Knight of the Razor

The Controversial Life of LA's first Black Barber, Pete Biggs

Few in Los Angeles mourned when the news of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination reached the dusty pueblo. Los Angeles was rebel central, a hub of Southern sympathy whose largely Southern Anglo residents hindered any real effort by the state to provide military support to the war. Years prior, a pro-secession parade nearly caused chaos and forced the hand of the military to maintain a close presence around the town. Tears of joy and howls of laughter were a more likely response than a half-mast flag, but the military would have none of it. Since the war began, local authorities clamped down on seditious expression in the pro-Confederate county. Everyone from lawyers to newspapermen were swept up, arrested, and made to plead insincere loyalty oaths to the union. When the president’s death hit the coast, commanding officer Richard C Drum, stationed near San Pedro, made his opinion about men celebrating Lincoln’s death clear:

“Such persons become virtual accessories after the fact, and will at once be arrested…”

Not everyone heeded the warning. The Saturday before the 25th of April, a prominent barber named Pete Biggs announced his ardent support for secession. Biggs’ exhortations were intended to goad a response from the army. The goading worked. The army arrested and detained at the Drum Barracks to the south near Wilmington. For added measure, Biggs was recorded as having tossed his hat in the air and encouraged his fellow Southerners in the pueblo who watched his arrest to let out “three cheers for Jefferson Davis.”

Such pro-Confederate sentiments were not uncommon given the large population of men from slave states inhabiting Los Angeles at the time. But the case of Pete Biggs is an unusual due to a very specific detail that confuses any modern observer and confused even those contemporaries who watched him cheer for the ardently pro-slavery president of the Confederacy.

Pete Biggs was a black man who had once been a slave.

PART I

Pete Biggs was one of eleven residents marked as “black” in the 1850 Los Angeles census, and the only listed in his own home who owned a business. By the time of his death in 1869, Pete Biggs would be regarded by memoirists as one of the pueblo’s most prominent residents. A barber, a businessman, and a gentleman who had carved out high status for himself despite the strong racial prejudices of the age. He did so with a mixture of social acumen developed from slavery and a willingness to cater to the biases of his patrons in ways that would strike many today as debasing, racial sell-out behavior.

The self-proclaimed “Black Democrat” (at the time, a term with strong pro-Confederate implications) was one of Los Angeles’ first black businessmen and one of the many prominent settlers who struggled for his position among the nouveau riche. His life defies easy categorization despite the immediate impulse to compare his bizarre political behavior to contemporary black right-wingers and fictional self-hating black men like Uncle Ruckus. It doesn’t fit into the pro-Southern propagandistic myth of the “loyal, happy slave”, nor does it quite fit into preconceived ideas of how a black man in the American frontier would react to the Civil War and the issue of Emancipation. Biggs left no memoirs and his internal opinions and struggles died with him. But the circumstances of his life, of the political life of antebellum Los Angeles, and of the harsh realities of being a free black man in a pro-Southern town could explain why a man who had experienced the horror of slavery would cheer for Jefferson Davis.

PART II

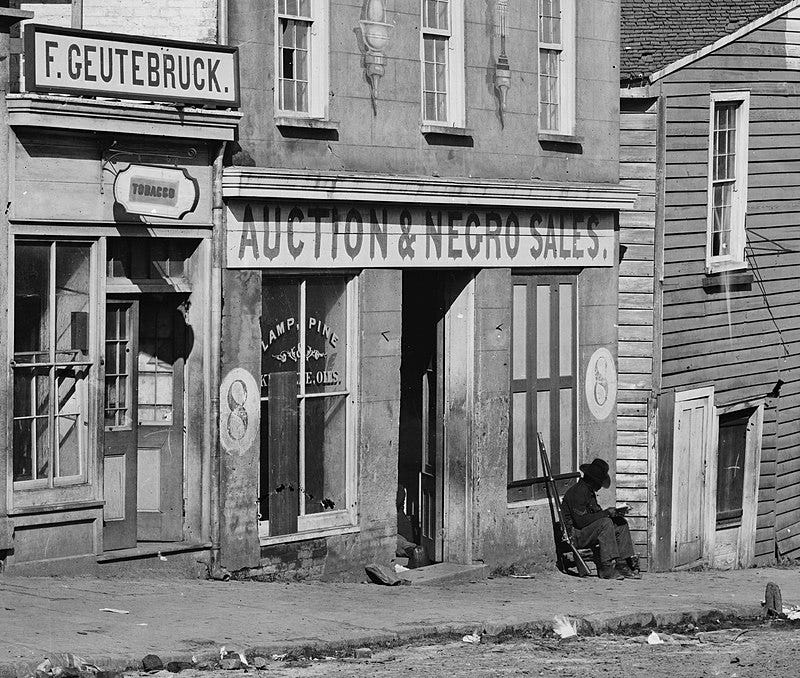

The exact date of Pete Biggs’ birth remains shrouded by the reality that birth records were not easily accessible and anyone who would have kept proper knowledge of Biggs’ birth - a mother or even an owner - would have been out of his life by the time he reached the age of reason. Like many born into slavery between the 1810s and 1860s, Biggs was subject to forced overland migration and frequent sale in what has been described as the Second Middle Passage, the transportation of slaves from the eastern slave states into the Deep South and Texas that occurred as a result of the cotton boom. Families were broken apart as siblings, partners, mothers and children were sold to separate owners to keep the internal slave trade flowing - it is from this period that the phrase “sold down the river” originates. In Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, the population of slaves increased by 27.5 percent every decade until Emancipation.

Above: A Black Union soldier reads in front of a former slave market in Atlanta, GA in 1864

As a result, locating the exact year and birth of Pete Biggs has never been accomplished. By his own reckoning, he was a Virginian by origin. An 1850 census listing him as being thirty-five years old suggested he was born in 1815. Ten years later, the census listed him as being thirty-nine years. Whether this anti-aging trick was the result of Pete’s inability to locate a consistent birth year, the carelessness of the auditors, or a desire to be a young man forever (or an older man earlier) is unclear.

Pete was sent from Virginia to Missouri and was soon purchased by a planter and Mormon convert named Rueben Washburn Middleton, who joined the LDS community in the Missouri settlement of Far West. Biggs spent enough time as Middleton’s slave in Missouri to have made the acquaintance of a young Baltimore-born lawyer named Benjamin Ignatius Hayes. Hayes would later land in Los Angeles, where he would serve for a decade as the first district judge of Southern California and where Biggs would be the first familiar face that Hayes would recognize upon his arrival to the pueblo. Middleton left Missouri for Nauvoo, Illinois at the behest of Joseph Smith’s declaration for his slave owning followers to free their slaves. Middleton instead sold Biggs to an army officer named Andrew Jackson Smith, fulfilling his religious obligation and ensuring a personal profit.

Biggs followed Smith through the Mexican-American War and overland to California. Smith had been placed in charge of the Mormon Battalion, and Biggs appears to have shared a decent level of privilege as Smith’s personal and unwilling attendant. A complaint by a battalion sergeant made reference to Smith sharing liquor intended for surgical uses with his “negro servants”. Biggs later appeared in courtroom records as having been accused of encouraging a private to steal $650 of gold and silver, a charge Biggs denied and provided an alibi against. While his alleged accomplices were imprisoned, Biggs’ punishment proved a legal quandary. He was a slave, not a free man, and any punishment inflicted on him by the army would be viewed as a violation of private property. As a result, a group of army officials who included a Monterey-based officer named William Tecumseh Sherman suggested that any punishment dealt to Biggs ought to be the domain of his owner, Andrew Jackson Smith. No record exists regarding Smith’s punishment of his slave.

Smith remained stationed in California throughout the duration of the post-war occupation with Biggs in Los Angeles. Towards the end of the occupation, Smith’s status as a slaveholder in California was thrown into jeopardy by the rush to statehood as a result of the Gold Rush. Southerners hoping to strike lucky dragged slaves with them to California in the hopes of using their labor in the gold fields. This tactic irked non-slaveholding miners, who argued that it would allow the Southerners an unfair advantage by being able to deploy multiple slaves at a time. It quickly became the chief topic of fierce debate during the 1849 constitutional convention of California. In a state of flux between Mexican law, which had outlawed slavery twenty years prior, and US law, which allowed slavery south of the 36°30′ Parallel, California faced a decision of whether or not to allow slavery into the territory. Southerners unsurprisingly voted in favor, arguing that a significant portion of California fell below the parallel. Northerners were split between abolitionists and those who cynically had no desire to be outworked by slaves to the benefit of their owners. By the end of the convention, slavery would not be written into the California constitution. By 1850, California would be admitted into the Union as a free state.

This did not end the practice of Southerners attempting to maintain slaves in California. But it significantly curtailed any legal institutions to protect their abilities to own slaves, such as a lack of slave catchers and public markets (the same cannot be said of the enslavement of California Indians, which was legally sanctioned). A number of Southerners had no choice but to either free their slaves or transport them back to a slave state to maintain them in bondage. Smith, reading the writing on the wall, left California for Missouri but he did not transport Biggs with him, perhaps wary of the cost. By winter of 1850, Biggs was a free man marooned in the City of Angels.

PART III

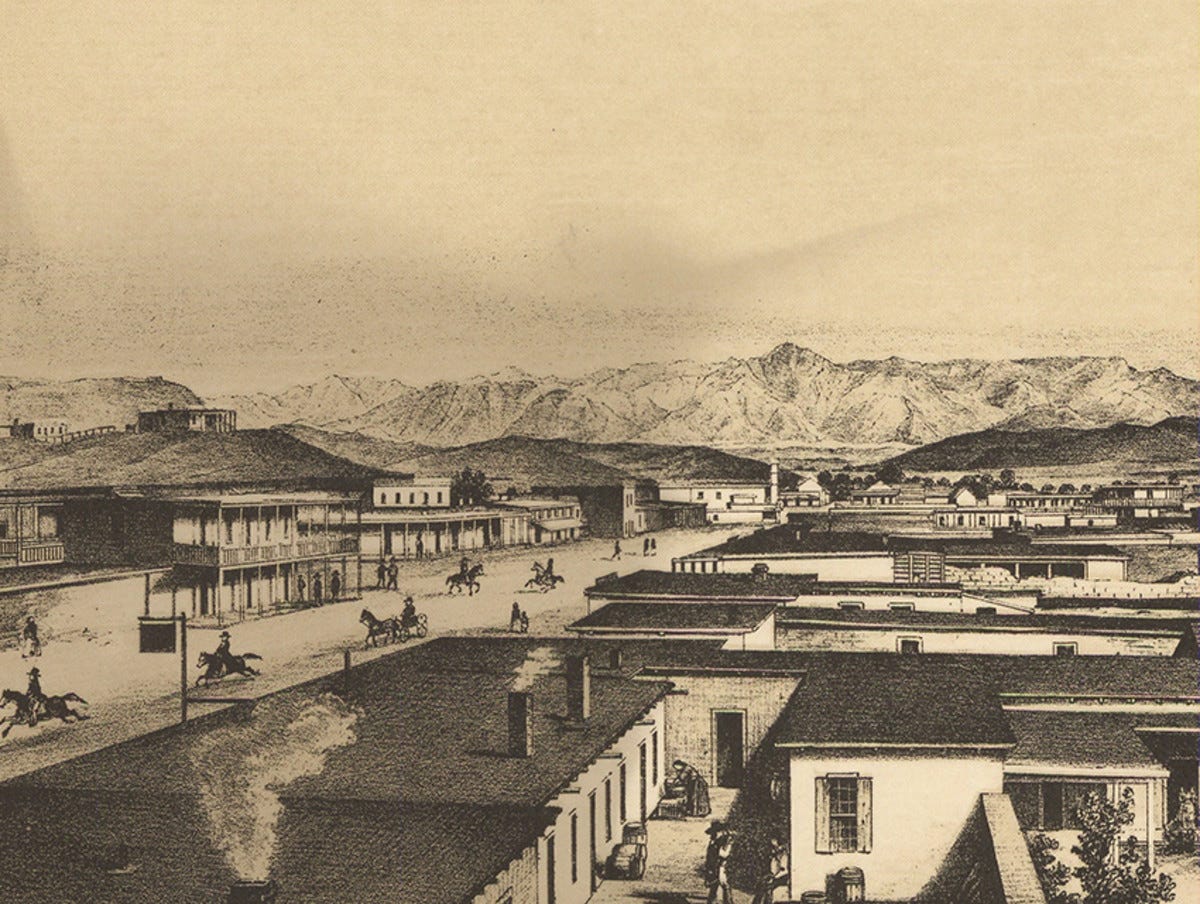

Above: Bird’s-eye drawing of Los Angeles in the 1850s

LA is a town with selective memory. Its self-mythology never extends before the advent of Hollywood and focuses on the town’s post-war transition from city to megalopolis. Such tunnel vision suggests that black history in LA begins with the first stirrings of a community on Central Avenue, but LA’s black history doesn’t begin with the Great Migration and it doesn’t even begin with Pete Biggs.

It begins with the founding of the pueblo in 1781.

Of the original 44 townsfolk or pobladores, 22 adults were listed in the census. Eight adults were listed as mulattos, of partial African ancestry. Two were listed as negros, black. The racial casta system of the Spanish Empire may have hindered social mobility closer to the core of New Spain, but there were little-to-no social barriers in place in the frontier of Alta California to insure a stratified society among the families of the pobladores. Referring to themselves as gente de razon, people of reason, the Californio settlers distinguished themselves by their assimilation into Hispanic culture and Catholic faith far more than by any sort of racial categories. Aiming to be viewed as social equals with those of pure Spanish blood, the mixed pobladores worked their way into a new landed aristocracy as rancho owners and into positions of government.

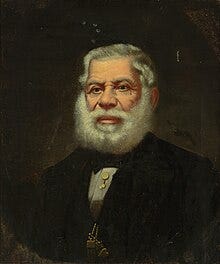

Among those of African ancestry was Pio Pico. The child of a soldier as many Californios of his generation were, Pico became a prominent member of Alta California’s liberal faction and played a major role in the secularization of Mission land when he served as a replacement for the deposed governor Manuel Victoria. He would repeat his gubernatorial ambitions by replacing Manuel Micheltorena (Manuel seemed to be an unlucky name for aspiring governors in California). Despite his deposition in the wake of the Mexican-American War, Pico would emerge from the war as one of the wealthiest men in 1850s California, owning half a million acres in land across the state alongside his brother Andres Pico, who owned the totality of the San Fernando Valley. Along with the other Californios living in Los Angeles at the time, Pico would be listed in the 1850 census as “white.” Postwar anti-Mexican prejudices notwithstanding, the efforts of the gente de razon to acculturate themselves from “mestizos” and “mulattos” into “Spaniards” had survived the transition into American California.

Above: Portrait of former California governor Pio Pico

What didn’t survive was the notion that a black man could so easily transcend his racial class into the ranks of the elites. Stricter views of racial division imported by the pueblo’s growing population of Southern whites created a stumbling block for ambitious men like Pete Biggs. Post Mexican-American War Los Angeles proved itself a violent settlement. Even the slightest hint of rocking the boat by any of the town’s eleven recorded black inhabitants would be met with swift retribution by the growing population of Southern whites. A freedman who attempted to sue for the return of mules taken by his father’s former master was assaulted in the streets. Three black men were forced into an adobe corral where whites began firing at the trapped men who escaped only by scaling the eight foot corral walls in desperation.

Despite these prejudices, Biggs saw in California what all migrants since have seen in the Golden State, a fresh start and endless opportunity. San Francisco suffered a severe rat overpopulation with too few cats to quell the scourge of rodents. Biggs began trapping and catching every cat within the vicinity of the pueblo with the goal of shipping them to San Francisco for a handsome price. Biggs briefly cornered the market in felines and made a small fortune that thrust him farther up the financial ladder of Los Angeles society. His feline fortune didn’t last. According to Horace Bell’s Reminiscences of a Ranger, Biggs spent much of his earnings in the abundant gambling houses of Los Angeles. The temporary nature of a rat problem that Biggs helped solve meant that if he didn’t want to fall into poverty, he needed to diversify his income and anchor himself to Los Angeles society.

As with the cats, Biggs kept his eyes out for a market to corner. For a service not offered in abundance in the pueblo that would require repeat customers. Biggs joined the long and fruitful trade that many black men of his age adopted and became a barber.

PART IV

The black barbershop is an iconic symbol of entrepreneurship and community with roots in the horror of slavery. Slave owners who relied on their slaves for personal grooming soon utilized their slaves’ skills as a means of extra income. Those who showed acumen as barbers would be allowed to migrate to a major city where they would be leased to a barbershop and allowed to practice their trade for pay on the condition of sending their owners a percentage of their income.

Although an unwilling arrangement, it placed those black men in the enviable position of being outside their master’s property far from the plantation fields and allowed them the privileged opportunity to earn an income. For many it provided a chance to purchase their emancipation from their owners and set up shop as barbers able to keep the income they made. By the middle of the 19th century, black men dominated the field of barbering. One-eighth of all black men with any considerable wealth were barbers.

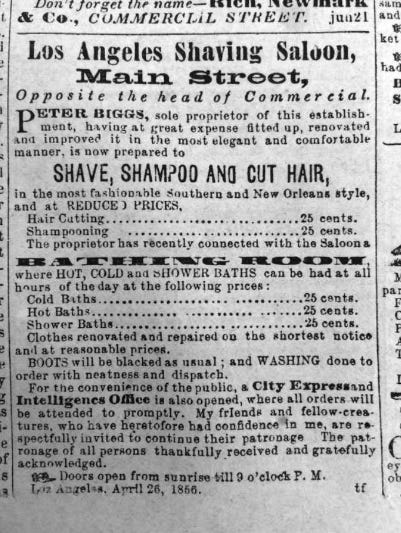

Above: A Black-run barbershop

Barbering provided emancipated black men in antebellum America a previously unmatched window of financial freedom in contrast to the lack of political freedom and civil liberties they possessed. Black barbers almost entirely catered to white clientele whom they engaged in conversation while straddling the fine and deadly line between confidant and subservient, a line that could cause lethal repercussions if they violated it. That shaving the beards of whites for a living kept them in a position of service made barbering a target of black intellectuals such as Frederick Douglass. “Make your Sons Mechanics and Farmers - not Waiters, Porters, and Barbers” Douglass insisted of black parents, arguing that service careers did little to elevate the social standing of black men. Douglass may have been correct that this career simply replicated the unequal relationship of slavery. But for most of the 19th-century even after emancipation, barbering remained among the few and most lucrative avenues of financial success for black men.

When and where Biggs learned the trade is unclear. Biggs lived in Saint Louis when Louis Clamorgan, one of the many wealthy mixed-race descendants of French explorer and landowner Jacques Clamorgan, owned and operated his own exquisite barbershop and bathhouse. His tenure as an attendant to Andrew Jackson Smith would almost certainly have resulted in him being tasked with shaving and trimming the officer’s hair. But Biggs’ possibly questionable skill as a barber - memoirist Harris Newmark described Biggs as being “by no means of the highest tonsorial capacity” - played less of a role in his decision to enter the trade than his keen eye for gaps in the market. When he opened his “shaving saloon” in 1850, he was the only English-speaking barber able to cater to Anglo clientele and the only barber able to socially and culturally connect with the increasing population of southerners on the basis of understanding their cultural mores.

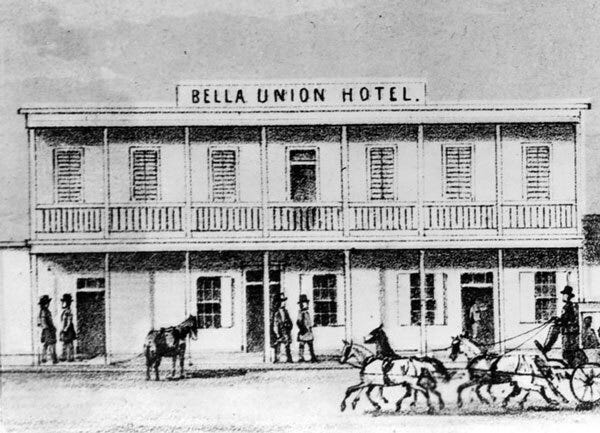

Whatever his “tonsorial capacity”, Biggs was a first-class businessman who understood perfectly how to cater to his primary customer base of Southern whites. Biggs opened his shop in a shack connected the the Bella Union Hotel, a prime location for new arrivals to receive a shave and a bath. He advertised his shop not only as “southern style” but “New Orleans style” to imply a level of urban sophistication not found anywhere else in the dusty cattle town and went to great lengths to ensure that Southerners distant from their home received a taste of Dixie in the experience of being shaven by and socializing with a black man. Biggs spared no expense in maintaining this experience and purchased a high-backed chair to distinguish his business as a first-rate barbershop. Baths soon followed, with boot-blacking performed on every customer in need as Biggs tirelessly worked from sunrise until 9pm.

Above: The Bella Union Hotel where Pete Biggs opened his barbershop

Biggs quickly became a major social fixture of Los Angeles life. Reuniting with former fellow Missourian Benjamin Hayes in early 1850, Biggs tasked himself with acquainting Hayes with every other Missourian in the pueblo. By that time, Biggs had anchored himself to Los Angeles society through a different method: marriage to a Californio woman named Refugio. A daughter soon followed and Biggs earned the benefit of social connections to the Hispanic population of town.

But upward marriage and financial freedom didn’t insulate Biggs from the racial codes imported by the increasing white southern population of Los Angeles. Biggs was placed in the dangerous position of navigating class mobility in a town where racial animus was often the rule.

An alleged incident in 1850 highlighted the danger that faced black men like Biggs who dared to straddle the divide. Biggs’ skills as an orator earned him the position of master of ceremonies for many Spanish fandangos. During one of these balls, a white man named Aleck Bell was spurned by a Doña Romana. Doña Ramona instead chose Biggs as her waltz partner. According to Reminiscences of a Ranger:

“This was more than Southern blood could stand, and out came Aleck’s Colt. The music was stopped and Aleck stepped up to Doña Ramona and inquired of her if she ‘preferred dancing with a nigger than to a white man.’ She replied that in this particular instance she did; that Don Pedro was El Bastonero, the master of ceremonies.”

Aleck Bell took that response about as well as one would expect a racist to and fired his revolver in the direction of El Bastonero. Pete Biggs fled out the door and vanished in the night. Not seen for days, Angelenos assumed Bell had killed him until Biggs sent a message from an unknown refuge promising that he would “keep his place” so long as he was permitted to return to town unharmed. It was a promise he would apparently keep with bizarre results.

How true the account is hinges on one’s willingness to take the storyteller Horace Bell - of no relation to Aleck - at his word. Bell didn’t live in Los Angeles at the time of the incident and frequently embellished his memory of the town’s wild 1850s. An 1849 report suggests a saloon had been shot up by a group of Southerners that included Aleck Bell with the motive that the owner had allowed dancing between black men and white women. Whatever the truth of the anecdote, it highlighted the racism of frontier Los Angeles and it depicted the precarious situation that an upwardly mobile black man like Pete Biggs would have found himself in.

PART V

Brushes with death aside, Biggs’ barbershop made him enough of a success to open another shop on Main Street. Being the only barber catering to Americans made him the acquaintance of virtually every Angeleno as did his gigs as a master of ceremonies for balls. Biggs’ ability to maneuver through Los Angeles society and his keen eye for expanding his earnings may have had a less savory side. When introduced to Horace Bell in 1852, Biggs suggested that he could connect Bell to local women not of “high class” but those women anxious to meet strangers with money to spend. Whether Biggs used his connections to procure women or whether he simply had the know-how to point Bell towards such the town’s prostitutes remained as unstated as whether or not Bell took the barber on his offer.

Biggs’ flaw as a businessman was that his entire barbering enterprise rested on the assumption that he would have the market cornered forever. Had Los Angeles not attracted a further influx of migrants this may have been possible. Competition from new barbers, whether black men or foreign immigrants, became an inevitability Biggs was not entirely prepared for.

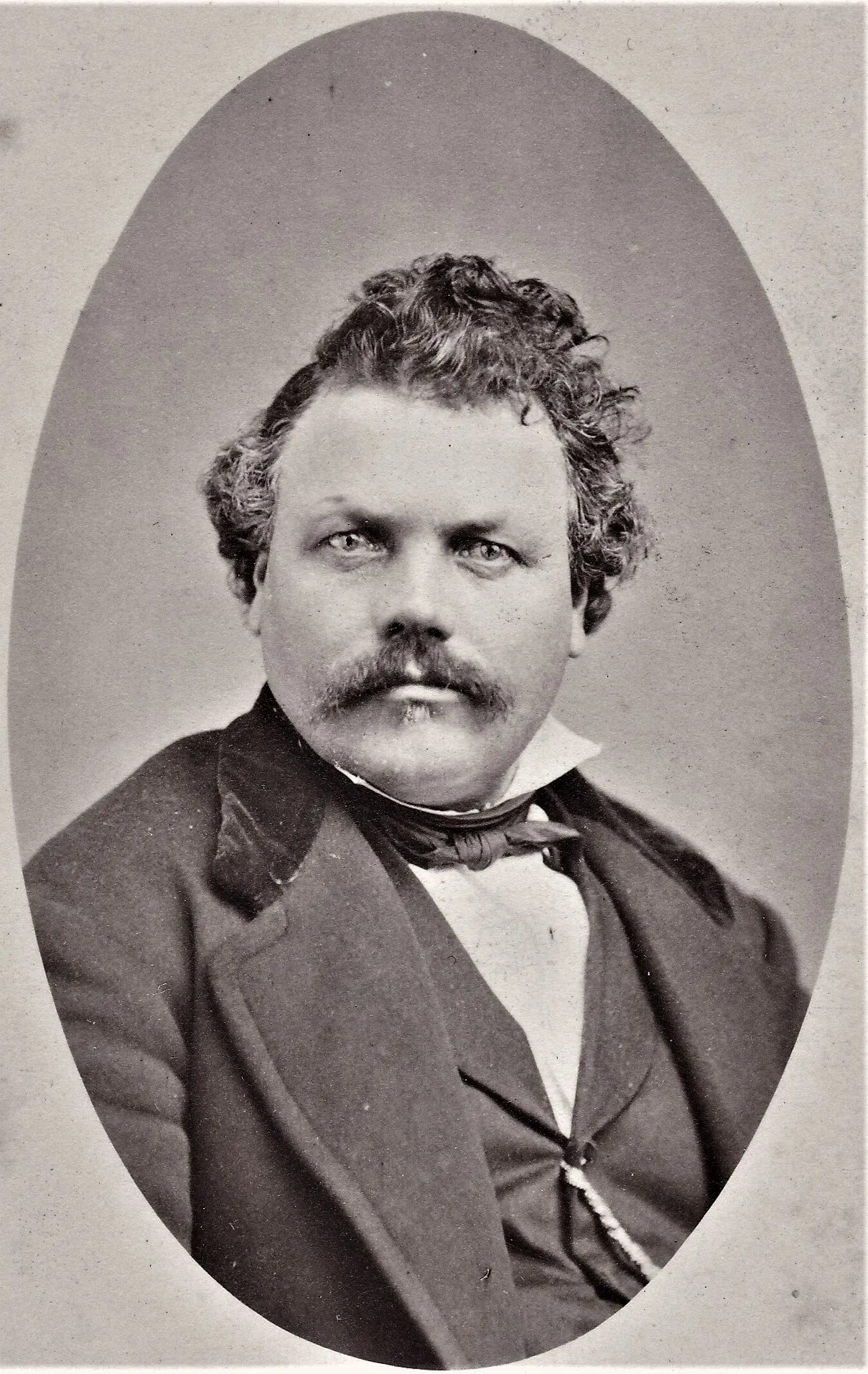

The toughest competition came in the form of a beefy Frenchman from Marseilles named Felix Signoret. Later an entrepreneur and active leader in the vigilance committee, Singoret arrived in Los Angeles around 1856. If Biggs’ skills as a barber were questionable, Signoret’s were indisputable. Such an occurrence was not unique to Biggs or Los Angeles where black barbers found themselves in the position of having to compete with white immigrants who poached a segment of white clientele perhaps more comfortable with even a non-Anglo white man than with a black man.

Above: A photograph of French barber Felix Signoret, Biggs’ business rival

No numbers exist counting how many potential or even former customers Biggs lost to Signoret. But the competition proved serious enough that Biggs soon slashed the prices of all of his services in half, from fifty to twenty-five cents in 1856. Ever savvy and capable of reading the writing on the wall, Biggs expanded his business ventures into the world of groceries when he purchased a space for his wife Refugio. The goal would be a general goods store selling fruits, vegetables, and the “raising, selling and buying of fresh poultry.” Their ambition extended to incorporating a coffee house and restaurant within the shop, perhaps making it the frontier equivalent of a Whole Foods.

The dream didn’t last more than a year before a fire damaged the store and possibly parts of Biggs’ nearby shaving saloon. The losses from the fire forced Biggs to lease out his Bella Union barbershop. The decision would come to bite him two years later when Biggs brought a lawsuit against a Mexican barber who allegedly prevented Biggs from taking residency in his own shop. The law prevented a black man like Biggs from formally testifying in court. But Biggs’ acquaintanceship with district judge Benjamin Hayes combined with Hayes’ established willingness to hear out black witnesses, such as in the Biddy Mason case, provided Biggs a chance at courtroom victory.

Biggs lost the case with $15 of legal fees. Although a popular citizen and a property owner, Biggs’ financial situation seemed grim in the face of tragedies and increased competition. Ten years after Biggs entered the barbering trade, six other barbers were registered in town. The slowly growing black population in Los Angeles spelled further potential for competition as barbering had become the most popular and lucrative profession for black men. If Biggs was to survive as a businessman, he needed a change of strategy.

Biggs began by seeking the financial aid of black businessman and community leader Robert Owens. A Texan who purchased his freedom, Owens had by 1860 become the owner of a livery stable and cattle operation lucrative enough to afford the services of ten cowboys. His home served as the center of Los Angeles’ small black community, hosting church services and political meetings. Owens went so far as to purchase most of Biggs’ barbering equipment for the apparent sole purpose of providing Biggs some income while Owens held onto Biggs’ tools of trade.

Biggs’ situation improved enough that by 1862 an ad had been placed for his newest barbershop. It would be a smaller operation without baths and at least ostensibly focused on tonsorial services. The ad placed his name most prominently over all other text. This curious decision signaled a shift in Biggs’ business strategy. It would no longer be on the quality of his services or the experience of a “New Orleans” style shaving parlor that people would flock to his chair. It would be on the basis of his established name and more than that, his identity as a Southern black man.

For Pete Biggs realized that with stiff competition in a time of civil war, he needed to sell his services on something that transcended skill or reputation. Something that would tie Los Angeles’ most prominent population base of white pro-Confederacy Southerners to his shop over all other competition.

Pete Biggs would sell his services based on politics and advertise himself as a pro-South and pro-Confederate black man.

PART VI

Walt Disney Productions released Song of the South in 1946. The movie today is remembered for two reasons: being the source of an obnoxious ear worm popularized by a now defunct ride and being the only Disney movie the studio refuses to acknowledge the existence of. The controversy around the movie’s idealized depiction of race relations and plantation life in the post-bellum South isn’t a recent phenomenon brought about by changing attitudes. The movie faced fierce criticism from black activists and organizations who regarded it as “an insult to the Negro people.” Even white critics like Manny Farber remarked that the movie’s black lead James Baskett was “so skillful in registering contentment that even the people who believe in the virtues of slavery are going to be impressed and want to know his secret.”

Above: James Baskett as Uncle Remus and Bobby Driscoll as neither Jim Hawkins nor Peter Pan

Though set in the years after slavery, the film’s critics saw in Song of the South the perpetuation of the Lost Cause narrative. In the aftermath of the Confederacy’s defeat, former Confederates immediately developed a counter-narrative to justify the actions that caused the war that devastated the South. This new narrative minimized the role of slavery in the founding of the Confederacy in favor of an emphasis on state’s rights. It characterized the conflict as a clash of civilizations between the honorable, chivalrous South who fought as gentlemen against the uncouth Northern hordes who disregarded military ethics and ravaged the land.

Most importantly, it characterized slavery as being an institution simply outdated at worst and benevolent at best. Lost Cause proponents claimed that slavery “elevated the African” and “bestowed upon him a sum of individual indulgences, which made him altogether the most striking type in the world of cheerfulness and contentment.” Had pesky Northern abolitionists not attempted to sow discord between North and South, the slaves would never have considered their condition to be one of oppression. Such a narrative was explicitly put into words by none other than former Confederate President Jefferson Davis in his book The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government where he wrote:

“Their strong local and personal attachment secured faithful service ... Never was there happier dependence of labor and capital on each other. The tempter came, like the serpent of Eden, and decoyed them with the magic word of "freedom" ... He put arms in their hands, and trained their humble but emotional natures to deeds of violence and bloodshed, and sent them out to devastate their benefactors.”

Despite the many personal narratives from former enslaved persons detailing the brutality and cruelty of slavery, the Lost Cause narrative persisted in a South fighting against Reconstruction and fighting to impose its own self-image into the world as the official truth. The idea of the honorable Southerner persisted in pop-cultural depictions of the Civil War throughout much of the early 20th century - most notoriously in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation - as did the idea of the servile slave content with his bondage.

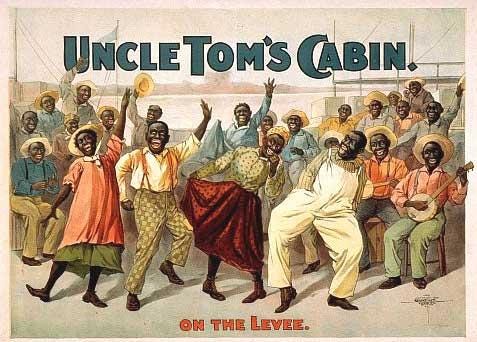

This myth of the Happy Slave became personified in the Tom Caricature. Ironically, the roots of this caricature - the dependable black male servant who never resists his white oppressors even in the face of unspeakable abuse - lie in a piece of antislavery literature that scandalized the South upon publication. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin attacked the institution of slavery with a title character who represented the ideal example of Christian renunciation, a man more moral than the cruel whites who ultimately take his life. But Uncle Tom was hardly a three-dimensional character, existing as little more than a literary device at the hands of a white author and lacking any depth or deeper motivation than apparent Christlike qualities.

Weak copyright laws soon meant that theatrical adaptations of Stowe’s texts were staged without her approval or control. If Uncle Tom under Stowe’s hand was a naively misguided character, then Uncle Tom on stage was an atrocious caricature rooted not in the ideology of the text as much as in the tradition of blackface minstrel shows. Tom was rewritten into a buffoon, a racist stereotype completely subservient to his masters and lacking any resilience of spirit. The Tom plays also downplayed or otherwise removed references to the violence of slavery.

Above: A poster for a blackface minstrel production of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Not surprisingly, Stowe’s character has rarely been warmly received by black readers since his inception. The phrase “Uncle Tom” became a pejorative in the black community for a black man perceived as participating alongside whites in the oppression of the black people he has betrayed and abandoned in order to curry favor and gain some minor degree of privilege not afforded to other black people. The heated epithet has been used in contemporary politics and lodged at various men accused of being too passive towards the struggles of black Americans at best, and towards those supporting political policies seen as detrimental to black Americans at worst. In popular culture, the figure of the self-hating black man came full circle in the form of characters like Uncle Ruckus in The Boondocks or Stephen in Django Unchained. In other words, deconstructions of the very character who unwillingly lent his name to the archetype.

Pete Biggs’ apparent support for the South echoes the Happy Slave myth on the surface. But the extent of Pete Biggs’ sincerity as a Southern-sympathizing black man in Los Angeles is unclear. Biggs left no records of his personal thoughts behind. That he would have had any affection for the institution of slavery as a former slave himself seems unlikely. It’s possible he sympathized with emancipation but clung to a boot-strap belief that only those who could prove themselves enterprising “credits to their race” (in parlance of the time) be freed. It’s possible he simply held a cultural affection for the South that translated into a political support for the Confederacy despite the consequences a Confederate victory would have for his black brethren still in bondage.

Or perhaps Pete Biggs simply played the game he knew best, good business. He saw the writing on the wall, the fact that the Anglo population of Los Angeles remained majority Southern. Saw the fact that an influx of newer and more skillful barbers - including black barbers - would chip away at his business. Saw that the position of a black man in America and especially a black man surrounded by die-hard rebel sympathizers had become especially precarious and that he needed to secure his own physical and economic safety by any means he had available to him.

If his black pro-South stance was a bit, his commitment to it would have made Andy Kaufmann blush.

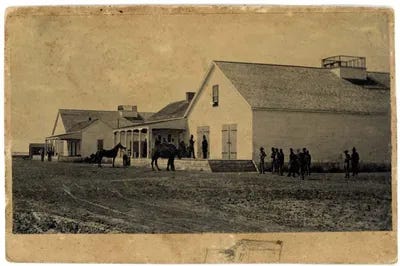

Less than a week after the surrender of the Confederate military, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Two days later on April 17th 1865, a group of white Southerners gathered to celebrate the murder of the US president. Biggs celebrated among them and led the crowd in a three-cheer chant for Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Biggs was arrested days later alongside seven other men and detained at the Drum Barracks fort.

Even in his own day, Biggs’ actions were met with confusion by white Unionists. The Daily Alta California wrote that the so-called “descendant of Ham” was “so impressionable” that “he has continuously been the vanguard of the secessionists and traitors of this place.” The irony of his imprisonment was surreal, former slave Biggs being relegated to a chain gain for supporting a government determined to die in order to maintain the institution that kept Biggs and millions of others in bondage.

Above: The Drum Barracks in Wilmington, California (now in the LA city limits and a history museum).

Biggs was among the last of the prisoners released in July 17th of 1865. A condition of his release was an oath of loyalty to the Union and to abide by and support all laws made during the war regarding emancipation. In other words, Biggs was freed on the condition of supporting the emancipation of others from the same situation he had been born into.

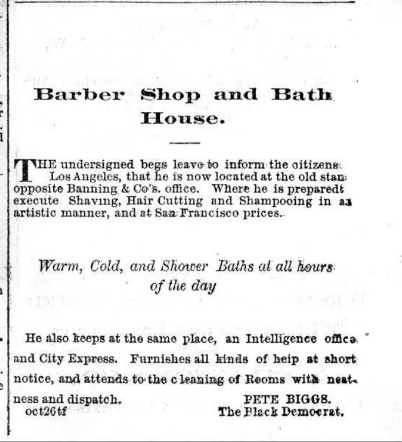

But Biggs continued to drop innuendos of his support for the Confederacy. An ad published in 1867 undersigned his name with a new title of the “Black Democrat.” At a time when the Democratic Party’s sympathies remained largely with the South, the real meaning of this self-description wouldn’t have been lost on any of Biggs’ current or potential customers. It screamed to those Southerners in Los Angeles “you’re safe with me.”

The odds against him, Biggs managed to hold onto his barbershop and a position of semi-privilege in Los Angeles whose history since California statehood had been marked by racial tension and violence. He survived the Civil War and the immediate Reconstruction years by navigating the political tensions between pro-Southerners and Unionists and he survived increased competition as Los Angeles expanded from a dusty pueblo of little more than a thousand to a small town with multi-level brick buildings.

Above: An advertisement for Pete Biggs’ barbershop. Note the undersigned title of “The Black Democrat.”

But he couldn’t survive Los Angeles. The town’s violence waned slightly since the opening of his barbershop and spiked as an influx of newcomers caused a fast boom at the close of the 1860s. Pete Biggs wouldn’t live to see the business he founded reach its twentieth year when he entered Baker’s Restaurant on May 5th, 1869. A Californio waiter named Victor “Sport” Lamorie engaged in a dispute with Biggs over what Biggs perceived to be rude behavior. Insults were flung. Dishes soon followed. Biggs and Lamorie began brawling when the waiter picked up a butcher’s knife and plunged it into the barber’s chest. Between forty-nine and fifty-four years of age when the knife pierced his heart, Pete Biggs died with his boots on in the City of Angels.

Victor Lamorie was arrested for the murder. As often happened in the days when Los Angeles boasted a weak and ineffective criminal justice system, he was acquitted by a jury of his peers. The jury consisted predominantly of Hispanic Californians who may have found more cause with a fellow hijo de pais than with a black man. Perhaps the race of the victim accounted for the lack of recorded attempts by a vigilance mob to storm the jail and lynch Lamorie, a common fate of murderers in Los Angeles at the time. Pete Biggs worked hard to carve out a position of economic privilege and respect in Los Angeles. But for all the work done in life, it could not secure him justice in death. Even in 1877, Lamorie freely walked the calles of Los Angeles “proudly conscious of having killed a distinguished character.”

But Pete Biggs was popular enough that his funeral attracted a large crowd. His daughter Juana and her newly-wed husband Nelson Smiley, himself a freedman, were among the attendants. Biggs left behind memories among frontier Angelenos but he didn’t leave behind a bloodline. His daughter died a year later, barely in her twenties. Her husband Smiley followed his departed wife a decade later in an alleged suicide.

Nor did the legacy of his memory or accomplishments survive the rapid changes and expansion that afflicted Los Angeles in the latter half of the 19th century. The model of excellence to the frontier town’s black community would be found in enterprising community leaders like Robert Owen and Biddy Mason, not in men who courted white approval like Pete Biggs. By the time Black LA grew in earnest along Central Avenue, Pete Biggs was a distant memory relegated to the records and history books and remembered only by those few old-timers clinging to life in the early 20th century.

But Pete Biggs remains an indispensable figure in the early history of American Los Angeles. A close examination of his life and the social context that created him paints a more complex picture than the “Black Democrat” image so easily and seductively reducible to Tom stereotypes. Biggs played the servant role as a professional barber but many instances in his life, from his flouting of racial norms at fandangos to his fatal fight, reveal a man unafraid of confrontation. That his habit to “occasionally become noisy and troublesome”, that his reputation as an “ornery cuss” wasn’t directed towards noble aims of advancing his community and instead directed towards his own self-advancement was unfortunate. Especially when his self-advancement hinged on him supporting the cause of maintaining a cruel institution he had the fortune to be released from years before so many millions of others.

Unfortunate, strange, confusing - but then again, when is history ever not?

Thanks Steve, what a character Pete Biggs sounds! Amazing article!