Bring Me The Head of Joaquin Murrieta Part IV: The Brothers Feliz

The Fraternal Crime Spree Where Joaquin Murrieta Made His Bones

“The world in which you seek to undo the mistakes that you made is different from the world where the mistakes were made. You are now at the crossing. And you want to choose, but there is no choosing there. There's only accepting.”

-Cormac McCarthy

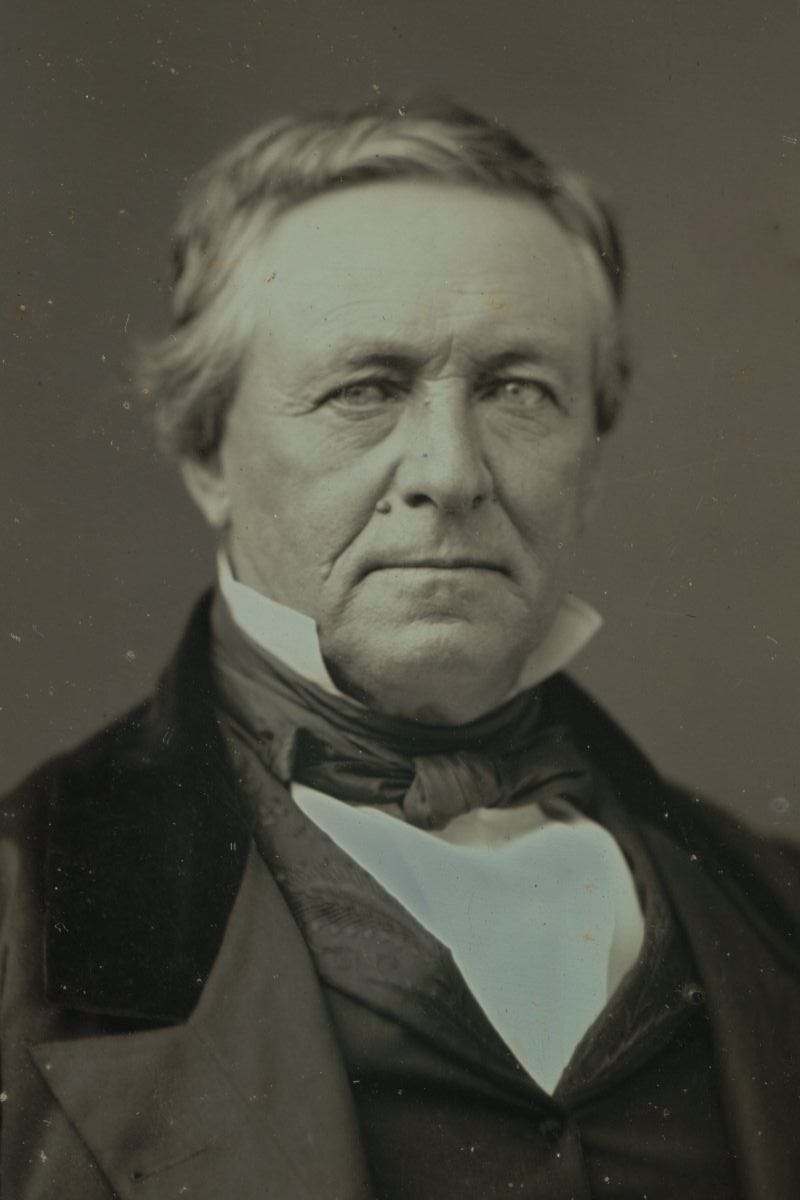

John Marsh claimed to be the first person to practice real medicine in California. He arrived early in 1836, presented local Mexican authorities with his Harvard degree. They never questioned the document. Since they couldn’t read the Latin the alleged degree was written in, Marsh was granted permission to open a medical practice. He charged exorbitant rates that made him wealthy enough to travel to northern California with $500 in his pocket and an aim to join the landed gentry. Ever the social climber, he converted to Catholicism to meet the legal requirement that all landowners be Catholic and purchased Rancho Los Meganos.

Rancho Los Meganos enveloped contemporary Brentwood in Contra Costa County. It was situated at the confluence of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers close to the coast, an idyllic settlement for a man on the make. Marsh was the typical California transplant, a man on a mission of reinvention. His previous wife died after journeying while pregnant in order to reunite with her distant husband. He chose to leave his son Charles in Illinois. He found himself a fugitive after he was caught selling weapons to Plains Indians. California meant a new start. California meant leaving hucksterism behind, joining the better classes. He ascended into the life of a ranchero and continuously expanded his property until he owned 40,000 acres and thousands of cattle at the time of his death.

Above: John Marsh, circa 1852

He was not a benevolent baron. The wages he paid his vaqueros were notoriously low. He feuded with a starving American immigrant family after they mistakenly killed one of his best work oxen for food. His ambition was ruthless and it encouraged his political duplicity. He recognized the growing distrust by the Mexican authorities towards Americans like him and realized the necessity of an American government in California to protect his interests. He wrote letters that promised paradise in California to any settlers willing to make the journey and housed and fed American immigrants who passed through his land. He infamously and inadvertently led to the unseating of unpopular governor Manuel Micheltorena by challenger Pio Pico when he convinced Americans on both sides of the conflict that fighting each other was folly. The loss of American riflemen led Micheltorena to be grossly outnumbered by Pico.

By 1850, Marsh had lived in California for fourteen years. He experienced Indian wars in the Midwest, escaped the law, and aided in the engineering of the American revolt in California. For as much life as he had experienced, little prepared him for the early winter of his fourteenth year in the new state.

December 5th, 1850. Marsh welcomes a lone traveler who claims to be an Argentine horse trader. The strangers spends the day in Marsh’s adobe. One imagines they spend the day discussing horses and the political day-to-day of California while Marsh flaunts his wealth as a cattle baron. The stranger leaves. Marsh thinks nothing else of the man. Such strangers coming and going is the life of a wealthy rancher.

Evening: twelve riders descend on the rancho. They move fast, armed with lances, Colts, and knives. They subdue the servants before the underpaid laborers can put up a fight. Marsh, earlier a welcoming host, becomes the prisoner to his former guest. They tear the adobe apart for anything of value and come across an American guest they failed to subdue, a Mr. William Harrington. Call it sadism, call it self-preservation against a Yanqui who might try to play hero, they treat him to a thrust of the lance, the Yanqui earning the toro treatment by the matadors. When eight stabs don’t do the trick, they euthanize the poor bastard with a bullet.

Above: Claudio Feliz’s evening raid on John Marsh

They make off with $300, gold watches, and a small armory’s worth of firearms. They leave John Marsh with the corpse of Mr. Harrington and the knowledge that he had just hours hosted and enjoyed the company of the man who robbed him, Claudio Feliz.

They didn’t keep a low profile very long. Ten days later they stormed the San Jose ranch of an American named Digby Smith. Compared to Smith’s fate, Marsh was lucky. The raiders tied Smith to a chair and caved his head in. Another victim had their head split with an ax. The cook was beheaded. They stole $1500 worth of goods, burned down the ranch, and fled into the winter night.

MEANWHILE, BACK AT THE RANCHO

Anastacio de Jesus Chabolla was a native son of California. His father was a soldier in De Anza’s expedition through the southwest and he followed his father’s footsteps in the military. He fathered seven children and was granted a 38,000 acre landholding, Rancho Sanjon de los Moquelumnes, before his fortieth birthday. Chabolla’s large fiefdom was his pride that he fiercely defended. Rancho Sanjon was located inland south of Sacramento, vulnerable to thefts by starving Indians from the mountains. So when the news of Digby Smith’s nearby murder reached him, he wouldn’t have taken the threat lightly.

He had other reasons to fear for his life. The year prior, the remains of an American man had been found in Santa Clara and identified as a missing pioneer named Edward Pyle. Pyle was one of the rescuers of the Donner Party who married a surviving member before vanishing in 1848. Pyle’s father heard a rumor about the fate of his son and the whispers led him to a nineteen year old ranchero named Antonio Valencia, a nephew of Chabolla.

Pyle led a vigilante party who captured Valencia and detained him in a nearby house until the arrival of the alcalde and sheriff. Valencia confessed immediately to the killing. How willing that confession was depends on how much benefit of the doubt you would be willing to grant vengeful vigilantes horny with bloodlust. Valencia claimed he and Pyle engaged in a horse race that he won and that resulted in the injury of Pyle and his prized horse. Fearful of retaliation from the angered American, Valencia said he killed him. Valencia insisted the killing wasn’t his idea. He claimed remorse for the murder. He claimed he was advised to murder Pyle by an uncle who warned him that the Yanqui would come back to kill him.

He claimed that his dear uncle, Anastacio Chabolla, had instructed the youth to kill Pyle.

Valencia was found guilty in a fast and unofficial trial. He was kept chained in the house in lieu of a jail secure enough to keep vigilantes from breaking in and lynching him and he was hung for the murder of Pyle. It wasn’t enough for the Americans. Pyle’s father and his sympathizers wanted absolute justice. They wanted Chabolla to swing. Chabolla was arrested and detained, but the court system didn’t act fast enough for the Americans who organized two separate lynch mobs that were unsuccessful in granting Chabolla an early execution. The judge released Chabolla; a dead criminal’s feverish testimony was considered insufficient evidence. It didn’t change the fact that the elder Pyle and his boys had all but tried and convicted Chabolla in their hearts. All that remained was to carry out the unsanctioned sentence.

Chabolla had every reason to expect that they would make an attempt on his life. Anglos in frontier California neither forgave nor forgot what they considered abortions of justice. California’s court system was in a state of transition from Mexican to American law. Official law enforcement often consisted of little more than a sheriff and a town marshal. With no faith in the weak criminal justice system, lynch law prevailed. Wary of sharing his wayward nephew’s fate, Chabolla knew he would need to watch his back for the rest of his life.

The ferocity with which he was willing to defend his life and property would be a lesson learned for those who attempted to violate both in February 1851. Claudio Feliz and his gang attempted the same bandit blitzkrieg they had utilized to great effect the previous year and found the adobe heavily guarded. Chaballo and his vaqueros held their ground against the onslaught and forced Feliz and his gang to retreat. The countryside close to the Bay was too populated for the ambitious outlaw. The failure to capture Rancho Sanjon was a wake-up call to the young man that his methods would end at a short rope like Antonio Valencia. He fled across the valley, returned to where his career began, Gold Country. He would be far from well-guarded ranchos, where he could wait along the road while men carried cash or gold in their purses and where a body could disappear without anyone around to hear the gunshot…

IF IT BLEEDS

Warning: A rant ahead.

There’s a question often repeated regarding the historiography of the American West and it's a question I’ve come to dislike:

“Just how wild was the Wild West?”

Above: “Gunfighters” by esteemed western painter C.M Russell

In the efforts to correct the long mythologizing and propagandizing of the old west, there has been a tendency to overcorrect, to swing from one generalized hyperbole to another. It’s generally taken the form of the suggestion “the west wasn’t actually that wild.” It’s necessary to push back against falsehoods and exaggerations when examining history. But reducing the question of violence in the American Frontier to a question like “how wild was the Wild West” becomes problematic for two reasons:

What does one mean by “wild” and what does one mean by “west”?

(Before you unsub and close this tab in aggravation, bear with me: this isn’t just pedantry, there will be a point to this).

When we talk about the American West, we are describing the largest stretch of land in the contiguous United States, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast, from the Canadian border to the Mexican border. When we talk about the “old west”, we’re discussing over a century of settlement and expansion, from the Louisiana Purchase to the statehood of Arizona and New Mexico in 1912. Add the century or more of Spanish and French colonization, throw in the centuries of pre-Columbian history and the historical boundary for what one considers the “old west” expands. The result is not a single “west” but “many wests”, which developed with variation according to the time and location of settlement. California in 1880 looks different than Arizona in 1880 looks different than Wyoming in 1880. None of these regions were culturally or economically monolithic during their period of Americanization.

Secondly, the “wildness” of the “wild west” was contingent on the circumstances of each region and the time of settlement. Violence has been emphasized over all other aspects in our cultural understanding of the old west for the same reason the nightly news loves car crashes and gangland shootings: if it bleeds, it leads. No one wants to hear about the domestic affairs of Tombstone, they want to hear about the OK Corral. For the purposes of drama, few traditional westerns focused on fully-developed towns with functioning criminal justice systems, low murder rates, and more than one school or church. They focus on transitional settlements where rustlers run rampant and where the Good Citizens (™) look to the gun-slinging stranger to save them.

For all the exaggerations in our popular culture, it cannot be mistaken that the frontier was a violent place. Frontiers by their very nature are borderlands beyond which the arm of the state has little to no real reach. Settler colonialism by its very nature requires violence to force displacement. The American West was the sight of mass displacement, forced starvation, and the execution of indigenous nations. It was a place that initially attracted young men searching for fortune and glory and usually fueled with the tempers and passions that drive the young and stupid. Outside of certain situations, the west was never “lawless” in the most literal sense of the word, but “the law” often meant little more than vigilance committees who acted swiftly to impose their prejudiced justice against groups and individuals they deemed guilty. The violence perpetrated in the American West rarely resembled high noon duels. It could be as pedestrian as a drunken brawl. A dispute among neighbors. Domestic violence. Violence was very often dealt out by those claiming to represent authority, be they law officers, vigilantes, or private agents.

These periods of instability were by no means permanent. They were a product of transition, settlements shifting from tent town mining camps to an official municipality in a region with weak courts to settle even basic civil disputes. The reputation many towns received as “toughest town in the west” was a reputation earned in the span of the first few months to the first year of the town’s founding. Between the arrival of the first young impetuous men to the eventual arrival of families hoping for a permanent settlement, between tent brothels and hanging trees to schoolhouses and firearms ordinances. California during the Gold Rush was a period of similar transition.

All of this is to say that as heinous as the actions of Claudio Feliz seem to our sensibilities, they were not unique and they did not occur in a vacuum. The same year of his crime spree, a US Army detachment murdered two-hundred Pomo Indians in retaliation for the deaths of two American settlers who had been enslaving and brutalizing the Pomo with the full legal backing of the state government’s passage of the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians. It was one of a number of massacres committed by the army or state militias against indigenous Californians in that year alone. State violence against the indigenous was far from the only occurring in California. Nativist gangs in San Francisco harassed Mexicans and warred against Irish-Australian immigrants. Pro-slavery Southerners in Los Angeles forced the first city marshal out when he bothered to investigate attacks on black men in the pueblo. Beatings and brawls became a common occurrence in Los Angeles’ red-light district Calle de los Negros. The memory of massacres done by Americans to Mexicans in Saltillo were fresh wounds salted by young veterans pumped full of jingoism and the thrill of war while others had no ideological or ethnic motive force for their violence beyond the reality that, like the oil workers who seek their thrills by raping native women in remote territories close to the Rez, they now had the freedom in a new land to act upon their basest impulses.

Claudio’s exact reason for turning to crime remains a mystery. In neither records nor legends is there any indication that such activity was partaken prior to migrating to California. His arrest likely dampened his future prospects. Locked in a Stockton jail, he likely met veterans of banditry. Like many contemporary prisoners who learn to become better criminals while locked away with lifers, he may have been instructed in the art of felony beyond the alleged theft of a few gold nuggets. His desperate escape did little to improve his diminishing chances of integrating into a peaceful life. The law had already taken the word of Anglos over the word of a Sonoran immigrant, and the Americans were driving Mexicans out of the mines at increasing rates. If he was going to do the time, he might as well do the crime.

But his crimes, as well of those Joaquin was accused of, were hardly the actions of a freedom fighter resisting Anglo occupation. His decision to attack a Californio’s rancho doesn’t square with the image of proto-Chicano patriot. There’s little real evidence that he or Joaquin shared their loot with the poorer among the large Hispanic community of California. Fast cash seemed the more likely motive than freedom.

The impulse to characterize Joaquin Murrieta, his in-laws, and many other similar bandits as quasi-revolutionaries is tempting and to a degree sensical. They faced hardship and discrimination in a country newly occupied as a result of foreign invasion. But the impulse is borne less out of the reality of their actions than the contemporary political implications they have, specifically out of a necessary need to invert the longstanding stereotype of the Mexican bandido. From Treasure of the Sierra Madre to For A Few Dollars More to Frito commercials, bandidos bearing sombreros and sarapes with bandoliers across their chests and a gold-toothed smile have dominated the popular imagination of Mexicans in the old west. The image exists to the understandable chagrin of many Mexican-Americans and it exists to create a slimy foreign “Other” in contrast to the masculine Anglo hero. The image has roots in the long list of well-known and oft romanticized rustlers and bandits who operated in California and along the borderlands in the late 19th century, as well as the propaganda push against Pancho Villa after his raids in New Mexico. These outlaws - Tiburcio Vasquez, Saloman Pico, Juan Cortina - were vilified, hunted, romanticized, and eventually rehabilitated as romantic Robin Hoods to their aggrieved nation.

Above: Italians playing the classic Mexican bandits in Sergio Leone’s For A Few Dollars More. Note the rogue Klaus Kinski on the left side of the frame.

This shouldn’t have to be said but: the large number of California bandits with Mexican origins is not the product of some sort of innate criminality in a community of people who were largely laborers and agriculturalists. Nor did they have a monopoly on criminality in California. Jack Powers, the Irving Gang, Rattlesnake Dick and the Skinner Brothers, the Sydney Ducks, Black Bart, the Dalton Gang, the Evans - Sontag duo, these are just a handful of the more well-known criminals in California who didn’t match the stereotype of the Mexican bandit. And what else can the militiamen and vigilantes who enslaved, raped, and murdered indigenous Californians be called if not bandits?

The irony is that the revisionist image of Californio outlaws as proto-revolutionaries often had its roots in the paranoid fantasies of Anglo settlers in the grip of a siege mentality. The summer the hunt for Joaquin officially commenced, newspaper reporters erroneously claimed that he had an entire militia of men bound for Baja California where he would raise forces. Such reporting existed to justify the eventual filibuster invasions of Mexico by men like William Walker. If Joaquin had an army at his disposal, would he not have captured small settlements like Monterey? Similar reporting from paranoid whites fearing a race war occurred four years later following the murder of Los Angeles County Sheriff James R. Barton by the Flores-Daniel Gang. Rumors swirled that Flores and Daniel aimed to massacre whites and lead the Californios in a revolt against America. The two outlaws never made that claim themselves. They never expressed revolutionary aims. Their alleged number of forty men was a gross exaggeration and according to Juan Forster of San Juan Capistrano, they robbed their fellow Hispanics with equal glee. Reality did little to quell these rumors, and Anglos in fear of revolt wantonly killed local Mexicans on the false whim that they were working with the gang. The early documentarians of California history kept the rumor alive and added colorful characters like femme fatales disarming the sheriff’s men in the dead of night, and it was revived by Chicano historian Rodolfo Acuna, seeing in the Flores-Daniel gang an archetype of then-contemporary Brown Berets. Ironically, it was a Californio detachment led by Andres Pico who did most of the successful legwork in bringing an end to the gang. If Flores and Dnaiel were really selling revolution, wealthy Californios like Pico weren’t buying.

Contemporaneously, reception to such men among Californios was mixed. While newspapers like El Clamor Publico disparaged men like Joaquin Murrieta as being little more than opportunistic bandits, there was a natural horror to the ease with which Anglos would prosecute and lynch their brethren. The hanging of Antonio Valencia horrified the local Californios who correctly recognized that the racist passions of angered Americans could turn against them and their sons at a moment’s notice. Whatever patriotic sentiments may have made many Californios sympathetic to men like Claudio Feliz and Joaquin Murrieta, there was a strong divide on whether or not to support them. If Claudio Feliz had an actual patriotic social conscience, it’s likely he would not have made the fatal mistake that brought an end to his criminal career.

FATAL MERCY

Claudio’s new method in Gold Country ran on the slogan so popularly associated with buccaneers: dead men tell no tales. His fourteen year old brother Reyes joined him and assisted in the robbery and murder of a Mexican prospector near Chinese Camp, California. Clearly Claudio did not qualify for older brother of the year. When Joaquin exactly joined is unclear. A horse thief named Teodoro Vasquez was arrested in November 1851 and hung the following January in San Jose. Between his arrest and execution, he gave a confession implicating the Feliz brothers and a “Joaquin Guerrieta”, a possible misspelling. If correct, his confession suggests Joaquin’s membership occurred no later than the fall of Vasquez’s arrest.

Meanwhile, Claudio remained occupied with his bloody business. He lassoed an American and his black servant off their horses and slit their throats for their gold. His gang killed a teamster and two travelers. They shot Yuba County sheriff Robert “Buck” Buchannan. The sheriff survived. His Mexican compadre was less lucky.

Time and consequences were catching up to Claudio quickly. They grew more ambitious and subsequently grew sloppy. They traveled across the valley to pay a visit to farmer and justice of the peace John Kottinger, a founding father of Pleasonton, California. Presumably they aimed to charm him before robbing him, but his wife was suspicious and Kottinger forced them off. A later legend claimed Joaquin visited the property and was so distracted by Kottinger’s lovely wife that John slipped away to San Francisco to deposit all of his wealth before the bandit could rob them. It’s highly suspect that Kottinger would allow a man he suspected of being a notorious thief to be alone with his wife for more than a minute. Clearly Kottinger did not qualify for husband of the year.

Claudio and his gang were fairly youthful - Joaquin may have been the oldest at twenty-one - and the carelessness of youth would nearly be their ruin. Reyes Feliz visited a mining camp with two guns proudly hanging from his hip. Columbia constable John Leary recognized the guns as having been stolen and promptly arrested the teenager. Claudio and the gang organized a hasty rescue effort along the road to Columbia where young Reyes was being transported by Constable Leary and three deputies that included future Tuolumne County District Attorney Caleb Dorsey. The gang ambushed the party on the road but found themselves equally matched. One of their ranks was killed by a bullet from the Constable’s party and Claudio took a wound that slowed his escape. Reyes managed an escape amid the confusion. Claudio was less lucky. Leary approached Claudio and aimed his revolver at his head, prepared to murder him in cold blood. Caleb Dorsey’s intervention spared Claudio the indignity of a point-blank head wound.

Despite the arrest, Claudio’s luck only improved. His responsibility for his many murders had yet to be discovered by Tuolumne County authorities, so he was only charged with attempting to spring a prisoner and for firing at a law officer. Claudio retained his savior Caleb Dorsey as his attorney. The Harvard man convinced the all-Anglo jury to acquit Claudio, a bold act of lawyering for a man who had once been at the other end of Claudio’s gun. While Joaquin and Feliz went their own way, Claudio returned to his highwayman activities and robbed a Californio named Agapito. In an act of uncharacteristic mercy, he allowed Agapito to live.

His act of compassion proved mistaken. A proud native son of Monterey, Agapito took the insult gravely and it cost any protection that Claudio might have received from Californios. A Californio posse tracked him and his followers to the Salinas River and ambushed them. Claudio was killed in the bloody fight, killed at the whim of the one man he allowed to go free.

WHAT GOES AROUND

John Marsh and Anastacio Chabolla had the fortune to not meet their ends at Claudio Feliz’s hands. But fate waits for no one. They could only live in the world created by their actions and by the actions of other men.

Chabolla was found hanging from a tree in 1852. No one came forward and claimed responsibility. No one can look at the circumstances of his life and not help but wonder if Pyle or his sympathizers found closure for Edward’s murder with the aid of a rope.

Above: The Stone House of John Marsh

Marsh continued to live his life of extravagant barony. His robbery did nothing to humble him. He found no spare funds in his coffers to raise the wages of his vaqueros. He did have enough to upgrade his dwellings from a simple adobe to an elaborate stone mansion. His vaqueros were not amused. Three of his underpaid vaqueros ambushed him on the road between his land and San Francisco and killed him. Ten years later, one of the assailants turned state’s evidence against one of his comrades. It spared him the dime in prison the other man served. The third killer was never discovered, but he lived the rest of his life freed of the starvation wages that led Marsh to his grave.

WHAT’S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT?

Late April, 1852. An abandoned wagon train is discovered on the Mariposa road between the Tuolumne and Merced rivers. One hundred and fifty miles down the road lay the body of Allen B. Ruddle, a twenty-seven year old farmer, shot “three times through the head, body, and arms” according to the Alta California. Ruddle left behind parents and siblings. The exact identities of the killers were unknown beyond a brief description provided by the newspaper with no evidence to back the assertion up:

“We have reason for supposing the murder was perpetrated by Spaniards.”

Ruddle’s family was dissatisfied with the slow progress of official law enforcement and posted a private reward for any agent of the law able to kill or capture Ruddle’s murderers. The reward attracted the attention of a forty-two year old Santa Barbara deputy sheriff named Harry Love. Love was a veteran of the Mexican-American War and an accomplished army scout and explorer before arriving in California. It made him the most likely candidate for tracking the killers.

A later confession by Reyes Feliz provides the best chronology for what had occurred to the gang following Ruddle’s death. The gang at some point robbed twenty horses, which they drove south from San Jose towards the Tejon Creek to water and graze the horses. A group of Indian vaqueros, likely under the command of a former Mission Indian named Chief Zapatero, took some of the horses. John Rollin Ridge’s account of the event depicted the gang being stripped naked and bound by the Indians. Reyes’ account never made such a claim. Pursued by posses and already robbed of their loot, the gang split up before crossing the mountains into Southern California. In an event heavily dramatized by Ridge, Reyes was attacked by a grizzly bear. He miraculously avoided becoming a Sonoran Timothy Treadwell, but the attack left him bedridden and unable to join the rest of the gang on their southbound escape.

Harry Love pursued the tracks of Ruddle’s killers and found two men fleeing south towards Mission San Buenaventura. One was identified as Pedro Gonzalez. The other was unknown, but may likely have been Joaquin. Gonzalez was overtaken and captured while his unknown friend managed an escape. Love captured Gonzalez to lead him towards Los Angeles for a trial. Gonzalez’s fate was the sort of convenient set of circumstances that would make an Internal Affairs officer blush and Alec Baldwin smirk. According to an affidavit filed by Love, Gonzalez complained of thirst and Love led him on foot to a river to drink. On their walk, Gonzalez apparently charged at Love to knock him down and make a run for it. Love claimed that he was simply attempting to pistol whip him. Instead, his Colt Dragoon accidentally discharged and fired through Pedro’s skull. Such things just happen I guess.

Above: “Oh man, I just shot Pedro Gonzalez in the face!”

Few questioned Love’s sketchy account. Fewer mourned Pedro Gonzalez. It would not be the last time in Harry Love’s law enforcement career that he would kill men in mysterious circumstances.

ESCAPE TO LOS ANGELES

Joaquin Murrieta arrived in Los Angeles that summer and Reyes soon followed. Most of their stay in LA was a quiet affair. Joaquin gambled, drank, trained horses, and found a new lover. Los Angeles, then as now, was the perfect escape from an old life to become someone new. He mingled among the crowds of vagrants, vaqueros, gamblers, drunks, whores, mongers, peepers, prowlers, punks, and pimps. The Feliz gang was no more. They could keep their heads down in the new town.

By the end of the year, Joaquin would flee and Reyes would face the wrath of a vengeful lynch mob without anyone to rescue him.

Coming Next: How Joaquin and Reyes became connected to a notorious murder case in 19th-century California’s move violent community in Bring Me The Head Of Joaquin Murrieta Part V: To Live And Die In L.A.