Bring Me The Head of Joaquin Murrieta Part VII: A Man Called Love

California selects its man to hunt Joaquin

"Sure, we're criminals", you said. "We've always been criminals. We have to be criminals". -Frank Miller

Philemon T. Herbert was a hot-headed Alabaman who became a hot-headed Californian. His chief claim to infamy was killing an Irish waiter who refused to serve him breakfast past 10:30 AM. Needless to say he was not a friend to Irishmen or customer service employees. But before he gained infamy through killing waiters for their strict adherence to kitchen schedules, the Mariposa County state representative was the loudest advocate for state action against the Joaquin gang. His solution was to raise funds in the budget for a five-thousand dollar reward for any man or party who captured or killed Joaquin.

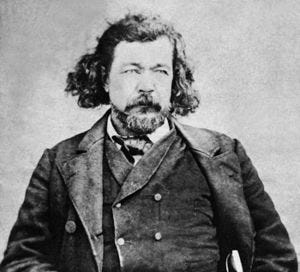

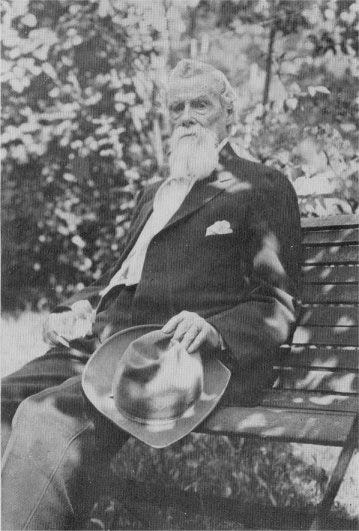

Above: Jose Maria Covarrubias, opponent of the California Rangers legislation

The proposal was not instantly popular. The chief opponent of the bounty was a French-born Californio named Jose Maria Covarrubias, who had served as a secretary for Pio Pico during his tenure as governor of California. Covarrubias was under no illusion of how the threat of Mexican banditry and the fear of a Mexican uprising stoked passionate terror in Americans. He feared that Anglo anger would cause their wrath to be diverted from the true culprits and towards any random Hispanic they suspected of banditry. His objections carried additional ethical considerations on whether offering such a large bounty would draw out the most morally righteous men with an actual eye towards justice or whether it would “tempt unscrupulous and unprincipled men to palm off, by purchased evidence, the head of another for that of Joaquin.”

His warnings went unheeded. A proposal to authorize the organization of a company of “twenty or twenty-five good horsemen” to capture or kill Joaquin gained 127 signatures. Most of those who signed expected the proposed militia to rid the entire countryside of Mexican banditi beyond Joaquin and his gang. A similar proposal landed on the desk of Governor John Bigler. Signed by 100 men, it demanded the mustering of a ranger company to hunt down and flush out all bandits in the state.

Popular support for a ranger unit mounted. Herbert presented a bill on May 10, 1853 for the creation of a twenty-man ranger division that would serve for a period of three months and with each man salaried at $150 per month. The express purpose of the rangers was to capture the gang of robbers commanded by the so-called “Five Joaquins.” Missing from the proposal was the initial five-thousand dollar reward Herbert had proposed. The three-month limit served to quell any objections over the accrued expenses involved in maintaining a permanent law enforcement agency.

The bill was killed 21-17. State legislators were still skeptical of funding a manhunt that could at best be a wild goose chase and at worst inflame the anger of Californios due to the expected excesses of American bounty hunters in hunting Mexican bandits. Reports on who exactly Joaquin had been so vague as to be useless to anyone actually attempting to hunt him down. Was he a twenty-three year old Sonoran horse thief? A thirty-something Mexican guerilla who fought in the war? Did he have black hair? Did he have brown hair? Was he dark? Was he fair? Was he handsome? Was he ugly?

Undeterred by their opponents, Herbert and fellow supporters of the bill attempted to force it through during an evening session. It was pure political manipulation since they knew nobody would attend an evening session, but it worked. The bill passed the state congress and was bound for the governor’s desk. On May 17th, Governor John Bigler approved the formation of the California Rangers, in addition to the original $1000 reward he had offered in February.

But who would lead the twenty-man company? Herbert’s initial proposal incidentally came with a high recommendation already in place. He suggested a man with years of experience in the wilderness. A veteran of the Mexican-American War who had braved the far reaches of the borderland frontiers. A man who had already proved his mettle as a law officer in the state. A man who had already brushed shoulders with a confederate of at least one of the “Five Joaquins” and had brought him to justice, dead on arrival.

To captain the California Rangers, Herbert and Mariposa County residents believed there was no more natural candidate than Harry Love.

THE MAN FROM RIO GRANDE

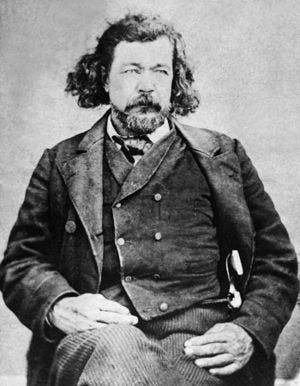

Above: Artist’s rendering of Harry Love

Vermont is an anomalous state. It is second to Wyoming as the least-populated state in the union but it is the sixth-smallest state, no vast cut of countryside like the land of cowboys and Chris LeDoux. It sits on the east coast, but is entirely landlocked. Geographically, it is situated close to the core of the United States. Culturally, it is not dissimilar from a frontier territory. Like Wyoming, Vermont hopped on women’s suffrage early, granting women the vote in 1880. It beat California as being the first state to grant both civil unions and same-sex marriage legality and did so without outside pressure. The sparse population and sense of isolation no doubt plays a part in Vermont’s hinterland vibe. Throw a rock at any given point and you’re more liable to hit a tree than you are to hit another human being.

Perhaps the landlocked isolation is what drove Vermont native Harry Love to the ocean when he fled home as a teenager. Or perhaps it was simply that the life of a sailor was one of the few avenues open to a young man seeking freedom from his family. Love was born in 1810. His mother died when he was a young boy and his father would remarry on the cusp of his adolescence. For reasons unclear beyond the natural affections of a man towards the woman who birthed and nursed him, he felt nothing but contempt for the woman his father married in her place. By age fifteen, he called the sea his new mother as so many landless renegade men have done in history. It wouldn’t be the last time he sought out a surrogate mother, but his nautical mother would prove less fatal than future women in his life.

Love’s seafaring career lasted into his thirties, long enough for him to make the voyage around Cape Horn to California at age 29. For a young man from the woods of Vermont, the coastal cliffs and wide spaces of ranchland must have made an impression on Love. It didn’t impress him enough to keep him on the shores of California, but by then he had grown tired of sailing. He left the sea and tried his hand at cowboying in Texas. When the war broke out between the US and Mexico, Love worked as a longshoreman in Mobile, Alabama. Fired up with patriotic zeal and a desire for new adventures, Love promptly joined a company of Alabama volunteers due for the Texas-Mexico border. Love was far from youthful when he enlisted, but the six-foot two grizzly of a man was in prime enough health to scout along the Rio Grande during the war. His hardiness saved him from the more natural hazards of being far from home in a foreign land and substandard conditions. Of the 15,000 troops who would be camped with him in the Chihuahuan city of Camargo, 1,500 died of dysentery.

The war’s end didn’t close Love’s military career. Captain William Chapman hired Love as an express rider to deliver messages to the various forts scattered along the Rio Grande countryside from his base of Fort Brown in Matamoros. The route took him through inhospitable arid desert and directly in the territory of Indian nations at war with the US. He and his fellow riders found themselves frequently fighting against the tribes to complete their routes. Chapman’s wife Helen remarked in one 1849 letter her astonishment to see Love return bearing dispatches after it was rumored that he had been murdered. His maritime background and experiences on the Texas borderlands made him the first US Army expedition up the Rio Grande from Matamoros. Love captained a keelboat up the river and though the expedition ended a hundred and fifty miles south of El Paso and didn’t extend the full length of the Rio Grande into Colorado, it brought American interests farther into Texas than most had ever dared to travel. Given the somewhat unforgiving desolation of West Texas, one wonders if the Army felt buyer’s remorse when they laid eyes on it.

Above: Rio Grande near Big Bend in Texas

Love’s eyes had already turned farther west than El Paso, towards the territory he laid eyes on ten years prior. Ever the transient, Love saw opportunity in the Gold Rush and took it. Venturing from Texas across Mexico, he hopped a steamer in Sinaloa and arrived in San Francisco at the end of 1850. Typical of most newcomers, he was unsuccessful as a gold miner. He worked as a carpenter by trade and soon recognized that his scouting and fighting experience made him a valuable asset to a state struggling to maintain some semblance of civility. He took a position as a deputy sheriff in Santa Barbara and later pursued the killers of Allen B. Ruddle, among them allegedly Pedro Gonzalez, a member of Joaquin Murrieta’s gang.

The remaining photographs of Harry Love depict a burly man with long black curls and an unkempt face, his piercing blue eyes glaring in perpetual annoyance. Resembling some barbarian or buccaneer out of time, he cut an impressive figure to those who loved him and seemed “more like a large-sized ape than a man” to those who considered him an “illiterate and a coward.” Hubert Howe Bancroft’s unreliable history best described Love as a “law-abiding desperado.” Like many law officers throughout history, Love straddled the line between civil servant and hired thug. To those critical of him, the distinction was made only by the badge he wore. It was a distinction he was unburdened with, just as bounty hunter Tom Horn was unburdened with it, just as the notorious Rampart CRASH division of the LAPD was unburdened with it. “Any Means Necessary” was a motto that would have greatly appealed to a man like Harry Love.

The Five Joaquins

The legislative act signed by Governor Bigler on May 17th, 1853 read as follows:

Captain Harry S. Love is hereby authorized and empowered to raise a Company of Mounted Rangers not to exceed twenty men and muster them into the service of the State for the period of three months, unless sooner disbanded by order of the Governor, for the purpose of capturing the party or gang of robbers commanded by the five Joaquins, whose names are Joaquin Muriati, Joaquin Ocomorenia, Joaquin Valenzuela, Joaquin Botelier, and Joaquin Carillo, and their banded associates.

The notion of “Five Joaquins” earned a mythic status in the Joaquin legend. But there’s no indication after the fact that the gang responsible for the Calaveras County robberies was ever led by five men all named Joaquin. Likely the state gathered what evidence they could based on known thieves named Joaquin and threw spaghetti at the wall to see which Joaquin they could catch. Five names on the act. One a misspelling of “Joaquin Murrieta”, the horse thief named by Reyes Feliz the year prior. One the mysterious “Joaquin Carillo” named in the initial bounty who has disappeared in history beyond being an alleged stepbrother of Murrieta through his mother’s marriage to a Carillo. The other three men’s fates were entwined in bizarre ways, the blank spots filled with rumors unsubstantiated by tellers of tall tales and the libel of lynch mobs.

BOTTLES

Joaquin Botellier was a misspelling of a man known as Joaquin Botellas. Little concrete knowledge exists except that according to testimonies collected by Frank Latta, he escaped the fate of the more infamous Joaquin by remaining hidden in Monterey. Afterwards, he disappeared from any verifiable public record.

LOS HERMANOS

Joaquin Ocomorenia and Joaquin Valenzuela were brothers. Ocomorenia’s birth name was Jesus Valenzeula. According to Frank Latta’s extensive but flawed Joaquin Murrieta and his Horse Gangs, Valenzuela was a member of Joaquin’s gang, a fellow Sonoran who followed gold fever to California and had similarly fallen into banditry. He was allegedly killed during the final confrontation between the California Rangers and buried by surviving gang members when they returned to bury the dead.

His brother Jesus Valenzuela took his brother’s name and added as a surname an old pseudonym from youth, Ocho Moreno, Anglicized as Ocomorenia. The claim that he took the name “Joaquin” in tribute to a fallen brother is complicated by the fact that he was named in the act two months before his alleged brother’s alleged death. Presumably Governor Bigler was a clairvoyant. Whatever the case, Ocomorenia became an associate of Irish-American outlaw Jack Powers. The Irishman led a colorful life in California worthy of its own post. He had been a member of the Hounds in San Francisco before being driven from the city into gold country. Following the loss of his ranch land after a long legal battle, he ran afoul of vigilantes after hiding a judge named Ned McGowan, who fled San Francisco to avoid the wrath of the Know-Nothing Party members who accused him of supplying a murder weapon to a recently lynched killer. McGowan wrote enthusiastically of Powers’ role in his escape. It was meant as praise, but merely served to smear his name. Powers soon found himself in Los Angeles accused of running a burglary ring, then jumped bail after an arrest in the City of Angels.

In May 1858, Powers’ name finally entered the paper for positive news, a record setting horse race of 150 miles, which he rode in a mere six hours with the aid of a twenty-four mustang remuda. The fame soured to infamy. An outlaw named Jose Antonio Garcia was captured by San Luis Obispo vigilantes and his confession named Jack Powers as one of the many members of a bandit gang associated with Pio Linares. The vigilantes who remembered his infamous role in hiding McGowan and his flight from the Los Angeles law fingered Powers as the secret leader of the gang and the names mentioned by Garcia were added to a reward posting. Powers managed to flee the state for Mexico. Joaquin Ocomorenia was less lucky.

On June 3rd of 1858, the Daily Alta California reported that a Joaquin Valenzuela, AKA Ocomorenia, was tried and hung by a vigilance committee in San Luis Obispo. The charges listed were “murder, rape, and kidnapping an American child on the Merced River.” Vigilante Walter Murray claimed in a letter to the San Francisco Bulletin that Valenzuela had “died acknowledging his guilt, asking pardon of his friends, and warning all malefactors not to tell their secrets, even to their own countrymen. "asi se pierde" said he — that is: "Thus you lose yourself."

Like many lynchings of Hispanic men in California, the circumstances were suspect to others in the Spanish-speaking community. The Los Angeles-based El Clamor Publico attacked the SLO vigilance committee for executing an innocent man and relied on the testimony of a rancher named David Alexander, supposedly an employer of Valenzuela. Murray was indignant over the defense of the man he helped lynch. It was in his open response to El Clamor Publico that he claimed Valenzuela was the very Ocomorenia who rode with Joaquin Murrieta, a claim made merely off the 1853 Ranger Act. Murray would continue to list a variety of charges against Valenzuela/Ocomorenia, from kidnapping an Anglo girl and grooming her to “hate the gringos” to killing the kidnapped girl’s father to the theft of horses alongside Jack Powers. Murray’s claims are unsubstantiated beyond the confessions of other hanged men and various witnesses. Of certainty was that Jesus Valenzuela/Joaquin Ocomorenia had met his end five years after the mustering of the California Rangers originally tasked to bring him and the other alleged four Joaquins in.

EL CABALLERO

The decision to initially brand the Joaquin of Calaveras County “Joaquin Carillo” makes retrospective sense when one considers Joaquin Murrieta’s bond to a Carillo family in Sonora. It’s possible this connection was made by those who offered the surname to the Governor. It’s possible the Joaquin of the gold fields really was a Carillo and not Murrieta. But it is also likely that, in choosing the surname Carillo, Anglos were settling an unsettled score with a Californio who they felt had escaped justice.

The Carrillo family of California comprises a massive dynasty with descendants remaining to this day. The Carrillo family provided California its politicians, including a governor and the mayors of Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. Even Hollywood was touched by the Carrillo family when Leo Carrillo, a descendent of explorer and soldier Jose Raimundo Carrillo, played Cisco Kid’s sidekick Pancho on TV.

Less prominent was an actual Joaquin Carrillo of San Diego, or his son Jose Ramon Carrillo. Ramon was born in 1820, ten years before Joaquin Murrieta. When his father died, sixteen year old Ramon relocated with his mother to a family plot near Sonoma. Ramon was a natural equestrian who worked as a mayordomo del campo, range boss, of his family’s land. He was by all accounts the spitting image of an idealized Californio horseman, with a stature that only increased when he gained fame for single-handedly killing a grizzly bear. His sense of daring and patriotism led him into the military to defend California from the Yanqui invaders and he joined up with a band of men led by the San Francisco alcalde Juan Padilla.

His tenure in the militia would be the event that would stain his reputation. In June 1846, two Bear Flaggers named Thomas Cowie and George Fowler were found murdered. Evidence suggested the men had been dragged around by a reata and tortured before their deaths. Suspicion fell on the Juan Padilla band and eventually to Ramon Carrillo himself. Carrillo found himself defending his innocence after the war, by which point he had migrated back to Southern California after a tenure with the Mexican military that saw him participate in the Battle of San Pasqual. His warring in Southern California saw him in the ironic position of protecting American prisoners of war from execution. His act of clemency did little to repair his reputation among Americans who still believed him responsible for the deaths of the two Bear Flaggers.

Jose Ramon Carrillo remained in Southern California and married the wealthy widow Doña Vicenta Sepulveda de Yorba. The marriage granted him joint ownership of a plot of land in present-day Norco and eventually land adjacent to Juan Jose Warner’s ranch near San Diego. Ramon’s reputation as a chivalric caballero combined with the accusations around him fostered rumors that he was a secret bandit chief. Some claimed he was even the true Joaquin Carrillo who rode with Murrieta. Almost no evidence suggests it. Ramon remained in Southern California as a rancher until 1864, when he was murdered by an unknown assailant under the suspicion that he had been the murderer of American rancher John Rains. With his dying breath, Ramon challenged the Devil himself to a duel should he be resigned to Hell and maintained innocence of every murder he had ever been accused of.

Five names given to the Rangers. Considering the vague descriptions of the men in question and the inconsistent reporting as to Joaquin’s whereabouts, one wonders whether or not the Rangers were entirely aware of what their duties were. Very little evidence pointed to any of the men as being involved in the robberies beyond hearsay. Joaquin left no trail beyond his alleged visit to Pacheco’s rancho. The generic physical appearance provided by Bigler could have applied to hundreds of Hispanic vaqueros employed across the state. Consider the frequency with which men are racially profiled today. Now consider the fact that no photograph of Joaquin nor means of distributing photographs to every law officer in the state existed. Covarrubias, naysayed by Anglos for his objection to the creation of the California Rangers, had every reason to fear that the twenty men would simply capture or kill the first suspicious Mexican they saw.

CALL TO ARMS

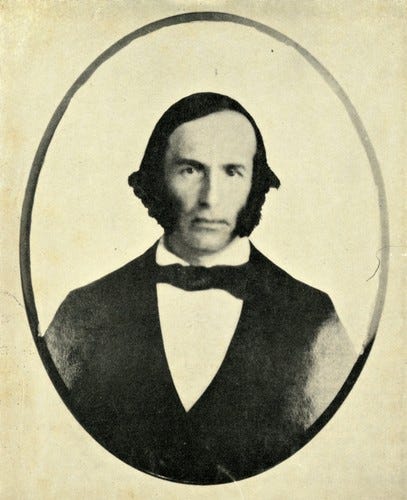

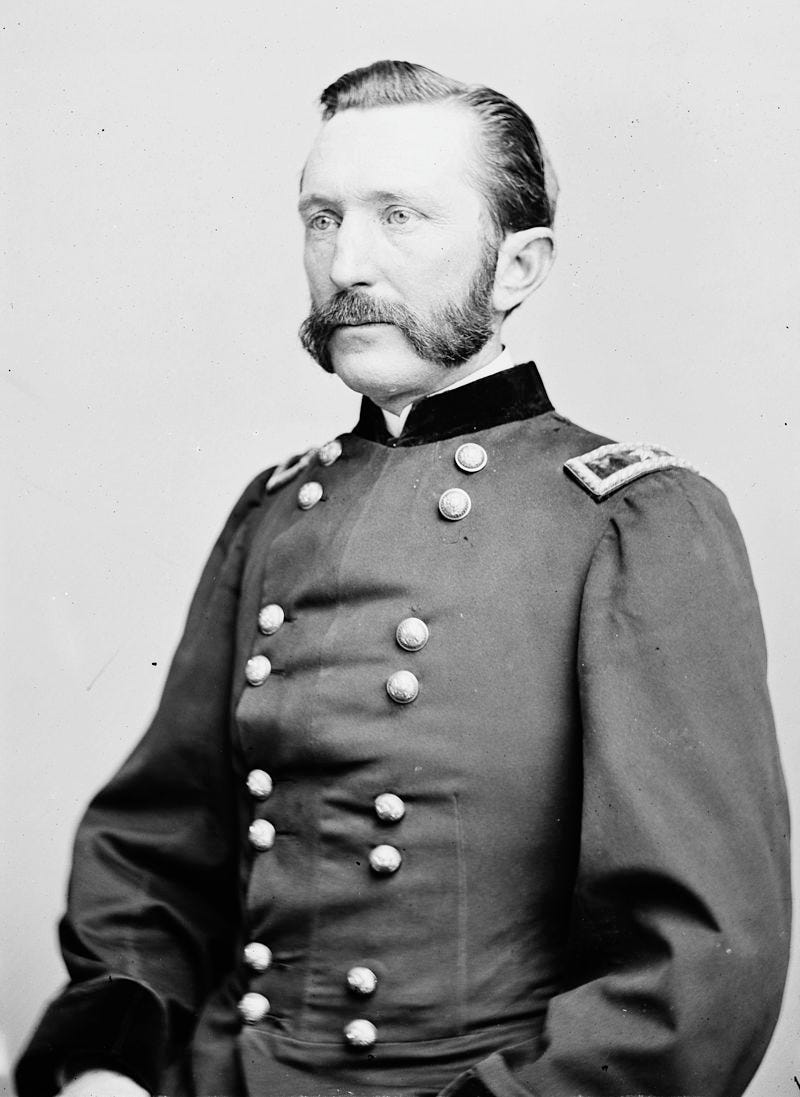

Above: William J. Howard towards the end of his life.

William J. Howard came to California to flee a broken heart. He was born to a Virginian planter family who relocated first to Mississippi and then later to the Republic of Texas. His biography details a privileged childhood learning to hunt alligators in the swamps of Washington County near his family’s plantation. Howard never questioned the ethics of slavery. He likely justified his family’s role in the horror by suggesting that they had been “ethical” slave owners. This insulated worldview was shattered when he came upon the horrific scene of a white mob decapitating a black man in the streets of Galveston. One of the only other disturbed white onlookers was a teenaged girl named Eliza. He rushed to comfort her. The two became smitten. As with first loves, theirs faded fast. Stinging from a single rejection after a dance, he informed her that he would leave Texas for San Francisco.

California proved quickly inhospitable to the young man. Texans had a reputation in California as desperados and he was nearly killed during a fight. Howard would claim to flee the wrath of hair-trigger tempered prospectors for the hospitality of mountain-dwelling Indians. How true this Dances With Wolves fantasy is depends on one’s willingness to take the tall tales of a frontiersmen at his word. Almost certainly he purchased land in Mariposa County where he established first a mule train service, and then later his own ranch outside of Hornitos. The countryside lined with live oak bore a passing resemblance to Texan cattle country and proved ideal for raising horses.

Above: Mariposa County countryside, where Howard would have ranched and raised horses.

Howard was a reputed crack shot with a rifle, fluent in Spanish and certain indigenous languages, who allegedly operated something of a detective service from his ranch. These qualities combined with a hardiness that saw him survive attacks on his life from drunken forty-niners made him a natural candidate for the California Rangers. Harry Love traveled to the twenty-six year old Texan’s ranch in Mariposa County and tasked him with the legwork of recruiting the remaining men necessary to fill out the new ranger unit. Love told Howard “you are more familiar with the fighting men of this part of the country” and Howard sought able men already hardened by fighting Indians and Mexicans. Howard’s social connections as a rancher made him an apt recruiter, but like many frontiersmen, his personal accounts were frequently stained by self-serving fabulist embellishments. In his later years, he would claim to have personally known the wife of Joaquin Murrieta and to have engaged in a shooting contest with her. Which he of course conveniently won.

An examination of the list published in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1907 reveals a brief sketch of the lives of the men who called themselves the California Rangers. In some respects, the list represents a microcosm of the men who fought in Mexico before migrating to California during the Gold Rush. Many of the men would migrate outside the state for greener pastures when their fortunes failed them. Of the twenty men enlisted, seven would be murdered and only one would live to an exceptionally old age.

Above: Transcription of the muster roll for the California Rangers, published in the San Francisco Chronicle. Biographical details added.

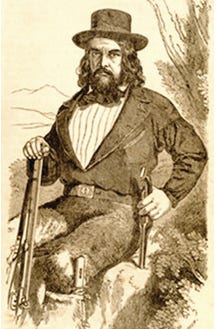

Patrick Edward Connor was one of the first hired on. Connor was born in County Kerry, Ireland on Saint Patrick’s Day. Ten years Love’s junior, he emigrated to the US at nineteen, making him among the generation of Irishmen to arrive before the Famine created a mass exodus from Eire to America. He almost instantly enlisted in the US Army and served in the Second Seminole War as a dragoon. After his discharge in 1844, he moved to Texas and became a naturalized citizen concurrent to Texas’ annexation into the US. He re-entered military life during the Mexican-American war and served as lieutenant in the Texas Volunteer unit. He left the war as a captain, honorably discharged after bouts of joint pain following a wound sustained at the Battle of Buena Vista. He followed gold fever to California and nearly survived drowning when the small vessel he sailed on was overtaken by heavy surf on the Pacific coast. Given his experience, he was naturally signed on as Love’s lieutenant to help lead the Rangers.

Above: Patrick Edward Connor

The other nineteen men’s careers may not have been as immediately distinguished, but each of them lacked nothing in skill and savagery. Such was the case with Tennessean William T. Henderson. Compared to the six-two Love, Henderson’s five-eight frame was immediately less imposing. Like many smaller men, he made up for it with reckless energy and ruthlessness. One account claimed he hung a man single-handedly and yanked on the end of the rope like a bell pull, pulling all of his weight into it until the hanged man’s hempen jig ended.

Among the recruits was none other than Bill Byrnes. Following his escape to San Bernardino, Byrnes settled in Hangtown (modern-day Placerville) where he occasionally prospected for gold. If his goal had been to hang up his guns, he chose the wrong state. Byrnes participated in the El Dorado Indian Wars of 1850 and 1851, costly and bloody expeditions to retaliate against indigenous retaliation against unprovoked attacks by forty-niners on the local natives. Regarded as a crack shot and a tough man, he caught the eye of Kentucky native and general James Madison Estill. Estill was a friend of Don Mariano Vallejo who carved out a livelihood of selling beef to California Indians and providing it to prisoners on the Waban, a 268-ton ship docked in the San Francisco Bay and fitted to hold thirty prisoners. Estill and others recognized the growing need for a proper prison in the new state, and from this need the first seeds for what would become San Quentin were planted. Estill saw in Byrnes a possible guard captain capable of maintaining the day-to-day operations of a penitentiary designed to hold California’s worst criminals and tested his resolve by hiring Byrnes to guide a wagon train from California into the Utah Territory.

Byrnes led the wagon expedition but the offer to join the California Rangers came before he could accept an offer to captain the guards at the growing prison. According to his daughter, Byrnes was torn about the prospect of killing an old friend. He was not apparently torn enough to decline the offer.

The twenty men called Howard’s ranch their base. Howard supplied horses from his remuda and the first $150 salary helped provide some of the supplies they needed. Muzzle-loading rifles and Colt Navy revolvers served as their primary firearms. All other supplies were sparse. They intended to travel light, with only a bedroll and the bare necessities for an individual mess kit consisting of a plate and a coffee cup where they would roast their coffee in the same cup they drank from. They mustered on May 28th in Quartzburg, the official beginning of their manhunt for the Joaquin gang.

The California Rangers faced an immediate complication to their mission beyond the fact that word on Joaquin’s whereabouts were sparse. They had an entire state to search for a man and his band, and only three months to find him. The decision to financially cap the California Rangers off had practical origins. Three years prior, the state had nearly bankrupted itself in a failed war against the Quechan. California was not capable of maintaining a militia costing $3000 a month (approximately $108,000 in today’s money) for an indefinite period. Nor was it prudent to keep a full-time militia with vague orders as “hunt a guy named Joaquin in a state full of them”, orders that could sour fast as Covarrubias had warned. The Calaveras County posses had failed to capture Joaquin when he was within an arm’s reach. Joaquin had vanished from the public eye and the California Rangers had the mountains, coasts, and valleys to scour in a span of a single summer.

Such practical concerns weren’t likely on Governor Bigler’s mind when he signed the act. Re-election was his long game. Pressure mounted on him and the state to quell the surge of Mexican banditry that haunted the public consciousness. Striking down the act would have been deeply unpopular, especially when the Democratic vote was threatened to be split by the pro-slavery faction. The murders the Joaquin gang committed required retribution. But the manner in which Bigler and Herbert chose to see justice carried out were borne out of little more than political expediency.

If Love had any doubts about the ability to capture Joaquin or any reservations regarding the identity of Joaquin, he never expressed it to Bigler or to his men. Why would he? $1000 plus the larger private rewards offered by the Chinese community was an opportunity that would have been foolish to decline on the basis of ethics or resources. Love was forty-three years old when he captained the California Rangers. He couldn’t continue fighting and sleeping under the stars while living an itinerant life forever. Time would catch up with him. When it did, better to be a landed man than still chasing outlaws for fortune.

When Bigler initially posted the thousand dollar reward, he had no expectation of a twenty-man force. $1000 split twenty ways netted each man a mere $50, just around $1800 today. With the monthly $150 stipend spent primarily towards surviving the following two months in the California wilderness, the twenty California Rangers anticipated their reward and expected it to be split evenly. The question at the time wasn’t whether Love would keep his word.

The question was whether they would find Joaquin before their time ran out…

Coming next: The California Rangers brave two stagnant months in the hellish heat of Central California while newspaper rumors report Joaquin’s southward ride in Bring Me The Head of Joaquin Murrieta Part VIII: Ride of the Rangers