The Last Man Standing Part I: Wayward Sons

How a Southern Son of Privilege and Ex-Cons Down Under Landed in California to Exchange Bullets

When he passed away in January 2024 at the age of sixty-three, sculptor and special-effects artist Michael Trcic left behind an impressive portfolio of work. Reputed for his dinosaur models, he served as the lead animator responsible for the iconic Tyrannosaurus Rex in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 movie Jurassic Park. But while his movie career included a wide range of credits - from Terminator 2 to Discovery Channel Dino docs - from his studio in Sedona, Arizona he was a prolific sculptor of the American West. His subjects were fairly typical, ranging from Apache warriors to high country cowboys. One of his sculptures stands out for the story it tells. It features a man in motion, armed with two Colt Navy revolvers and is titled “One Man With Courage Is A Majority.”

Above: “One Man With Courage Is A Majority” by Michael Trcic (courtesy of the artist’s website)

The man in question was named Jonathan R. Davis. The sculpture commemorates the remarkable event in which Davis, armed with only those two revolvers and a Bowie knife, held his own against a band of fourteen highwaymen that included members of the most notorious gang in 1850s San Francisco, the Sydney Ducks.

American action movies exaggerate an individual man’s capacity for efficient violence against greater numbers. John McLane single-handedly slaughters his way up and down the Nakatomi Plaza building. Rambo re-fought and won Vietnam. Martial artists take on swarms of ninjas for hours. Celluloid combat rarely shows a one punch KO to primary characters. It never shows the short stretch of time one’s stamina allows a fighter to remain in constant motion. It rarely shows the brutal reality of an effective fighter overtaken by strength in numbers, a larger opponent, or simple bad luck luck.

It almost certainly never shows the reality that neither Hollywood nor your average NRA advertisement obscures about gun fights: the average person’s inability to keep a calm under fire. Even the experienced shooter is only a mistake away from death.

All of this is to say that when one man actually manages to hold his own against multiple opponents, it isn’t simply unusual. It’s anomalous. It’s almost unbelievable.

But that’s exactly what Jonathan R. Davis did when he was ambushed in December 1854. Fourteen men ambushed Davis. When the smoke cleared, eleven of them lay dead.

“No one, not even you, will remember if were good men or bad. Why we fought, or why we died.”

WHY WE FOUGHT, WHY WE DIED

History is filled with causes and effects. Disparate lives borne out of actions and experiences far beyond the memories of those involved collide with transformative - and often destructive - results. Two soldiers may face each other on the battlefield without ever truly comprehending the long chain of events that led to their final moments. Like many violent acts in the history of frontier California and in the wider Western US, Jonathan R. Davis' stand-off was a single small occurrence set against the larger backdrop of human history. It was an occurrence born from a nascent island empire’s need to dispose its undesirables on a colonized continent. Born from the wealth of slave owners. Born from the westward expansion of the United States into Mexican territory. Born from the California Gold Rush and the instability that followed.

Telling the story of the shoot-out without the full details of why a pastor’s son from South Carolina and a gang that included Australian ex-convicts even crossed paths in the first place would be like telling the story of the D-Day without explaining how Europe fell into another war, let alone why the US was even involved. It also doesn’t do justice to the people involved, or to how truly bizarre, chaotic, and colorful California was during its massive Gold Rush population boom.

Jonathan R. Davis’ standoff is one of the many lesser-known gunfights of the old west despite the fact that it is simultaneously the most impressive and the least believable. Holding one’s own against fourteen men without a scratch is standard fare for spaghetti westerns and Louis L’Amour. It runs contrary to probability. It flies in the face of the de-mythologized - which is to say, real - old west, the old west this entire Substack is devoted to chronicling.

But it is also the perfect embodiment of the old adage that the truth is stranger than fiction.

SON OF A PREACHER MAN

Monticello, South Carolina isn’t known for much these days. Its most famous native son is former Padres left-fielder Gene Richards. Four locations in Monticello are listed in the US National Register of Historic Places. Two of them are plantation houses that oversaw the cultivation of cotton by slave labor. One of these houses was owned by a family called Davis and built by the eldest brother of Jonathan Rutledge Davis.

Above: Davis Plantation in Monticello, South Carolina

Jonathan R. Davis was born in 1816, the fifth child of Jonathan Davis and Rebecca Kincaid. The elder Davis was born three years after the end of the Revolutionary War, the only son of a Continental Army captain. He joined the ministry as a Baptist preacher, rose through the hierarchy of the Southern Baptist Convention until he became the Vice President of the South Carolina Convention, and played a major role in the foundation of Furman University. But Davis’ income came not from Christ but from crops. Like all members of the Southern gentry, Reverend Davis was a landowner and slave owner. The contradictions in being a slave for God and enslaving men to earn mammon never occurred to him.

Reverend Davis’ other great feat was fathering children, though only nine out of the eleven kids - six boys and three girls - survived to adulthood. They affectionately called their fifth child, Jonathan Rutledge, “Jona.”

The archetypal middle child, Jona took after his brothers William and Franklin and pursued law as an adult. William abandoned his practice to enter agriculture like his older and eldest brother James had done. Franklin had the brains and grades to enter Yale. But the best young Jona could manage was the publicly funded South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina), where he joined a fraternity called the Euphradian Society and graduated in 1837 at the age of twenty-one.

The 1840s were unkind to the Davis family. Financial problems forced Reverend Davis off the Furman University Board of Trustees in order to oversee the financial affairs of his eldest sons. Jonathan R. Davis married in February of 1844. His marital bliss was brief. His wife Mary Ann Carter died by October of that same year. Two years later, debt acquired in order to keep his sons afloat resulted in the loss of Reverend Davis’ estate.

The loss of the estate caused financial chaos for the disintegrating family. Eldest son James was appointed by President James K. Polk to teach cotton cultivation to the Ottomans in Turkey and left the United States for Istanbul with his younger brother Nathan. William, the other brother to fail at planting, settled into mercantilism while Franklin switched from law to medicine and developed a deadly drinking habit. One daughter had died, another was married to the son of Furman University namesake Richard Furman, and the youngest was left to care for her aging parents.

Which left widower and - by the standards of his elder brothers - underachiever Jonathan R. Davis to figure out his future. With little to lose, Jona did what many lost young men do when faced with an uncertain future.

He went to war.

YOU’RE IN THE ARMY NOW

100,000 Americans served in the Mexican-American War. 75,000 of those men were irregular volunteers. Twenty-two out of twenty-nine admitted US states sent volunteers and of those twenty-two states, fourteen of them were slave states. However controversial the war was to some, it remained overwhelmingly popular in the South for the practical reason that the conquest of territory South of the 36° 30' Parallel meant the expansion - and therefore, survival - of slavery in the United States.

Above: The Battle of Chapultepec, Carl Nebel

The Palmetto Regiment was where South Carolinian volunteers like Davis flocked. It was named for the palm tree that adorns the South Carolina flag and commanded by former South Carolina governor Colonel Pierce Butler. They saw their first action during the twenty-day siege of Vera Cruz and participated in the overwhelming American victory during the Battle of Contreras, which forced the Mexican Army into a retreat. The following day after Contreras, the Battle of Churubusco saw the death of Colonel Pierce Butler. Butler was said to be carrying the US flag when he died, and that same flag was said to be the first US flag raised over Mexico City when the city was taken in September 1847.

The surviving officers and soldiers of the Palmetto Regiment were awarded medals with the names of the five battles they engaged in - Vera Cruz, Contreras, Churubusco, Chapultepec and Garita de Belen - engraved around the rim of the medal. Jonathan R. Davis was among those officers. Originally serving as a second lieutenant, by the time he was taken out of action from an injury sustained during the Battle of Churubusco, he had earned the rank of honorary captain for his battlefield valor.

Discharged in the summer of 1848, Davis wouldn’t stay long in South Carolina. With no family estate remaining, rewarded with land warrant for 160 acres that many Mexican-American War veterans sold - or were swindled out of - for a one time payment of $50, Davis did what many young men in 1849 did when faced with the possibility of far greater fortune abroad than at home.

He went to California.

I COME FROM A LAND DOWN UNDER

The colonial victory during the American Revolution created a peculiar inconvenience to the British government: the loss of their largest and most effective dumping grounds for prisoners.

18th-century London was horrifically overcrowded, deeply impoverished, and beset by petty and violent crimes alike. The enactment of the Bloody Codes that catapulted the number of capital offenses to a whopping 220 did little to deter criminality and soon the jails of London were as overcrowded as her streets. The situation reached such severity that decommissioned Naval vessels were used as floating prisons that dotted the Thames. An alternative was needed. America was the obvious location to transport the prisoners since it was larger than their island territories in the Caribbean, where previous political prisoners had been shipped. Before the American Revolution, around 60,000 British prisoners were shipped to the US as indentured servants.

Above: Prison hulks (decommissioned ships) in the River Thames, 1814

The loss of the colonies put an end to America’s status as the British Empire’s primary penal colony. With an explosion of prisoners necessitating further ships along the Thames, the British government needed a new vast landmass to dump their social undesirables. Luckily for them, they were in the process of colonizing a continent they referred to as “New Holland” and alternatively as Terra Australis, The Southern Land.

Australia.

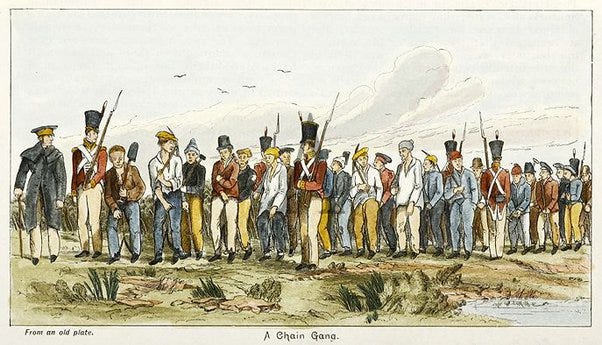

Between 1788 and 1868, Great Britain transported 162,000 prisoners to Australia. Though a small handful were guilty of serious felonies like rape and murder, the overwhelming majority of prisoners were petty criminals. 1 out of 7 were women. A small but notable minority of all convicts sent to Australia were political prisoners, including Irish rebels. After seven years, most prisoners were granted freedom with the option to either return to Britain or remain in Australia and join the growing settler population.

Above: See Title of Drawing

Although nominally granted equal rights, emancipated prisoners were poorly regarded by free settlers in Australia. Governor Lachlan Macquarie would appoint emancipated men to prestige positions to the chagrin of those who considered the large presence of ex-cons in Australia a stain on the colony. A growing anti-transportation movement saw indentured prisoners as both a security threat and a threat to paid labor. Under pressure from anti-transportationists and an economic downturn in the colony, prisoner transportation temporarily froze in 1846 as Australia received a large influx of settlers from famine-stricken Ireland.

News of gold in California reached Sydney in December of 1848. By 1849, nearly fifty ships bound for San Francisco had left Australia. The Australian migrants were atypical Forty-Niners. Most traveled as family units seeking the abundance of work opportunities offered by the impending population boom in California, and most were overwhelmingly of Irish origin or descent. A sizable number were single ex-cons whose experience in the penal colony did little to rehabilitate them. Typical of the Australians Forty-Niner experience was how few of them struck rich in the gold fields. Most stuck to San Francisco, and the Aussie population coalesced south of Telegraph Hill between Broadway and Pacific Avenue in a neighborhood that became known as Sydney Town.

Below: Ships entering the San Francisco Bay, painting by David Thimgan

Coming Next: An Aussie gang’s crime wave sets the streets of San Francisco aflame, an innocent man is bound for the gallows, and hard-drinking governor clashes with vigilantes in The Last Man Standing Part II: Sydney Town