Bring Me The Head Of Joaquin Murrieta Part VIII: Ride Of The Rangers

The California Rangers chase Joaquin and chase their tails

If you ever want your perception of California to change, take a drive along the 5 freeway through the San Joaquin Valley.

Let’s say you’ve just left LA. You’re driving north out of the San Fernando Valley through Santa Clarita and Castaic. The rugged countryside seems carved by a cruel hand that prefers dust to flora. The freeway takes you higher and higher through hills cloaked in chaparral. You notice signs warning you to turn off your AC to avoid overheating while trekking up the steep incline. Signs for brake check stops for trucks abound. A few stall on the side of the road. The elevation peaks and decreases. The downgrade whips into a sudden sharp turn down a steep drop that blindsides you no matter how many times you’ve driven down the Tejon Pass and as your knuckles tighten around your steering wheel and you do all you can to avoid riding your breaks without slamming into the cars ahead, you drop like a roller coaster towards an empty stretch of valley with only cattle and waystation outlets to greet you as you exit southern California for the San Joaquin Valley.

Above: The San Joaquin Valley in a not-so-fertile time

Driving north along the 5, to your west the land rolls like ocean waves of grass. If the winter rains were generous, the color of the land is lush emerald. In drier years, the flaxen hills shine against the baking summer sun. To your east lies flat farmland covered in endless fields of almond trees or vineyards or whatever other crops farmers have forced into existence out of the increasingly parched soil with the combination of human ingenuity and human arrogance necessary to make the San Joaquin Valley the breadbasket of California and in turn to make California the bread basket of much of the United States. Large herds of cattle roam on dairy farms and the stench of livestock will penetrate your windows and occasionally seep in through the doors and windows of whatever waystation diner you’ve chosen to sit and take your meal in.

At times, the valley’s even elevation and abundance of rural farmland feels as if you’ve been dropped in Kansas or the Texas panhandle, an illusion broken only by the eventual appearance of the Sierra Nevada mountains to the east. But the farmland is a recent development born out of California’s agricultural transition from cattle ranching in the late 19th century. The San Joaquin Valley once hosted the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi before intensive agriculture drained Tulare Lake at the turn of the twentieth century. Mustangs, roaming descendents of Spanish horses run free, spread far across the valley for mesteneros to capture and tame while vaqueros drove cattle north and the US Army established a presence at Fort Miller near modern-day Fresno to bring Manifest Destiny to the Golden State’s interior.

In the San Joaquin Valley before the railway and before Miller-Lux engineered corporate ranching, before barbed wire fences and almond farms and oil derricks, a gang of outlaws could disappear from the men hunting them.

JUNE DOOM

With few proper leads, the California Rangers initially clung to Mariposa County with an eye towards capturing any horse thieves they could in the hopes of capturing Joaquin in their dragnet. In early June, Love reported one thief captured and some thirty-one horses recovered. In the middle of the month, they captured two more horse thieves and a man alleged to be a brother of Joaquin. No further leads were ever reported on this brother and the two prisoners were left dead on the road from bullet wounds. Love’s pattern of being incapable of returning live prisoners continued. William Howard was more blunt in the methodology of the Rangers: “When we were sure of a man being a bandit we shot him or hung him.”

The certainty of the animals the Rangers took being stolen and their prisoners being bandits is unclear. Love never specified to whom the livestock originally belonged. A critical report in the Daily Alta California inquired what Love and the Rangers did with the animals taken from “suspicious-looking strangers” with no clear answer. The prisoners’ pockets were remarkably empty for men who made their living from stealing. Maybe times were tough for rustlers. Maybe the California Rangers needed additional funds and figured no one would question a Mexican with an abundance of livestock being accused of theft and subsequently shot. Of certainty was that none of their efforts in June had turned up even a trace of Joaquin.

Evidence of Joaquin’s whereabouts was lacking. Rumors of his whereabouts were in frustrating abundance. A June edition of the San Francisco Herald quoted a letter from San Luis Obispo that claimed Joaquin had been dwelling on one of the local ranchos surrounded by fifteen to eighteen men. He had been allowed to stay there because he claimed that so long as he was allowed safe passage out of San Luis Obispo for Mexico, he would “do them no harm, commit no outrage.” An earlier May 4th report in the San Joaquin Republican claimed that Joaquin had been seen in San Luis Obispo ten days prior, meaning that Joaquin had allegedly been hiding in plain sight in SLO since April with no efforts made to capture him.

By mid-June, the papers exploded with rumors that Joaquin had arrived in Los Angeles on his southbound flight. The Los Angeles Star wrote that Joaquin’s presence in the county was “just as certain as anything else.” How certain this or anything else could be is unclear. Joaquin Murrieta the horse thief and brother-in-law of Reyes Feliz would have been a known sight among some in the pueblo. Angelenos and the local papers seemed convinced he and the Joaquin of Calaveras County were the same men, though this Joaquin made no apparent good on his promise to brutalize Ana Benites for her snitching to the Americans. But Angelenos nonetheless assumed Joaquin Murrieta rode in their midst again. By June 18th, reports from “men of veracity” claimed that Joaquin and his men were “now somewhere between San Juan Capistrano and San Diego, bound down to Lower California.”

Here’s where the reports become ridiculous: weeks before the June 18th edition of the Los Angeles Star, a group of horse thieves raided a settlement in San Diego County and then proceeded to rob the adobe of rancher Andre Ibarra near Mission San Luis Rey. The robbery sparked a posse against the bandits, who managed to maintain thirty-two of the forty horses robbed and who lost the trail of the large posse that included multiple Indian vaqueros mustered from the county who knew the land better than the Californios and Anglos. The identities of the robbers were never confirmed, but locals immediately believed the leader to be none other than Joaquin. By July 4th, the bandits were reported as having crossed the border after a raid on a rancho.

According to the Los Angeles papers, Joaquin was in Los Angeles until June 18th. According to local rumors, he was responsible for the robbery of Andre Ibarra’s rancho on June 9th. Was Joaquin racing up and down the coast on an almost ninety mile ride that whole month?

If Joaquin had in fact found shelter in Mexico, he didn’t remain.The Alta California reported that Joaquin had been tracked by a Santa Barbara posse to a location near to Los Angeles on July 10th. Then on the 13th he was said to be in Santa Barbara again. If the reporting was accurate, Joaquin zig-zagged up and down California with ridiculous haste and no apparent end goal. The Joaquin of Calaveras County moved fast but he moved fast across a single small county through wooded mountain trails. The Joaquin of Southern California, possibly Murrieta or possibly a nobody, seemed to fly across a hundred miles back-and-forth from Los Angeles to the border, while still managing to sneak back into Santa Barbara.

Such reporting stoked the skepticism of the Spanish-language column of the Star, El Clamor Publico. While critical of Joaquin and suggesting to their readership that he ought not be treated as a martyr of Anglo persecution, the paper doubted the possibility that every crime attributed to Joaquin could have all been the same gang’s work. Almost certainly it was nonsensical for a man who fled to the safety of Baja California to ride back into America in order to continue a pattern of thievery.

The reporting of Joaquin as an unstoppable force of Mexican banditry fleeing to the shelter of his home country did little more than serve a thinly-veiled propagandistic purpose. As one letter to the Alta California wrote:

“It is the general opinion that the banditti known as Joaquín’s gang, and other robbing parties, can only be exterminated by carrying the war into the enemy’s country, Lower California. An expedition of 60 men could easily conquer the whole peninsula, capture San Tomás and hang every bandit therein.”

That same summer an American named William Walker arrived in San Francisco from Mexico, defeated but determined. His business in Mexico had been to seek a grant to found an American colony in the state of Sonora. His stated reason that the Americans could do the dirty work of protecting the Mexican frontier from Indian raids. His unstated reason was the survival of slavery. The limitations imposed on slavery’s westward expansion and the growing influence of abolitionist factions represented a threat to the pro-slavery southerners. For many, the only solution was to expand Manifest Destiny south into Mexico. Walker began recruiting Californians for a filibuster expedition into Mexico. Their targets would be Baja California and Sonora.

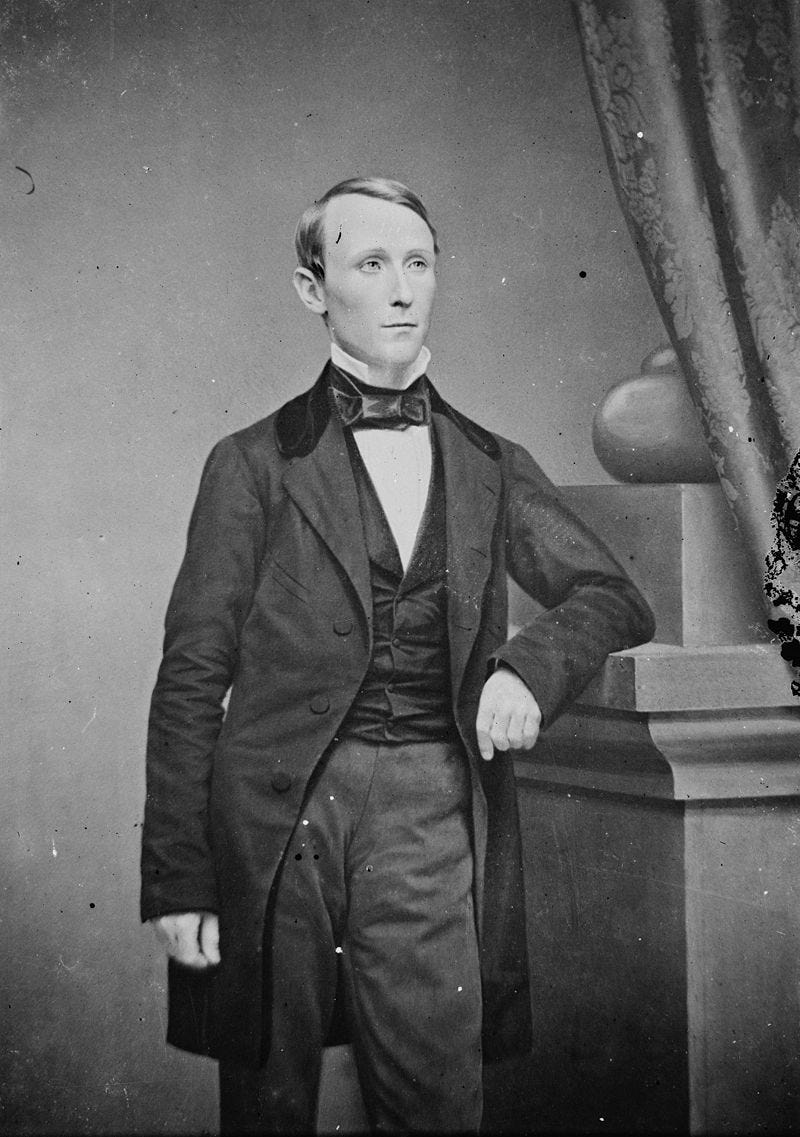

Above: Filibuster William Walker, who lobbied for an invasion of Mexico while California panicked over Joaquin.

Joaquin’s legend carried rumors that he was no mere bandit, but a guerilla leader with a network of followers from San Francisco to Ensenada who would upend the Anglo order at a snap of his fingers. The rumors were patently false. But the added terror of a Mexican uprising proved to be the best PR that Walker could have hoped for.

OH BROTHER-IN-LAW, WHERE ART THOU?

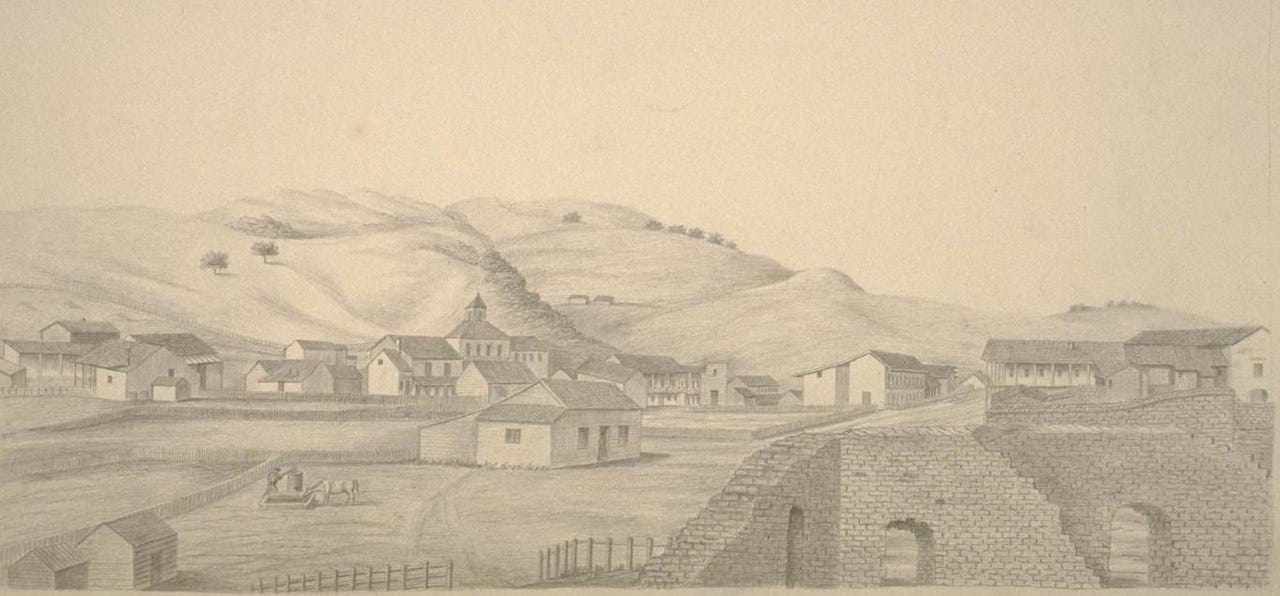

News traveled slowly in California. The Rangers wouldn’t have been aware of the rumors that Joaquin was Mexico-bound until well after the fact. When Mariposa failed to turn Joaquin up, Love cut west across the scorching San Joaquin Valley to the coast in a hard two day ride that landed him in San Juan Bautista on July 12th of 1853. San Juan Bautista was an old mission community with a primarily Spanish-speaking demographic. Love’s new strategy appeared to be to flush out the Hispanic communities for information on Joaquin’s whereabouts and to scour the coastal ranges where a man could easily disappear from the law. Whether through leads or luck, his arrival in San Juan Bautista paid off instantly.

Above: San Juan Bautista, CA, circa 1856. Not pictured: Kim Novak falling to her doom while Jimmy Stewart looks on. Twice in one movie.

According to one of the regular reports Love wrote Governor John Bigler to maintain the governor’s faith in the rag-tag militia, Love and the California Rangers had located none other than Joaquin Murrieta’s brother-in-law and the last of the Feliz brothers, Jesus Feliz:

“He says he will take and show us to Joaquin if we will release him. I will try him for a while to see what it will end in. There appears to be quite a number of horse thieves hid in the mountains back of this place between here and the Tulare Valley. I hope I may make him useful to me in hunting them out.”

Love never specified if the youngest Feliz was involved in banditry as well. How Jesus could have possibly known the whereabouts of an ever-transient brother-in-law is unclear. He never signed a later affidavit and he never gave public confirmation of his own role in Joaquin Murrieta’s passing. If Jesus had any useful information, it led the California Rangers up and down the coastal ranges for the next eight days. Where he apparently didn’t lead them was where Joaquin was next reported to have been seen, in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles County.

The bulk of the valley encompassed the vast landholding of Rancho ex-Mission San Fernando. The land was divided between two owners, a Spaniard named Eulogio de Celis and a California named Andres Pico. Pico was the brother of former governor Pio Pico, a prominent citizen who once commanded a unit of lanceros in the Battle of San Pasqual and who negotiated the terms of the Treaty of Cahuenga. Acquiring a half-interest in Rancho ex-Mission San Fernando, he oversaw the valley south of contemporary Roscoe Boulevard towards the Santa Monica Mountains. Allegedly fleeing Los Angeles law, Joaquin and his men attempted to steal forty horses on their exit out of the valley.

He and his men didn’t ride far before Pico’s vaqueros routed them. Instead of attacking the thieves, the vaqueros granted the men a warning. Thieving from a Pico, one of the most powerful families in California, would be an instant death sentence. Joaquin returned the horses but kept those he and his men needed to escape. If the reports were accurate and this was Joaquin Murrieta, he had learned the hard lesson of his brother-in-law Claudio Feliz’s fatal mistake: never rob from the rich.

DEADLINE

Years later, William Howard would claim that the reports of Joaquin’s whereabouts in Los Angeles would steer the Rangers south into Los Angeles and then back into the San Joaquin Valley through the Tejon Pass. Cinematic as the image of twenty Rangers barrelling down the precipitous mountain road is, Love never recorded a visit to Los Angeles. The itinerary is as unlikely as Joaquin’s given that San Juan Bautista is some three-hundred miles north of Los Angeles and requires multiple mountain passes. To double back after the strenuous ride would have resulted in mutiny. According to Love, the men were already close as it was. They had ridden a month and a half with minimal results and their $150 a month stipend barely covered the cost of their venture.

As recorded by Love, the actual trail of the Rangers clung close to the coastal ranges from July 12th until July 20th when they approached the Panoche Pass towards Arroyo Cantua, a canyon creek that cut through the mountains into the San Joaquin Valley. They came across a large remuda of seven-hundred horses driven by a team of seventy Mexican wranglers and curiously accompanied by sixteen women. The odds against them, Love and the Rangers rode into the Mexican camp the following dawn. The Mexicans insisted they were mesteñeros capturing the mustangs that still roamed the San Joaquin Valley. Love doubted their claim, but found only eight branded horses, all with Spanish brands. Love took a few horses he claimed to recognize with no fight from the mesteneros. If he had deeper suspicions of the men, he was uncharacteristically restrained in his dealings with them. Given the fifty-man advantage that the mesteñeros had on him, the restraint was wise.

Above: The hills of the coastal ranges near the edge of the valley, not far from where the California Rangers would find their prey…

His wisdom may have been mistaken. Love and the Rangers camped in the canyon ten miles back to watch the behavior of the mesteñeros. For two days, the mesteñeros continued to water and graze the horses. At dawn on the 24th, they found the camp deserted. The mesteñeros had stolen away in the night without notice by the Rangers. The frustrating turn of events forced the Rangers deeper into the canyon to follow any tracks before the heat and exhaustion forced the men to stop.

The men’s contracts as California Rangers would end in a week. Their $150 stipend would vanish with it and they hadn’t even spotted Joaquin. Their best possible lead slipped from their fingers right at the tail end of their expedition. The mood of the men must have been heated and it forced Love into a corner as he was unsure if he could find Joaquin or even hold his men together before the month was up.

What sort of discussions did Love have with his men in the midst of their stalemate? Did he reassure them that the bandidos were a stone’s throw away and all they required was the continued faith in his leadership to see their hunt to its end? Was he regretfully honest in informing them that their white whale had vanished for distant waters? Or did he begin to confide his trust in only a few of his Rangers, those most loyal who he held council with while shutting out the doubters? Did Bill Byrnes, who for reasons unknown never claimed to know Joaquin until after his killing finally confess that he could identify him on sight? If so, what could compel him to finally reveal the information?

Whatever decaying camaraderie affected the disillusioned Rangers, they rose at witching hour on the 25th towards the mouth of the canyon at the gates of the San Joaquin Valley with no sign of the band. But against the red sunlight that rose above the distant Sierra Nevadas, the clear horizon was stained with a small plume of smoke that rose from the valley. After weeks of lonely hunting, dirty, desperate, and hungry, they had finally found their prey…

Coming Next: The California Rangers make their fateful encounter that ends the hunt for Joaquin and begins a long legend that persists through history in Bring Me The Head Of Joaquin Murrieta Part IX: Estoy Muerto!