently spread away from Sydney Town.

May 4th, 1850. Another fire breaks out at Portsmouth Square. The pattern repeats a month later when four-hundred buildings burn down, devastating the heart of the bustling city and conveniently destroying competing gambling houses that would rob Sydney Town of business. Once again, Sydney Town is spared since the winds blew the flames the opposite direction.

The fires provided the Sydney Ducks convenient cover in the form of chaos. With panicked eyes directed towards Portsmouth Square, the Ducks would swarm the streets and burglarize unattended businesses. Occasionally they posed as Good Samaritans offering to rescue belongings in burning buildings, which they proceeded to do without returning them to their owners.

Virtually everyone in San Francisco suspected the Sydney Ducks of arson. But there was neither evidence to tie the fires to the Australians nor an adequate police force capable of investigating and arresting them. San Francisco’s city council passed a curfew requiring all Sydney Town establishments to close by midnight. It was an unenforceable ordinance that accomplished nothing more than the legal equivalent of a designated bed time. Before the year was out, a fourth fire struck San Francisco on December 14th.

May 3rd, 1851. An hour before midnight, a fire breaks out in a paint store located above a Portsmouth Square hotel. Fierce winds spread the fire across the square and downtown at an alarming speed. The wood plank sidewalks of the downtown district fuel the fires as the volunteer fire department struggles to suppress the flames. Citizens run into “fireproof” brick and iron buildings and suffocate inside because the heat causes the iron doors to expand, sealing the doors and preventing escape.

Above: A painting of the great fire of 1851

The fire raged until around 9:00 AM the following day. The flames could be seen from across the Bay, giving San Francisco a hellish appearance from a distance. When the last of the flames had been extinguished, eighteen blocks had burned to the ground. The Niantic Hotel, built out of a former whaling ship, and a general store owned by Italian immigrant and future chocolate baron Domenico Ghiradelli were among the 2,000 structures destroyed. At least nine people perished. Three-fourths of San Francisco lay in ruins, with only the outskirts and the waterfronts untouched. Including Sydney Town.

An investigation into the fire pointed to two Australians from Sydney Town named Jack Edwards and Ben Lewis. The pair were arrested and charged with arson. Their time behind bars didn’t last before the judge released them, allegedly the result of bribery. Once again, the system failed to deal a blow to the Sydney Ducks.

LET ‘EM SWING ‘TIL THE SUN GOES DOWN

The horror of the fire still loomed in the minds of San Francisco residents when a small fire occurred in the early Saturday hours of June 7th, 1851. The fire was extinguished quickly, with evidence of deliberate arson left behind. A wharf watchman reported a man fleeing the area before the fire broke out.

The incident was reported on the June 9th edition of the Daily Alta California. The column lamented the constant crime in San Francisco and exhorted San Franciscans to “arouse themselves, and take some measures for the protection of themselves and their property.” The column added:

“Let a public meeting be called immediately, and let some simple but determined plan of action be agreed upon, by which we may rid ourselves of the incendiaries and burglars who infest our city. Many of them are known to the police, and they should be searched out, and fair warning given to them to leave the city immediately or take the consequences of disobedience to such an order.”

The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance was formed that same day with seven-hundred names in their roster.

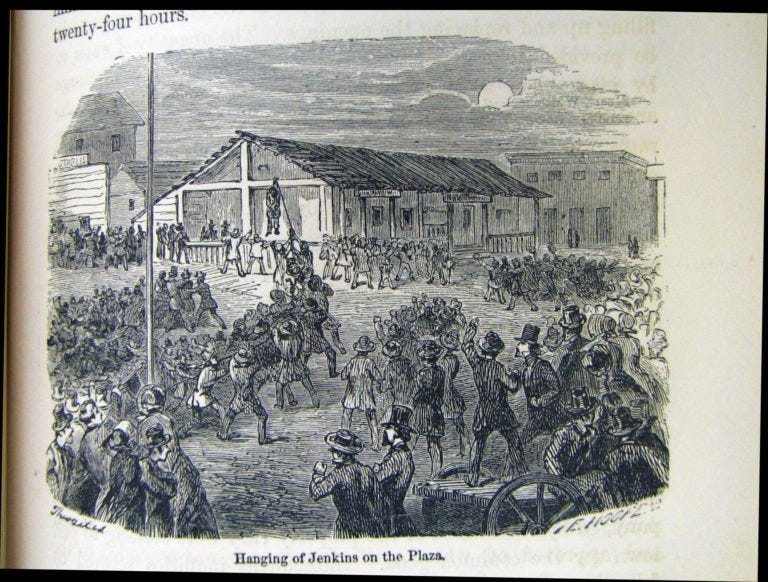

The Vigilance Committee was swift to act and administer their notion of justice. The following day on June 10th, they caught an Australian named John Jenkins attempting to break a safe he had stolen from an office. Nicknamed “The Miscreant,” Jenkins was a seasoned ex-con with a reputation for violent robbery. Possession of a stolen safe was all the evidence needed to secure the unanimous conviction needed by the Committee to pass down the sentence of death. The Vigilance Committee hung Jim Jenkins in the Portsmouth Square plaza, and they watched his legs kick in the air while the noose slowly strangled Jenkins.

Above: Drawing of John Jenkins’ hanging

Jenkins’ hanging sent a message to the Sydney Town criminals and soon many Australians piled into ships to flee San Francisco. It’s unlikely all those who fled were criminals. The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance reinstated an old law of Mexican California that prevented foreign criminals from immigrating, a law that had still been on the books and was completely unenforced - and indeed, unenforceable - during the population boom of the Gold Rush. Such a law was broadly applied by the Committee to include those harboring foreign criminals, which given Australia’s history as a penal colony, could have included virtually any Australian cohabiting with ex-con friends, relatives, or spouses. Any Australian was at risk of deportation for the simple crime of being Australian. Fearing the ambiguity of the law and the loose way vigilantes tend to apply the law, many Australians simply left before they could potentially suffer the indignation of being sent to Australia in irons. Again.

Not all left without sending their own message. On June 22nd, a sixth fire burned Portsmouth Square in the middle of reconstruction efforts. It would be the last of the great fires for many years.

ENGLISH JIM

James Stuart started his career early when he was convicted of forgery at the age of sixteen. He was sent to Australia in the 1830s, where he remained until 1847 when he was granted a ticket-of-leave and he sailed for New York. His prison stint in New South Wales did little to rehabilitate him when he landed in New York City. He spent much of the rest of the decade robbing and swindling his way along the east coast until he heard the call of gold and arrived in San Francisco in early 1850.

By most accounts, Stuart - known to some as “English Jim” - didn’t stick around Sydney Town as frequently his criminal compatriots from Down Under. Inflation had skyrocketed in San Francisco to an obscene degree. A month’s stay in a hotel could rack up to $1,000, $30,000 in today’s money. One restaurant charged a dollar for a single slice of bread, two dollars if the bread was buttered. There was little incentive for someone without a steady income stream to stay in the city, and even less incentive for a man who learned alternative means of making money to stick to labor or prospecting. English Jim returned to crime, graduating beyond forgery and swindling to armed robbery and murder.

December 1850. Sheriff Charles Moore of Yuba County is found murdered in his own home, with $4,000 missing from the house. Evidence pointed to English Jim as the perp, so he was arrested and detained in Marysville. His jail stay was remarkably shorter than his time in Australia. Within a few days, he had already escaped and fled for San Francisco.

February 1851, 8pm. C.J. Jansen & Co. co-owner and proprietor Charles Jansen is savagely beaten and robbed of $2,000 by two men in his own San Francisco dry goods store. One of the men is English Jim (given his killing of the Sheriff, one wonders if Jim simply had a problem with men named “Charles”) and Jansen offers a description of his attacker that corresponds with Jim Stuart’s appearance.

But the police arrest a different Aussie named Thomas Berdue. Berdue bore an uncanny resemblance to English Jim, so much so that Jansen himself identified Berdue as the attacker. Word spread that English Jim had been captured and the police had to hold back a mob that wanted to lynch the murderer of the Yuba County sheriff. Photographs were a rarity in 1851 California. There were few practical means of correctly identifying a criminal only a handful of people had laid eyes on, a problem that would occur with Joaquin Murrieta two years later. Needless to say, no one listened to Berdue’s protestations that the police had identified the wrong man.

Berdue attempted to argue his innocence during an arraignment that was interrupted by a mob determined to see immediate justice carried out. The arraignment was postponed for the following day, with a jury unable to decide on a conviction for Berdue or for the man who had been identified as his accomplice, Robert Windred. On March 14th, both Berdue and Windred were found guilty and sentenced to fourteen years incarceration. Windred escaped before his sentence could be carried out, but Berdue’s troubles hadn’t ended. He still Sheriff Moore’s murder hanging over his head.

Berdue was transferred from San Francisco to Marysville for the murder trial, which began on June 28th. Evidence had already determined that Jim Stuart was responsible for Moore’s murder. The open question was whether or not they were actually trying the real Stuart or not. Berdue continued pleading his innocence. Enough witnesses determined that Berdue looked enough like Stuart that it could well have been him. Unable to make his case, Berdue was found guilty on July 4th 1851 and sentenced to hang.

Fortunately for Berdue, the real English Jim made the fatal error of attempting to rob a ship docked in the San Francisco waterfront on July 11th. The crew caught him, subdued him, and handed him to the Vigilance Committee to be tried.

Faced with the certain fate of a lynching, Stuart didn’t even bother concealing his identity or his crimes. He confessed to being the real English Jim, confessed to the robbery-homicide of Sheriff Charles Moore, and confessed to robbing Charles Jansen. He also provided the names of two former associates to the Committee, fellow Sydney Ducks Samuel Whittaker and Robert McKenzie.

Stuart’s snitching on Whittaker may have contained an ulterior motive. Both Stuart and Whittaker were paramours of an innkeeper named Mary Anne Hogan. Like Stuart, Hogan was born in England and - depending on who you asked - either migrated to Australia as a toddler with her family or was sent there as a teenager for robbery. She met her husband in Australia and immigrated to San Francisco, where they opened a pub on Sansome Street that reputedly doubled as a safe house.

According to her own testimony, Mr. Hogan left for business in Oregon. Poor realty decisions drained his funds, and Mary Anne began her dalliance with Samuel Whittaker. Whittaker boarded at Hogan’s house for a fee of $20 a week. Hogan was under no illusion of the sort of man Whittaker was. Many of his criminal compatriots frequented the Hogan house, including English Jim Stuart. One night, a man armed with a dagger entered the house with the intention of killing Whittaker. The fate of the knife-wielder remained unknown to Hogan, although she suspected a corpse that turned up in Sydney Town not long after may have been the fate of the cuchillero.

Mary Hogan attempted to steer Whittaker away from criminality, sending him away to the gold fields twice in the hopes of reforming him. He returned with money, unlikely to have been earned from mining. Two police officers who learned of Whittaker’s winnings arrived at Hogan’s doorstep and warned her that they would arrest Whittaker if he didn’t offer them a taste. San Francisco’s finest at work.

The wrongful arrest of Thomas Berdue affected Whittaker greatly, though not enough for him to snitch on English Jim Stuart. His good conscience extended only as far as name-dropping a good attorney for Berdue to employ, and privately plotting to burn the town if Berdue hung for his crimes. His refusal to violate omerta proved his downfall. His loyalty to English Jim was not reciprocated when English Jim Stuart rattled off names with the likely mindset that he would be damned before letting Samuel Whittaker stay in Mary Hogan’s bed.

The Vigilance Committee voted to hang Jim Stuart. They built a makeshift scaffold on the wharf where he was caught and led him to the gallows within two hours of his extrajudicial conviction. English Jim treated his fate with blase indifference up until the last minute when, according to a witness, he had to be prevented from collapsing by two guards who forced him up and underneath the gallows. Unlike Jenkins, his death was swift. The force at which his body was hoisted broke his neck and his hat fell to the deck of the ship while his body swung, the breeze blowing his hair over his pallid face.

Above: The hanging of English Jim Stuart

The Committee proved timely in delivering the news of Stuart’s execution to Yuba County. Berdue was released, cleared of all crimes. The Vigilance Committee raised funds to cover the legal fees Berdue acquired while attempting to prove his innocence. Berdue was less successful in his efforts to receive official compensation from the state. In January 1853, the state denied his request for $4,000 under the reasoning that it would cause a precedent that would “exhaust the entire revenue of the State.” Continued the state, “In society it too often happens that the innocent are wrongfully accused of a crime. This is their misfortune, and the Government has no power to relieve them.”

In other words, innocent men are executed all the time. C’est la vie. Shit happens.

THE PEOPLE VS. THE GOVERNOR OF CALIFORNIA

Samuel Whittaker and Robert McKenzie were arrested and tried by the Committee in August of 1851. Their execution wasn’t as swift as the previous two. By this point, vigilante activities in San Francisco had become a major political issue that attracted the attention of California state Governor John McDougal. A political rookie from Indiana, McDougal previously served as Lieutenant Governor. Upon being nominated for the position of Lieutenant Governor, he remarked “I reckon I’ll take that. I don’t believe anyone else will have it.” Such a statement was reflective of the Governor’s idiosyncratic personality, the kind of personality the likes of Jon Stewart and The Onion would have a field day with if McDougal was alive today. Notorious for beginning every proclamation with “I, John McDougal,” he was jokingly referred to as “I, John.” Despite his early popularity, McDougal’s tendency to binge drink and gamble with fellow politicians made him difficult to take seriously. Even worse for his image was his combative personality. He had tendency to turn the most minor bureaucratic spat into a battle, a liability in a career where likability to voters and colleagues matters far more than efficacy at one’s job.

Above: “I, John” McDougal, Governor of California in 1851

It was with this combative, control-freak personality that John McDougal made his fight against the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance. An official proclamation condemned the lynching of John Jenkins and English Jim Stuart for its disregard of municipal power and due process, and he was prepared to reinstate state authority over San Francisco before the Committee executed Whittaker and McKenzie. He ordered law enforcement to remove the two Australians from their custody at the Committee headquarters on Battery Street and place them in the city jail to await a proper trial. On August 21st, deputies of the San Francisco Sheriff and famed former Texas Ranger Captain John Coffee Hays took Whittaker and McKenzie into custody without a fight from the Committee.

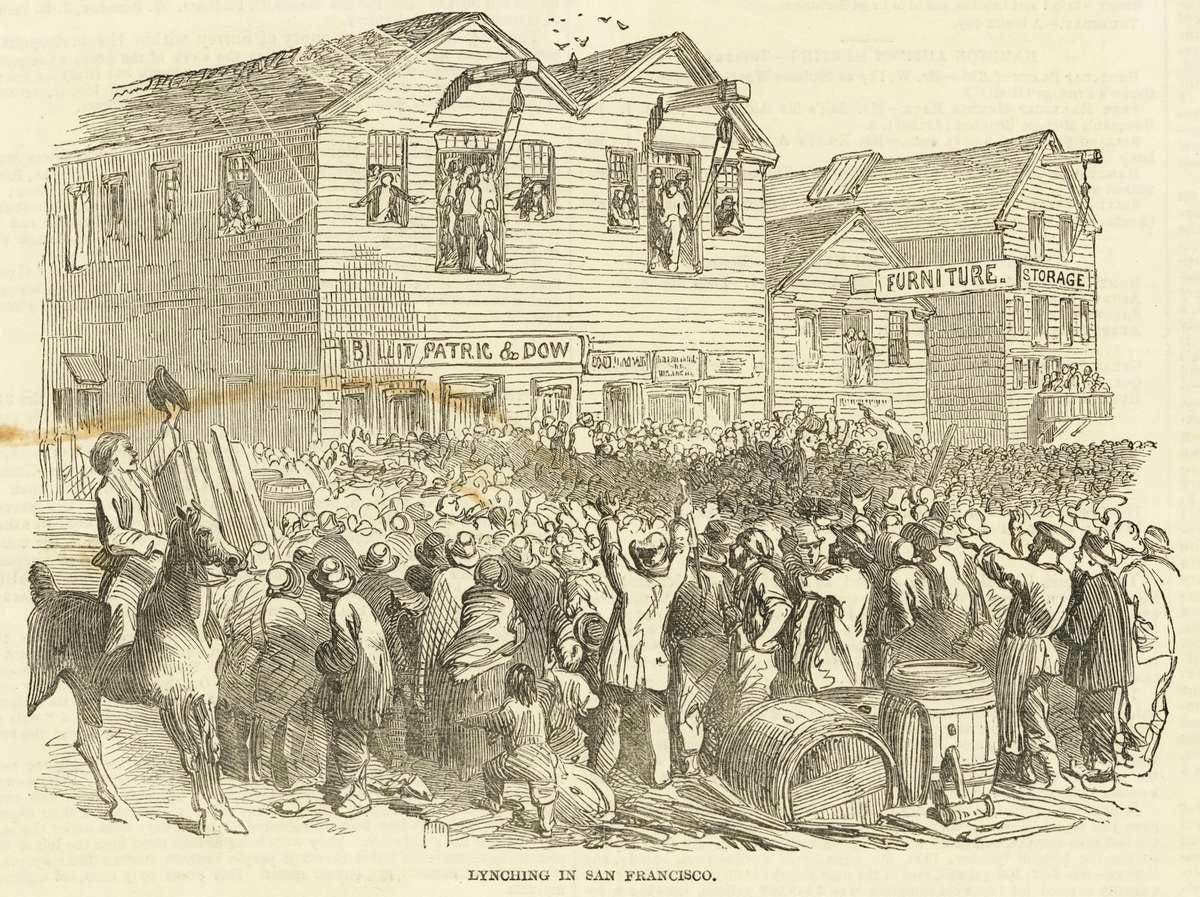

Three days later on August 24th, armed members of the Vigilance Committee stormed the jailhouse. Overpowering the guards, they recaptured the prisoners and dragged them to the Committee headquarters. Tying nooses to two beams above the windows of the headquarters, they hung Whittaker and McKenzie by the neck until dead while a crowd numbering in the thousands watched and cheered on the actions of the vigilantes.

Above: The lynching of Whittaker and McKenzie

FROM THE ASHES

By the time the Vigilance Committee officially disbanded in September 1851, they had executed four men, deported fourteen back to Australia, forced another fourteen to flee, handed fifteen to the proper authorities, and flogged one man. All said and done, the Committee was successful in quelling the more violent activities of the Sydney Ducks. But Sydney Town remained a hot spot for vice and would remain so for many decades after it ceased to be “Sydney Town” and became known as the Barbary Coast, a status it would retain until the Red Light Abatement Act closed down the last Barbary Coast brothels in 1917.

John McDougal’s failed stand against the Vigilance Committee may have been the final straw in a series of embarrassments the Governor created for California’s Democratic Party. Up for re-election that year, the party refused to nominate him and instead nominated State Assemblyman John Bigler. In contrast to McDougal’s support for Chinese immigration, calling them “one of the most worthy classes of our newly adopted citizens,” Bigler ran on an anti-Chinese platform and won the closest gubernatorial election in California history. McDougal was a dueling enthusiast who opposed outlawing pistol dueling on the basis that the problem would sort itself out naturally when all duelers killed each other off. True to his stance, McDougal engaged in a pistol duel with a newspaperman a mere four days after leaving office. He injured the newspaperman and was arrested by San Francisco police when he attempted to duel another opponent who had insulted him. Time wasn’t kind to McDougal. His political career in shambles, his drinking intensified and he made multiple suicide attempts before dying in 1866 at the age of 48. His remains one of the youngest deaths of a California Governor.

Innocent Australians didn’t suffer the same indignations that Hispanic and Chinese Californians faced when confronted with vigilante justice, but the atmosphere of terror compelled many to leave. The discovery of gold in Victoria, Australia attracted many Aussie 49ers back Down Under to take part in the Victoria Gold Rush. Those Sydney Ducks who remained in California fled San Francisco for the smaller towns in gold country, well beyond the reach of the Vigilance Committee where they could continue to operate as highwaymen. With the state’s attention increasingly turned towards Hispanic bandits like Salomon Pico and Joaquin Murrieta, the remaining Sydney Ducks laid low while absorbing themselves into various criminal gangs.

At least four of them joined the gang that would make the fatal mistake of assaulting a three-man party in the final weeks of 1854.

Coming Next: Jonathan R. Davis’ fateful stand-off against the remnants of the Sydney Ducks in The Last Man Standing Part III: And The River Ran Red